Resilient Institutions: Learning from Canada’s COVID-19 Pandemic

Foreword

This report is a DIY project.

As the presidents of two organizations committed to better public policy and better government, we share a deep interest in what happened to our national institutions during COVID-19. During a pandemic-safe outdoor lunch in June 2022, we both noted there was no official effort to examine that key question on a pan-Canadian and public scale.

The Institute for Research on Public Policy’s Centre of Excellence on the Canadian Federation had already tried to step into the void of data by publishing a “stringency index,” collecting and disseminating information about the public health measures introduced in each province and territory. Government officials and researchers consulted these data regularly. Meanwhile, the IRPP’s online magazine Policy Options was inundated with submissions by experts eager to talk about the impact of, and how to respond to, the pandemic across a range of policy areas. The Institute also published a steady stream of research on the hard-hit long-term care sector.

David had unique insights into how provincial governments dealt with this unprecedented trial. As clerk of the executive council and deputy minister of intergovernmental affairs in Manitoba from May 2020 to November 2021, he had a first-hand view of the range of challenges, experiments and trade-offs that occurred during the pandemic. Now at the Institute on Governance, David wanted to draw out the governance lessons he and so many other public servants had applied so others could learn and benefit.

Therefore, it was through a combination of serendipity, curiosity and a desire to make a difference that we decided to organize a major conference and to publish a report based on what we heard.

If nobody was doing it, we would do it ourselves.

We really knew we were onto something when we started reaching out to potential participants for the conference, set for mid-June 2023 — typically, a very busy time of year. Yes, the invitees said overwhelmingly. An impressive roster of senior public servants, Indigenous and civil society leaders, politicians and other experts was assembled. Canadian scholar and author Alasdair Roberts, professor of public policy at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, signed on to give a keynote speech on “Building an Adaptable Country.”

What we heard was in equal parts frustrating and inspiring. The common feeling was that the pandemic experience was a singular opportunity for the country to make big changes and to build on lessons learned.

While many exhausted Canadians are ready to forget what happened, our leaders cannot — even if they try. Every day, they must deal with a suite of problems exacerbated by COVID-19 — including despairingly long health-care wait times, inflation and lingering public distrust of governments.

Yes, this report is a DIY project — and it is also a big nudge. With their resources, convening power, access to data and behind-the-scenes accounts, governments should take this conversation much further.

Jennifer Ditchburn David McLaughlin

President and CEO President and CEO

Institute for Research on Public Policy Institute on Governance

Executive Summary

The COVID-19 pandemic was a dramatic and unique moment in Canadian history. The impact might have been experienced differently from person to person and community to community, but the crisis experience was a collective one with which we are still coming to terms. Our key institutions were profoundly affected. They were forced to quickly change processes, forge new relationships or strengthen existing ones, and make pivotal decisions at an impossible pace with imperfect data.

There are critical lessons to be learned from that unprecedented time, knowledge that our institutions can apply to future crises.

That’s why the Institute on Governance (IOG) and the Institute for Research on Public Policy (IRPP) partnered to convene the two-day national Resilient Institutions conference in June 2023 in Ottawa. We brought together key decision-makers, practitioners and civil society actors who had been closely involved in the pandemic response to share experiences and ideas on how to make Canada’s institutions more resilient for the future.

We also scanned the national landscape for what other reviews had been done by different orders of government. This report is a summary and analysis of that research and the conversations from the national conference.

Four years after the shutdowns turned our lives upside down, this remains the only pan-Canadian study of its kind. But it is not enough.

How Did Institutions Fare?

We chose to assess four critical institutions: public health, the public service, federalism and democracy.

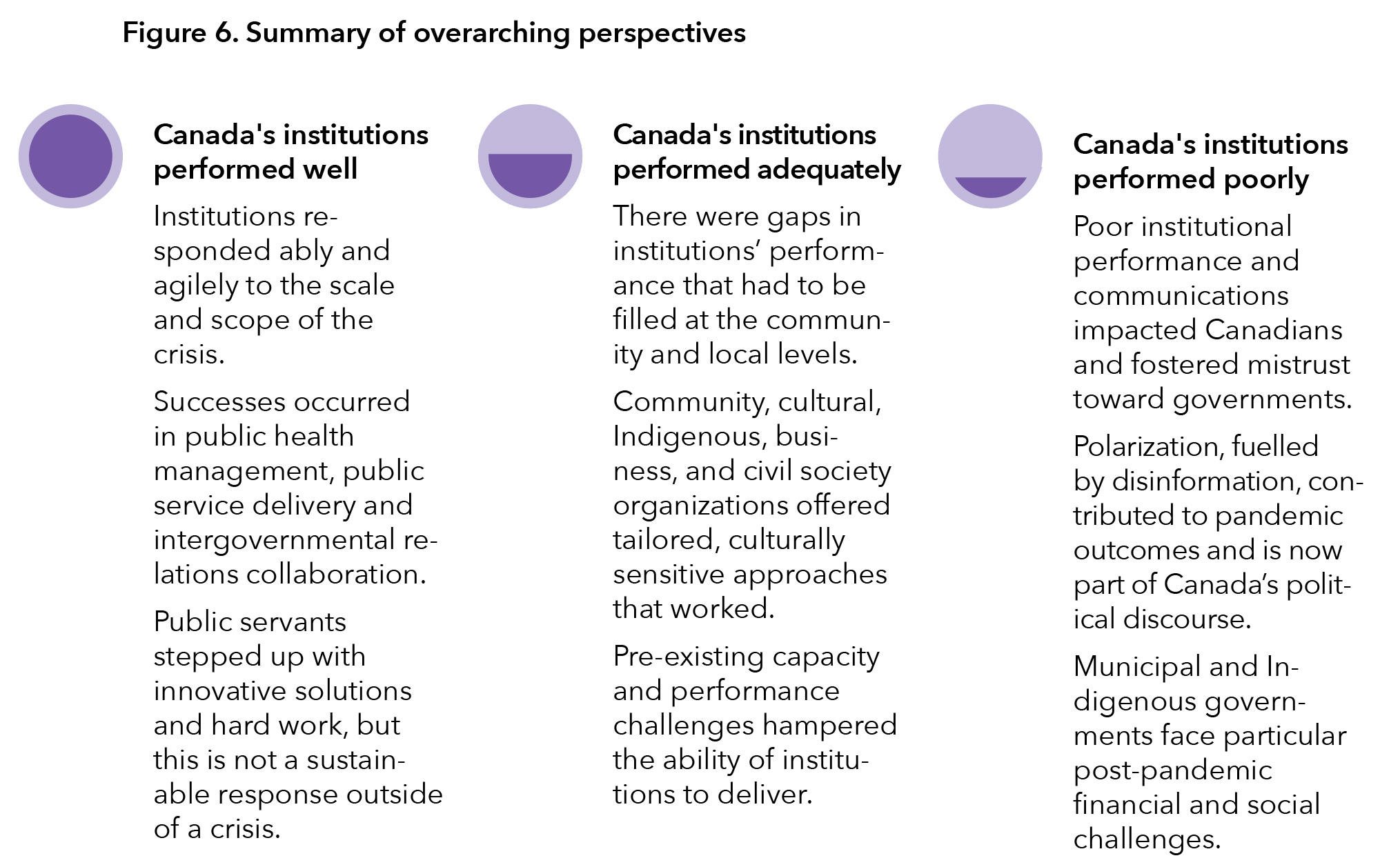

Our roundtable discussions revealed a mixed answer to the question of how Canada’s institutions performed but identified three broad perspectives:

- Canada’s institutions performed well, responding ably and agilely to an unprecedented situation.

- Canada’s institutions performed adequately with gaps and weaknesses that needed to be filled at the community level.

- Canada’s institutions performed poorly with inadequate and wrong responses that affected Canadians and reduced public trust.

The conference consensus was clear: Our institutions did not succeed completely, nor did they fail completely. The pandemic demonstrated how our institutions can be agile and nimble, but it also exposed some serious institutional and governance weaknesses that affected government responses and public health outcomes. Those weaknesses need to be addressed. While it is perhaps unsurprising that we heard a mixed review, it is important for decision-makers to consider the nuanced view that emerged on Canada’s institutional success. These three overarching perspectives are not mutually exclusive. Some institutions were described in successful terms at one moment during the pandemic and in less successful terms at another.

We heard about how Canada’s system of government was able to adapt to keep operating through unprecedented remote-work directives while pivoting to confront the pandemic. Public health measures were implemented quickly and relatively effectively in the first instance, which helped the country manage the onset of COVID-19. Canada’s vaccination program in 2021-22 was particularly successful. Public health co-operation and co-ordination across governments was particularly strong.

Indeed, intergovernmental relations were in many ways more successful during the crisis than in ordinary times. At the same time, we heard that these institutional successes were neither sustainable, due to the tremendous stress they put on the public-sector workforce, nor replicable in the absence of crisis conditions.

Successful outcomes were sometimes accomplished outside — or despite — these same public institutions.

Public institutions entered the pandemic with pre-existing capacity gaps and long-standing challenges, including outdated government data and IT systems and processes. Health-care systems were already operating under strained circumstances with significant human resources constraints, along with data-sharing platforms that were not optimally set up for a crisis.

We heard from community, local, cultural, Indigenous and other groups about the challenges they faced to be meaningfully included in decision-making. Then, we heard about the successes they had in reaching Canadians through tailored and culturally sensitive approaches — strongly suggesting that this should be normalized.

We heard that the pandemic impacted trust in our institutions generally and trust in public health institutions and public health officials more particularly. Perceived policy incoherence and the blunt nature of certain public health measures contributed to widespread pandemic fatigue. That was exacerbated by shifting scientific evidence and advice about how to respond to the virus itself and by inconsistent communication from public officials.

The pandemic shed light on, and worsened, certain relationships in the federation. The early positive tone of first ministers ultimately gave way to more typical arguments and recriminations. We heard about strains on the provincial-municipal relationship, as well as huge financial deficits faced by municipalities that are now on the front lines of addressing other crises, such as housing and opioids. There was also recognition that the health-care system does not serve everyone equitably and that this contributes to the health gaps that were experienced during the pandemic.

Lessons Learned and Recommendations

The report draws out four key lessons that capture the most significant learnings and makes 12 specific recommendations, which are addressed principally to governments and, by extension, all Canadians. They also touch upon civil society organizations and public policy stakeholders. Each recommendation forms part of what the country needs to do to ensure that we learn real lessons from the pandemic and act to make our institutions more resilient in the wake of it.

LESSON 1: INSTITUTIONAL CAPACITY CANNOT BE TAKEN FOR GRANTED

Much of the success of Canada’s pandemic response required individual acts of heroism such as public servants working overtime and creating new relationships on the fly, but this is not sustainable for the long term. To increase our institutional capacity, we make the following recommendations:

- Retool and reinvest in the public service’s digital and IT infrastructure.

- Create more integrated and efficient data-sharing pathways.

- Systematically examine the innovative processes and structures activated during the pandemic.

LESSON 2: THE INSTITUTIONS OF FEDERALISM WORK, UNTIL THEY DON’T

The intergovernmental infrastructure is largely driven by executive federalism, which excludes key actors such as municipal and Indigenous governments. To make the institutions of federalism more resilient, we make the following recommendations:

- Identify the processes and participants that worked best when it came to co-ordinating intergovernmental responses.

- Make intergovernmental relations more inclusive.

- Co-develop and formalize intergovernmental relations with Indigenous governments — a move that will require a shift to viewing them as governments, not just stakeholders.

LESSON 3: LEARNING TO NAVIGATE AND COMMUNICATE RISK AND UNCERTAINTY IS A PUBLIC SERVICE NECESSITY

Although the emergency phase of the pandemic is over, these factors permeate virtually every other potential future policy emergency — including climate change and natural disasters, future epidemics, etc. To better navigate this environment, we make the following recommendations:

- Incorporate positive risk-taking into public service processes to advance innovative ideas, improve service delivery and achieve better outcomes.

- Invest in the new leadership and operational skills development training needed and valued during the pandemic.

- Learn how to communicate policy uncertainty and complexity to Canadians.

LESSON 4: PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS CANNOT WORK WITHOUT PUBLIC TRUST

Public trust was deeply affected by the pandemic and we need to build it back or the next crisis will be infinitely more difficult to overcome. To rebuild this trust, we recommend the following:

- Create a pan-Canadian task force to tackle misinformation and disinformation and help governments understand how to mitigate disinformation/misinformation in future crises that require similar interventions.

- Build inclusive and meaningful relationships with civil society leaders before the crisis hits.

- The federal government should initiate a pan-Canadian comprehensive, collaborative lessons-learned examination that would systematically examine how our public institutions performed during the most demanding public health emergency of our time.

Conclusion

We recognize that we’re only scratching the surface. That is why many of our recommendations call for more to be done. Future studies and reports on Canada’s response to the pandemic should go above and beyond the public health dimension. A narrow health focus would be inadequate in capturing lessons learned. The same can be said for a narrow focus on government spending during the pandemic.

Canada’s COVID-19 response hinged on governance. That means there are key learnings to be drawn about how governments took decisions and who they involved; about how our federation works when governments must work together; and about how information flows within and across governments, and from governments to Canadians.

We hope this report acts as a call to action for governments and civil society to do more now before the natural inclination to “put this behind us” takes hold. It is crucial that our most important public institutions build resilience so they are ready for the next challenges.

Introduction

Those surreal weeks in March 2020 will forever be seared in our memory. Canadians were glued to TVs, radios and their phones, absorbing the news of how the “coronavirus” (as it was called then) was cutting a path of devastation through health systems around the world — and was now in Canada. Government leaders emerged to announce wide-scale shutdowns as part of their official COVID-19 response. Everything suddenly and drastically changed. It was a fearful, uncertain time for all Canadians.

Yet, Canada was not entirely unprepared. Following the 2003 SARS outbreak, Learning from SARS, a review conducted by the National Advisory Committee on SARS, led to new public health mechanisms and measures (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2003). These included the establishment of the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) and the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Public Health Network Council as an intergovernmental forum for collaboration, co-ordination and governance. In 2016, federal-provincial-territorial (FPT) health ministers signed an information-sharing agreement on infectious diseases. The Canadian Public Health Laboratory Network, a network of federal and provincial public health laboratories, became a well-established mechanism to effectively collaborate on laboratory capacity-building and the response to emerging threats.

“Canada has made important gains in terms of our capacity to respond effectively to the public health challenges of serious infectious disease outbreaks. … Key lessons have been learned and milestones achieved that have shaped and sharpened our response approach and structures,” Chief Public Health Officer Theresa Tam wrote at the time of the 15th anniversary of the SARS outbreak (Tam, 2018).

Despite all this, Canadian decision-makers and health systems were overwhelmed by the rapid onset of COVID-19. Information on the virus and how to combat it was disjointed and unevenly applied. Its magnitude and virulence were underestimated and sometimes even ignored. Nothing, it seemed, had truly prepared Canadians for the long, difficult pandemic journey ahead. The toll was enormous, even if better than many countries. Approximately 4.6 million Canadians contracted COVID-19, and more than 51,000 Canadians died by March 2023. Canada’s mortality rate was 135 per 100,000 people by the same date. But some 72 other countries did worse (Johns Hopkins University, n.d.).

Yet, there has been no official, truly pan-Canadian “lessons-learned” commission or study post-COVID. That’s why the Institute on Governance (IOG) and the Institute for Research on Public Policy (IRPP) partnered to convene a two-day national conference in June 2023 in Ottawa. Our goal was to bring together key decision-makers, practitioners and civil society actors who had been closely involved in the pandemic response to share experiences and ideas on how to make Canada’s institutions more resilient for the future. As a result of these discussions, the IOG and IRPP have produced this report on what worked during the pandemic — and what didn’t — to assist governments in planning and delivering public services to Canadians in future crises.

We chose four critical institutions to assess:

- Public health

- Federalism

- Public service

- Democracy

The report focuses on selected key aspects of the pandemic response of each of these institutions. For public health, it was the nature of decision-making, and the availability and use of health data and information. For federalism, it was the early successes and later failures of intergovernmental collaboration, as well as the potential impact on federalism in the future. For the public service, it was internal decision-making, policy innovation, and the capacity and skills of public servants themselves. For democracy, it was the role of politicians and citizens and the impact of the pandemic on public trust.

While we had the generous co-operation of several current and former officials involved in the pandemic response across jurisdictions, we acknowledge that this report only scratches the surface of understanding Canada’s massive and complex institutional response to COVID-19. The conference and subsequent research should not be regarded as a proper substitute for a true national lessons-learned examination led by governments.

The pandemic challenged established conceptions of the role of government, the capacity of the public service, and the needs of the people they serve. Never has Canadian society been so riven by competing expectations of the role of the state and science while confronting issues of trust and disinformation. The collective unwillingness or inability to document what happened and why — including successes alongside the missteps — would be the biggest pandemic failure of all for Canada.

Where This Fits

The conference was not the first exercise to consider the response of Canadian governments to the COVID-19 pandemic. Several governments have conducted assessments and some are still doing so. Nevertheless, the extent of these exercises varies significantly, with many being relatively narrow in scope. Notably, they tend to fall short in comprehensively capturing the interdepartmental aspect, and even more so, the intergovernmental dynamics that unfolded during the pandemic, because these evaluations were predominantly conducted by individual departments on a specific element of the response and because most were done by auditors general. In addition, because these assessments were more often than not internal processes, the involvement of outside experts and larger communities affected by the pandemic was fairly limited, if not completely absent.

This is what the Resilient Institutions conference sought to remedy and where it is unique. It was the first exercise to bring together public servants and elected officials from different orders of government, as well as academics, health-care practitioners and community organizations.

Part I of this document provides a brief overview of reports produced by governments reviewing the pandemic response and describes the context in which the four institutions that were the focus of the event — health, federalism, public service and democracy — had to operate.

Government Reports About the COVID-19 Pandemic Response

It did not take long for some governments to initiate a review of their response — even while the COVID-19 pandemic was in full force. The first was published by Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada in September 2020 (PHAC, 2020) before the second wave hit. Over the following months, the federal government, as well as provincial and territorial governments, conducted a series of reviews of different aspects of their responses. Importantly, the federal government has recently revealed that it has engaged the former chief scientific adviser of the United Kingdom to chair an expert panel to “…conduct a review of the federal approach to pandemic science advice and research coordination.” The aim is to “support Canada’s preparedness for future pandemics and health emergencies” (Government of Canada, 2023e).

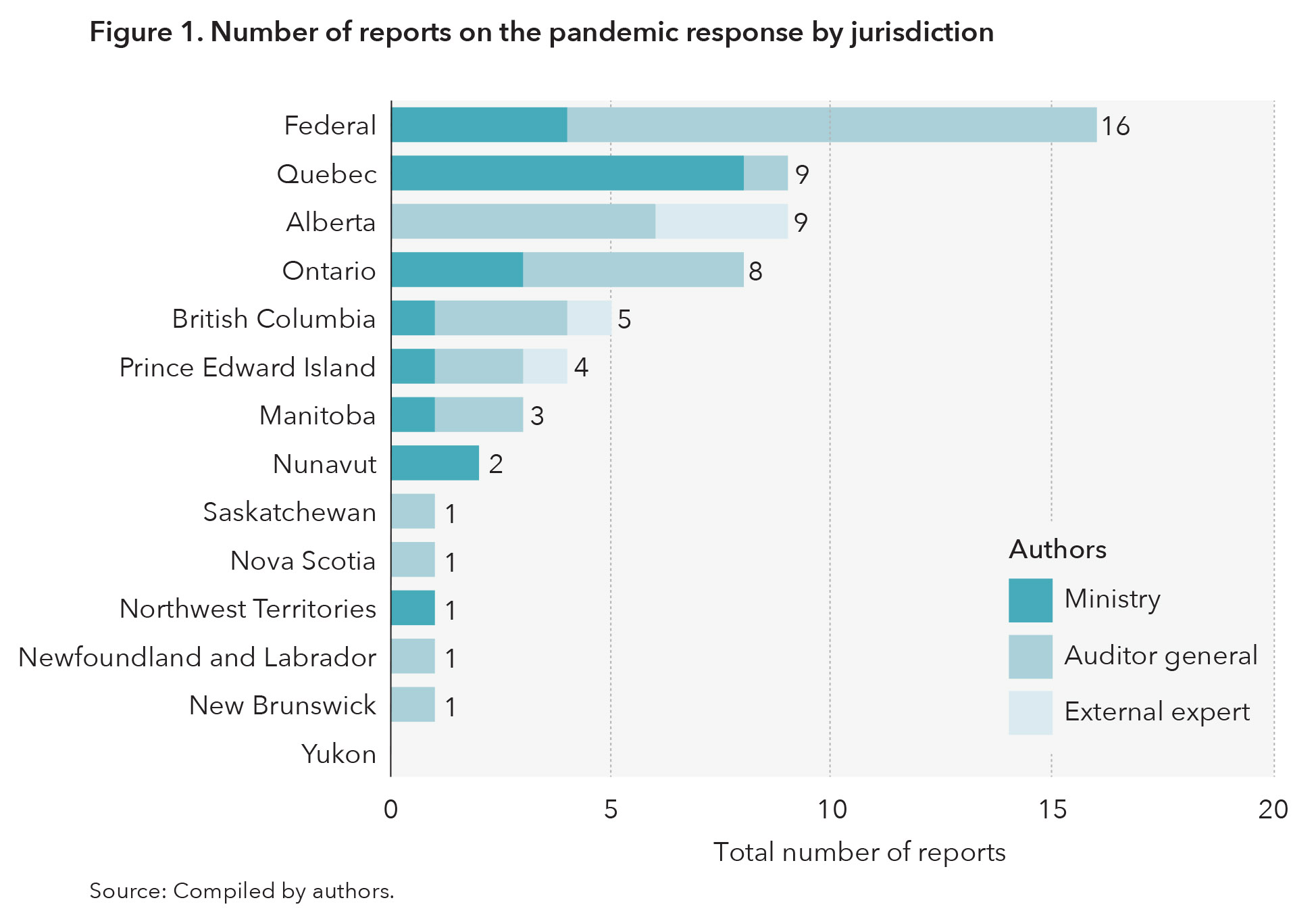

Figure 1 presents reports published by governments reviewing various aspects of their pandemic response (full list of reports in Appendix A). The reports are listed in three broad categories, based on who authored them: auditors general, departments or ministries, and/or external experts.

As the above figure shows, there is a wide variation in the number of public reports that federal and provincial governments produced. Importantly, 38 of the 61 reports captured in this review were written by auditors general. As expected, given their usual mandate, auditors general were tasked with determining if funds were appropriately distributed, with assessing the effectiveness of their distribution and with making recommendations for process changes pertaining to financial support in future emergencies. This was a more narrow, if crucial, review of lessons learned.

However, federal and provincial auditors general did not restrict their analyses to program spending. They also turned their attention to performance audits of pandemic programs. Performance audits of specific FPT programs differ from ministerial reports by also evaluating the effectiveness of a program or its economic or environmental impacts (Office of the Auditor General of Canada, n.d.) but not whether the programs were justified in the first place. These performance audits also determine whether the government had the means to monitor program results, then make recommendations based on their findings on these metrics.

For example, how provinces distributed vaccines was the subject of review by several auditors general. A British Columbia review looked at whether the provincial government was able to get the information it needed to monitor the overall provincial vaccination rate and the vaccination rates in long-term care homes and among health-care workers. The federal auditor general’s vaccination review evaluated whether procurement efforts by Health Canada and the PHAC were sufficient, whether access to vaccines across the country was efficient and if the two bodies were able to sufficiently monitor the distribution of vaccines.

The second type of reports was assessments produced by ministries or agencies on specific aspects of the pandemic. For instance, Quebec’s Commissaire à la santé et au bien-être produced six reports on what happened in long-term care facilities in the province. Quebec had the highest deaths per 100,000 in long-term care in the country in all first three waves of the pandemic (Canadian Institute for Health Information, n.d.-a), which perhaps makes this focus unsurprising. Many other provinces had significant outbreaks in their long-term care systems but did not scrutinize their response to the same extent. A report from the Quebec ombudsperson identified four key failings in the province’s response to outbreaks in long-term care homes:

- lack of sufficient infection-control strategies

- shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE)

- shortages of health-care personnel and related issues

- lack of support for mental health, social isolation and the importance of continuing access for residents to informal caregivers

Reports from the Commissaire à la santé et au bien-être in Quebec and the auditor general of Ontario also included a higher-level view and focused on the failure of governance in long-term care, such as systemic factors that culminated in poor conditions in the facilities and the lack of a reliable, quick data-collection system that made it difficult for decision-makers to have the important information needed to make policy decisions. The reports relied on interviews or surveys of health-care professionals to highlight some of the issues identified in addition to a review of documentation.

Seven ministerial reports included a record of all public health measures taken during the pandemic. Nunavut’s ministerial reports didn’t further analyze these health measures, while reports from the Northwest Territories, Ontario and the federal government used this as a starting point for improving their governments’ emergency preparedness plans. These reports were still ostensibly missing takeaways on the role of intergovernmental co-ordination going forward. The Northwest Territories collected feedback from decision-makers directly involved in the response, the public and Indigenous governments. Alberta, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Saskatchewan and Yukon did not produce ministerial reports or if they did, these were not made public.

Finally, the third type of review — those done by an external group of experts — is the one that was the most limited. We identified four of them, each with a very different format: three in Alberta and one in British Columbia.

In Alberta, the government commissioned KPMG, a professional services firm, to review the province’s overall response to the first wave of the pandemic, covering actions taken between March 1 and Oct. 20, 2020. The report was released in January of 2021. KPMG’s review was broad-based and looked at the acute-care response, continuing care response, engagement and communication strategies, procurement and PPE strategies, as well as governance and decision-making.

In 2023, Alberta also commissioned a report from a panel chaired by Preston Manning, former leader of the Reform Party. That report differed from the KPMG report by looking at “legislation and governance practices” (Manning et al., 2023, p. 5) during the pandemic. It included a public opinion component — an element missing from the KPMG report — by inviting the public to answer the question: “What, if any, amendments should be made to the legislation that governed Alberta’s response to COVID-19 in order to better equip the province to cope with future public health emergencies?” (Manning et al., 2023, p. 8).

Alberta also appointed an expert advisory panel to review children’s and youth’s well-being during the pandemic. That report was released in December 2021.

British Columbia commissioned a lessons-learned report from three former public servants who were tasked with undertaking “an operational review of the B.C. government’s pandemic response to help the government prepare for future events” (de Faye et al., 2022, p. iii). However, the approach and topics of interest between the B.C. report and the KPMG and Manning reports in Alberta differed substantively in composition and mandate, and the extent to which the public, First Nations and various stakeholders were consulted. The B.C. report also included recommendations on public trust of government, preparedness, implementation strategies and an entire section on Indigenous impacts. KPMG’s report for Alberta and the B.C. lessons learned reports looked at decision-making and communication strategies.

To summarize: Some aspects of the pandemic response have been reviewed by governments trying to identify lessons learned and to improve processes. But these have been intermittent and highly targeted. Certainly, no comparative or pan-Canadian review has been attempted. Although we can learn something from all these different lessons-learned reports, they leave large areas of the pandemic response unexamined, especially as it pertains to governments interacting with each other. In addition, the number of these exercises that were large in scope and encompassed various aspects of the different governments’ actions during the pandemic was limited, with nothing resembling the work of a comprehensive national review — something that others have urged (Bubela et al., 2023).

However, it is important to highlight that this short overview of governments’ assessments relies on publicly accessible content and therefore may potentially underestimate the depth and breadth of retrospective analyses, especially as COVID’s legacy unfurls. Notably, there has been nothing at the national level of common interest to all Canadians. We revisit this question in the lessons and recommendations section of this report.

The lack of comprehensive, public post-pandemic assessments by governments reinforced the importance of the Resilient Institutions conference. There was a particular need to bring together decision-makers, practitioners and observers from different jurisdictions who could share experiences that would reveal common or unique perspectives of deeper value than any single individual organizational or jurisdictional review. There was also a need to do so while events and actions were relatively fresh in people’s minds.

The Four Institutions

The conference created a unique opportunity to cultivate dialogue among various actors on four overarching institutions that were affected by, and relied upon during, the pandemic: public health, federalism, the public service and democracy. In addition to being central to the Canadian COVID response, these institutions are also the most important to be reinforced post-COVID. Below, we briefly summarize the context through which participants at the conference — each from one of these institutions — had to navigate during the pandemic, setting the stage for the conference’s discussions.

Public Health

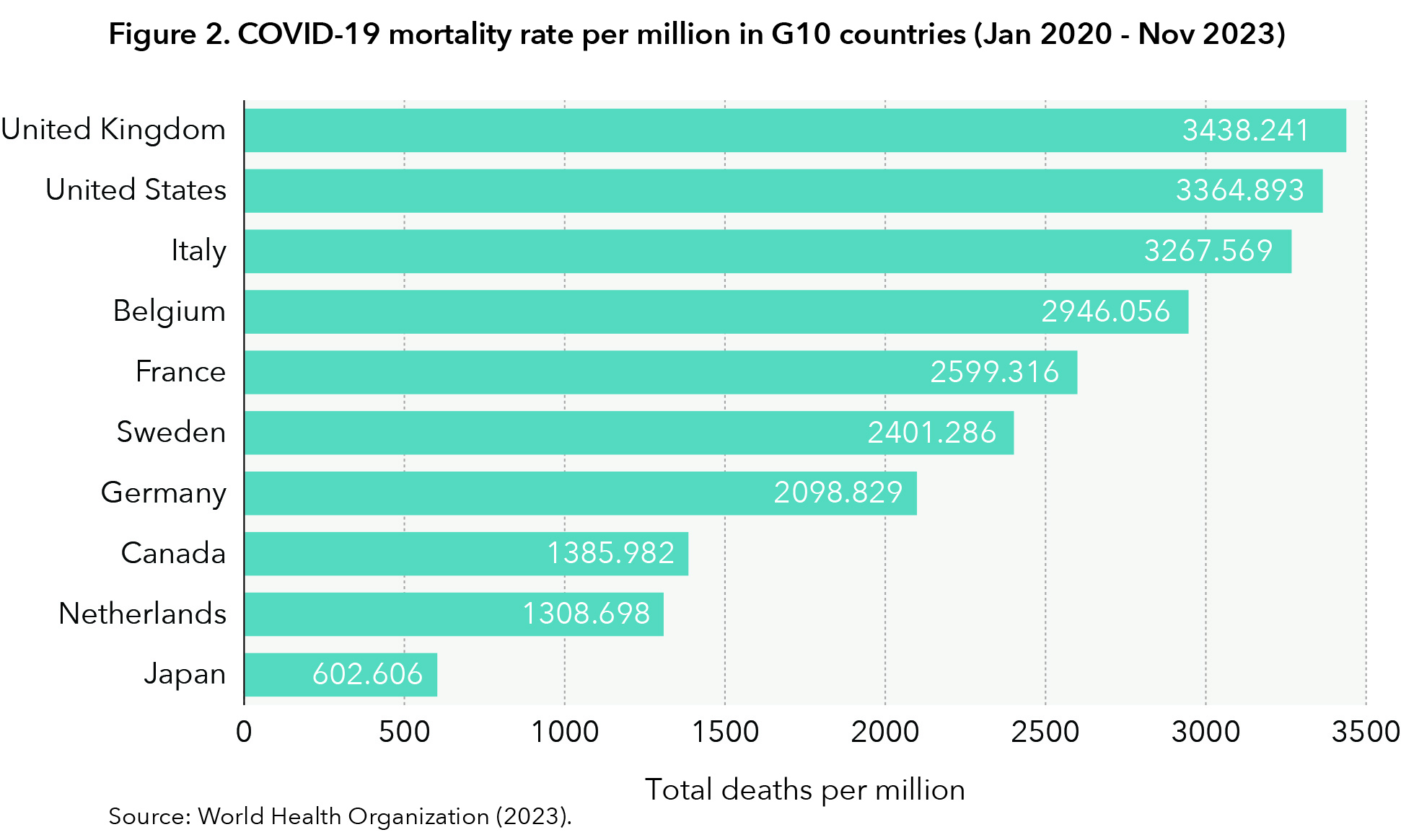

Helen Angus, former Ontario deputy minister of health, wrote in a commentary in Policy Options that “while not every decision was a good one,” Canada’s institutions worked largely as they were designed (Angus, 2023). Canada fared better than most G10 countries (apart from Japan and the Netherlands) for COVID-related mortality (Razak et al., 2022), as seen in figure 2.

However, as the pandemic spread across Canada, decision-makers faced long-standing structural challenges in health care and public health — chief among them a landscape that included a multitude of actors across jurisdictions who faced significant human and financial resource constraints, as well as barriers to data sharing.

Key actors in Canada’s pandemic response

At the federal level, decisions around the pandemic were primarily made through a cabinet subcommittee, which provided whole-of-government co-ordination and leadership. This committee was created on March 4, 2020, and worked in conjunction with the existing incident response group. The incident response group is an ad hoc working group of relevant ministers and senior government officials and was convened to discuss COVID-19 for the first time on Jan. 27, 2020 (Office of the Prime Minister, 2020). Additionally, the PHAC disseminated health information and guidance on the pandemic response at the federal level. It also disseminated pandemic advice and provided information to ministers through the federal-provincial-territorial (FPT) special advisory committee on COVID-19.

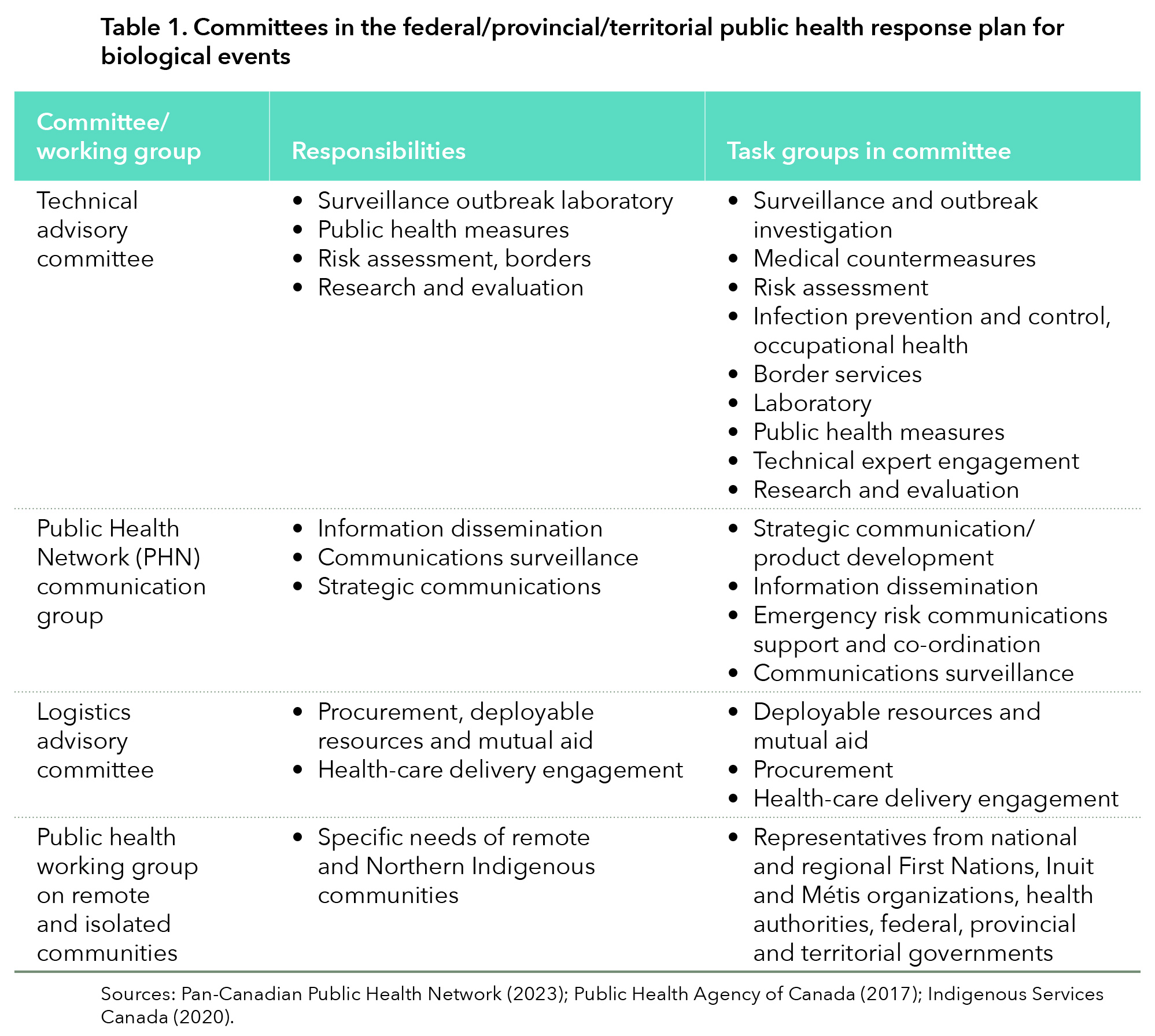

In January 2020, Canada put into place the federal/provincial/territorial public health response plan for biological events, which activated several committees and associated secretariats to facilitate the public health response (Pan-Canadian Public Health Network, 2023), summarized in table 1 below:

The committees in table 1 provided support to the special advisory committee that developed the federal, provincial and territorial public health response plan for ongoing management of COVID-19 (Government of Canada, 2022). This plan was not intended to serve as a list of obligations but instead laid out pan-Canadian considerations as governments transitioned out of the pandemic. For example, it included public health objectives, forward-planning assumptions and an overview of potential consequences of the pandemic response (Government of Canada, 2022).

At the provincial level, chief medical officers of health (CMOH) were key actors in the pandemic response. For many Canadians, CMOHs were some of the most visible public officials throughout the pandemic, appearing either independently or alongside premiers and ministers.

Crucially, the role of CMOHs is highly dependent on the institutional and legislative landscape and varies from one province to another. CMOHs can be placed along a continuum on two dimensions: their advisory capacity and their communication role (Cassola et al., 2022). In Canada, Cassola et al. (2022) identify three general models: technical expert, everybody’s expert, and loyal executive. These three models illustrate the range of reporting responsibility to the public and advisory responsibility to governments that CMOHs have.

As the pandemic showed, the CMOH role can evolve in response to or because of changes to legislation or relationship with the government, amongst others. For example, all CMOHs increased their communications to the public during the pandemic. Broadly, these communications fell under four themes: describing preparedness and capacity-building; issuing recommendations and mandates; expressing reassurance; and promoting public responsibility (Fafard et al., 2020). In addition to communications within their jurisdiction, CMOHs also periodically released joint statements through the Council of Chief Medical Officers of Health and exchanged information about the pandemic situation in their respective jurisdictions.

Resource constraints

Inadequate human resource capacity in health care is a core structural issue in Canada’s public health system. In general, Canada has fared average or below average across five metrics compared to its Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) peer countries. There are 2.8 doctors/1,000 population, lower than the OECD average of 3.7 doctors/1,000, and 2.6 hospital beds/1,000 population, lower than the OECD average of 4.3 beds/1,000 population. Canada’s performance on nurses per capita (10.3/1,000), is slightly higher than the OECD average (9.2/1,000) (OECD, 2023). The OECD does find that these capacity metrics are improving, except the number of hospital beds, which actually decreased over time.

Human capital is not the only resource constraint on public health capacity. The latest available data from the OECD show that, despite Canada spending US$6,319 per capita on health, higher than the OECD average of US$4,986 per capita (OECD, 2023), there are still long surgery wait times (Canadian Institute for Health Information, n.d.-b.), lack of access to a family doctor (CIHI, 2023) and emergency rooms at maximum capacity (Varner, 2023). For provinces and territories, health-care spending is the top expenditure (Statistics Canada, 2022a). Projections of demographic changes in Canada suggest health-care costs will rise as the population ages and requires more support across hospitals, long-term care homes, hospice care and in their communities.

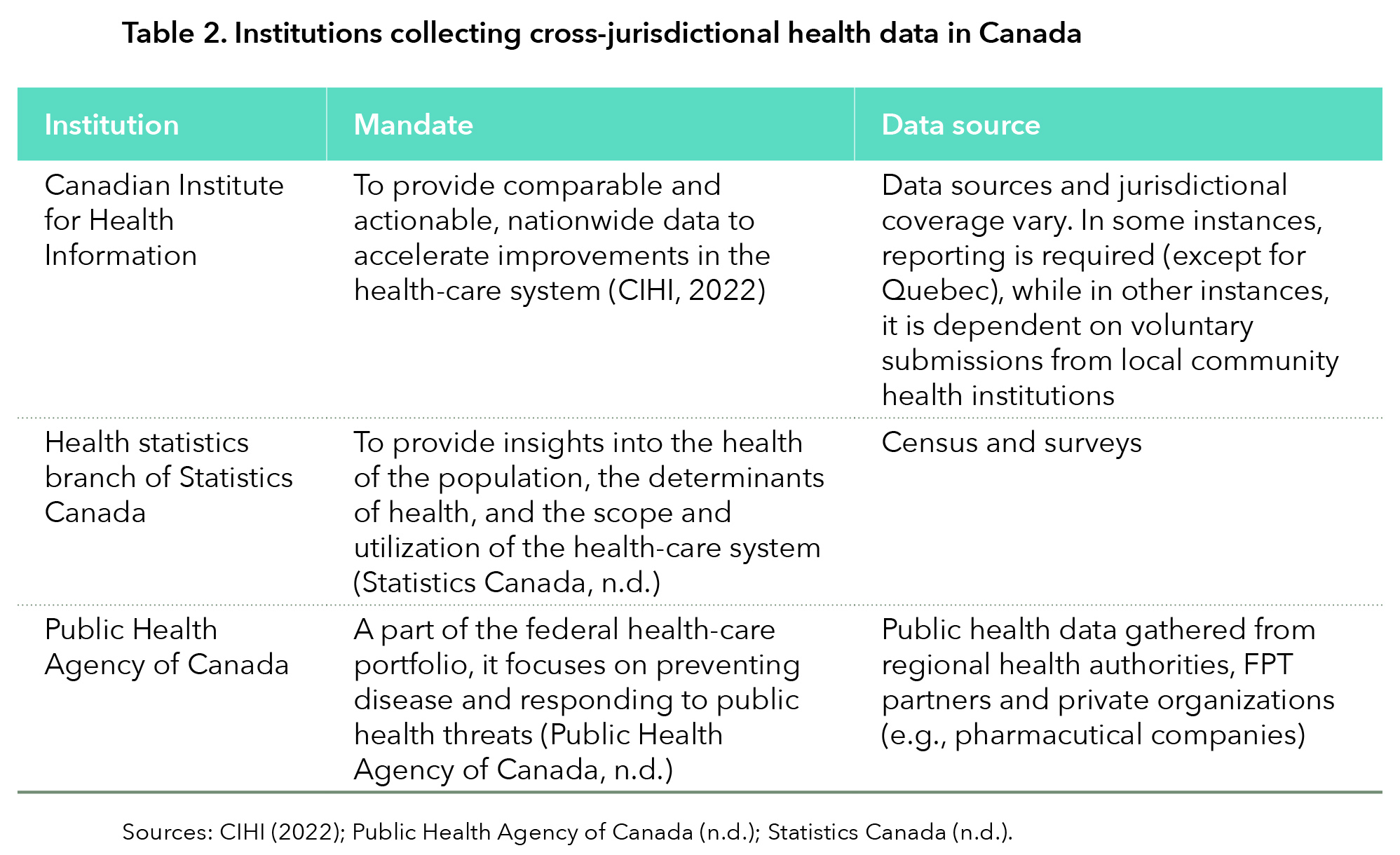

Data

Cross-jurisdictional data, such as administrative health data, are difficult to access in Canada because data governance practices differ from province to province. Many of the health data available are sourced from information collected by regional health authorities, surveys, and provincial and territorial departments. Statistics Canada and the PHAC are responsible for collecting and utilizing these data to create pan-Canadian databases for the benefit of policymakers and researchers on the governmental side, while CIHI is the only independent organization to do this work.

If pan-Canadian data are not aggregated by these organisations, decision-makers looking to make comparisons between provinces and territories must turn to provincial/territorial or regional sources. Each jurisdiction’s data are governed by a different institution. For instance, Katz et al. (2018) is a case study of the hoops through which researchers have to jump to access administrative health data. Their attempt to disentangle varying data governance systems across the country reveals a high administrative burden to access data across multiple jurisdictions. A key issue is how the institutional homes of administrative health data are different from province to province. For example, in Manitoba, provincial health data are housed at the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy at the University of Manitoba, which acts as a steward of information (University of Manitoba, n.d.). Conversely, in Alberta, administrative health data are collected and managed by a branch of Alberta Health Services. This barrier makes any jurisdictional comparison a resource-intensive endeavour.

Indigenous health care and data

Indigenous health care is funded, governed and delivered by both federal and provincial governments and in some scenarios by health authorities within Indigenous communities themselves. Within the federal government, Indigenous Services Canada provides direct funding of certain health services to First Nations and Inuit communities (Indigenous Services Canada, n.d.). Health Canada and the PHAC contribute to programs that support Indigenous Peoples living in urban settings or in Northern communities (Indigenous Services Canada, n.d.) Provinces indirectly support Indigenous health care because of their constitutional responsibility to implement health-care services for all inhabitants of the province.

In recent years, there has been a slow shift toward recognizing the inherent right of self-government for First Nations, Inuit and Métis, including when it comes to health care. This right has manifested in different ways across Indigenous communities. Most notably, in 2011, a tripartite framework agreement was signed by First Nations, the federal government and the B.C. government, leading to the creation of the First Nations Health Authority (FNHA) in 2013 (Indigenous Services Canada, n.d.), the first and only FNHA of its kind. The FNHA took over responsibility for programs previously administered by Health Canada (including direct provision of primary health care) and champions “culturally safe practices” throughout the broader health system (FNHA, n.d.). While this model has not been replicated in other provinces, there have been tripartite agreements signed to improve Indigenous governance of health care in Manitoba, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Ontario and Quebec (Indigenous Services Canada, n.d.).

More attention was paid during COVID-19 to the impact on Indigenous communities than there had been during previous health emergencies. However, data availability was still poor and there is still no complete picture of how Indigenous communities fared, compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts. Instead, individual studies and information directly from Indigenous health leaders present a fragmented picture of the reality on the ground. One study found that, while infection rates were higher in non-First Nations individuals at one point during the pandemic, this dynamic flipped after Nov. 30, 2020, when COVID-19 began to spread to these communities (Mallard et al., 2021). Another study showed that mortality rates also followed this pattern (Tripp, 2022). Still, the lack of discrete health data for Indigenous populations before and during COVID-19 was a major hurdle to overcome in providing effective public health responses.

The availability of data on vaccination rates for First Nations people is slightly better than the information we have on Indigenous COVID-19-related infection and mortality. As of Sept. 5, 2023, the federal government reported that 93 per cent of First Nations people living on reserves had received their second dose and 40 per cent had received their third dose (Government of Canada, 2023a). There aren’t clear data for the overall rate of vaccination for Indigenous Peoples living off reserve. One study found that rates of vaccination for First Nations, Inuit and Métis people living in Toronto and London, Ont., were lower than city wide rates. Rates of vaccination (second dose) among First Nations, Inuit and Métis in Toronto were 58.2 per cent, and in London, 61.5 per cent (Smylie et al., 2022). For comparison, the overall rate of people who had completed their primary series[1] in Canada was 80.5 per cent (Government of Canada, 2023b).

Federalism

The pandemic made federalism real for many Canadians. For the first time, their ability to meet with their loved ones, leave their homes and even where they could shop depended on the province or territory in which they lived. There were similarities but many differences.

The Centre of Excellence on the Canadian Federation’s COVID-19 Stringency Index (figure 3) tracked these discrepancies by looking at public health measures such as school closures, business closures, vaccination passports and masking policies (Breton et al., 2021). In general, it found that most provinces experienced three peaks in stringency corresponding to their respective COVID-19 waves. However, the suite of measures used to control the pandemic differed from location to location, depending on governmental priorities. One example with significant variation was school closures. Some decision-makers argued that school closures should be a last resort, but the reality was that this was not always reflected in which measures provinces and territories chose to implement. A Policy Optionsarticle comparing school and restaurant closures found that provinces such as Ontario and Quebec had more days when restaurants were closed than schools, while provinces such as Nova Scotia and Manitoba had more days when schools were closed than restaurants, with other provinces falling somewhere between (Han & Breton 2022). The variability meant that Canadians across the country experienced pandemic restrictions in different ways.

But public health measures were just one part of the intergovernmental response to COVID. There were three main responsibilities of the federal government and federal agencies during the pandemic: providing guidance and direction for national co-ordination; control of international borders; and regulatory approval and procurement of the necessary medical supplies and vaccines (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2017). The federal government also created an FPT table for COVID-19 communications to facilitate dialogue between actors who may not normally exchange information, as well as to develop best communications practices, to spread information widely about the changing nature of the pandemic. Additionally, the federal government engaged external actors for feedback on communications efforts.

The federal government had responsibility for approving, procuring and distributing vaccines as well as other supplies to provinces and territories. This was a particularly crucial task because of the fierce global competition. As of July 14, 2023, 121,598,900 vaccine doses were purchased and distributed across Canada (Government of Canada, 2023c). Canada wound up with one of the highest vaccination rates in the world (Our World in Data, 2024).

The federal government also provided financial support of $19 billion to provinces and territories to mitigate stress on their health-care systems, to improve capacity for contact tracing and outbreak management, and to build out social services for Canadians through the safe restart agreement, which aimed to help provinces restore their economies (Government of Canada, 2020). Primary responsibility for the national economy rested with the federal government. It had the spending power to prop up livelihoods quickly and decisively.

The provincial and territorial governments’ responsibilities mainly centred around the provision of health-care services within their jurisdiction. The administration of some health systems was also delegated to regional or local public health units. For most Canadians, the provinces were the governments that had the most direct impact on how they experienced the pandemic. Given that this was a public health emergency, this is not surprising. Provinces were responsible for formulating and implementing public health restrictions; enforcement for schools and businesses; instituting limits on the size of gatherings; scaling vaccine administration; imposing travel restrictions; and masking (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2017). Provinces also took on the role of the main source of information about COVID-19 to their residents through daily updates from premiers, ministers of health and public health officials.

Mechanisms of co-ordination

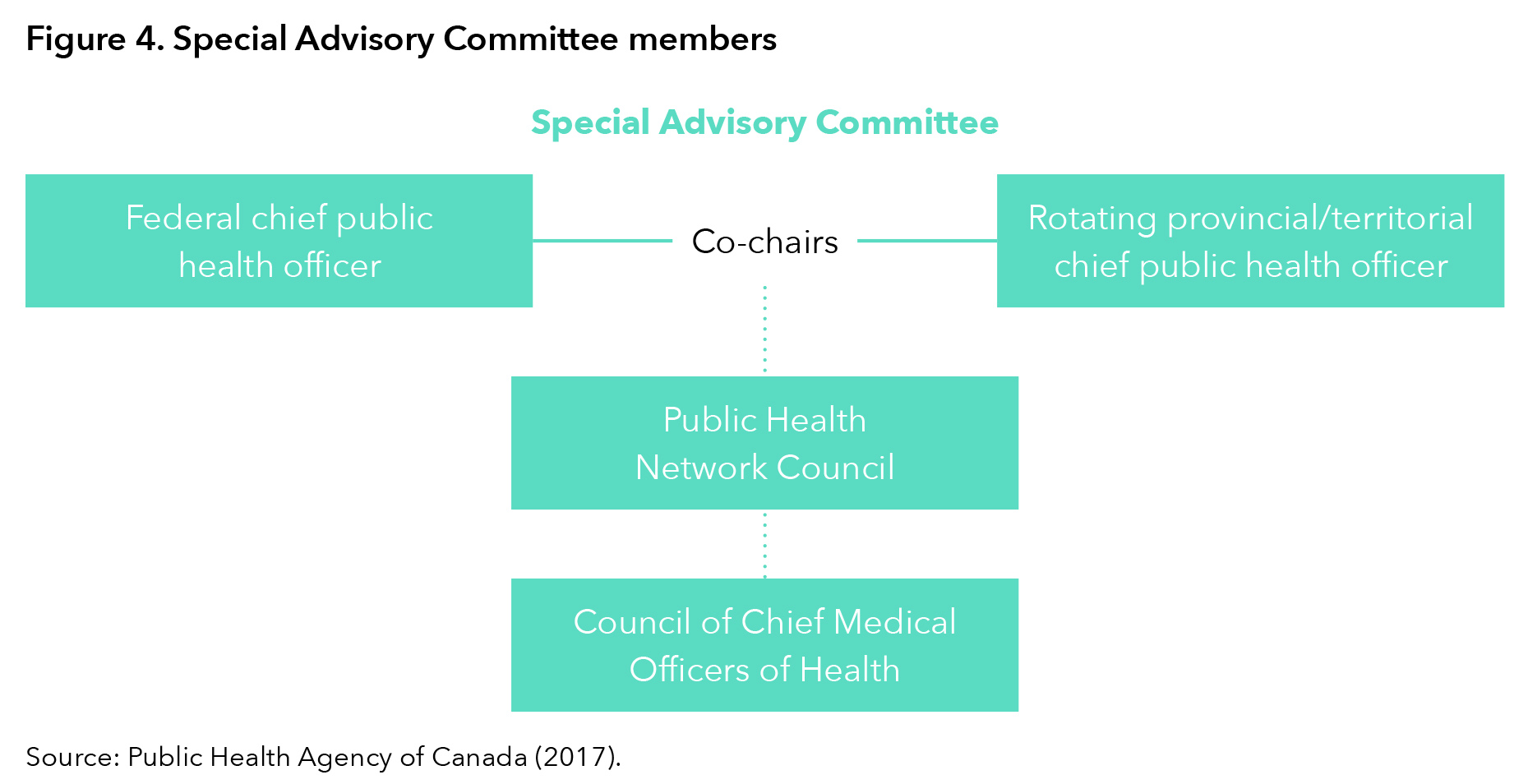

The pandemic required unprecedented levels of intergovernmental co-ordination to grapple with a virus that spread quickly across international and domestic borders. Co-ordination and information exchange between different jurisdictions happened mostly through informal (i.e., not constitutionally grounded), ad hoc forums. The division of federal, provincial, and municipal governments was laid out in the federal/provincial/territorial public health response plan for biological events. The plan includes a pathway for public health experts to give health advice to FPT deputy ministers of health through the special advisory committee (SAC). (See figure 4 for SAC membership.)

The federal-provincial-territorial relationship was co-ordinated mainly through first ministers’ meetings involving Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and the leaders of the 13 provinces and territories. While historically these meetings had been called on an ad hoc basis, they were called weekly during a significant portion of the pandemic. The exact number of meetings between the premiers and the prime minister during the pandemic is not publicly available, but the available numbers reinforce the heightened intensity in intergovernmental co-ordination during this time. As of Dec. 14, 2021, there had been 35 first ministers’ meetings (Office of the Prime Minister, 2021). Another avenue of intergovernmental co-operation on public health was a series of meetings of the FPT ministers of health and deputy ministers of health. As of November 2022, there had been 57 meetings of FPT ministers of health (Government of Canada, 2022).

The COVID-19 vaccination campaign was the largest mass vaccination campaign in Canadian history and exemplifies the elevated level of co-ordination and communication that was necessary between FPT governments. The federal government was responsible for procuring vaccines and for the regulatory approval of these new medicines. It had to make decisions about vaccine allocation between the 13 provinces and territories, as well as for Indigenous Peoples. Then, provincial governments had to make decisions about which jurisdictions should be prioritized and why; create plans for distribution; collect data around the immunization strategy; conduct community outreach; communicate emerging information about the vaccination to the public; and create strategies to combat vaccine hesitancy.

Other governments

Other orders of governments were central to the pandemic response despite being outside the core intergovernmental relationships described above. Municipal governments were often responsible for the first response to COVID-related policy implementation. While guidance and policy direction came from the provincial and federal levels, local health units were the figures on the ground involved in direct contact with the public. Municipal governments’ capacity to carry out policy direction was strained during the pandemic because they experienced extraordinary financial pressures due to the loss of revenue from changes in the population’s behaviour. For example, many public transit systems reduced service because of a migration of workers from the office to working from home — a shift that has been maintained in part long after the pandemic. Similarly, Indigenous leaders also bore responsibility for some aspects of policy implementation, with mixed degrees of support from federal and provincial governments. Panellists from our Resilient Institutionsconference argued that the lack of support was fuelled partly because of confusion from FPT governments about who was responsible for supporting Indigenous communities.

The Public Service

The public service was challenged more than ever by the pandemic. Almost overnight, governments across the country were faced with new priorities and an urgent need to adapt their ways of working. Citizen demands on governments increased and the crisis required the rapid development and rollout of various emergency relief measures and other public services. Only in 2024 is the last of these measures — small business loan support — being wound down. Frequent public communication and briefings from public servants to elected officials and the public became the norm. These impacts continue to be felt in the post-pandemic environment. As the deputy ministers’ task team on values and ethics noted in its 2023 report to the Clerk of the Privy Council: “The pandemic dramatically changed how the public service works, impacted citizens’ trust in public institutions, increased their expectations and diminished their overall satisfaction with government services” (Government of Canada, 2023d, p. 4). This is as good a summation as any.

Public service adaptations

There are numerous examples of the public service at several levels of government reconfiguring to meet the scale and nature of the crisis. What follows is a non-exhaustive sampling of some of those adaptations. In Ontario, the health command table, reporting to the minister of health, was set up to act as a single point of oversight and executive leadership for the province’s response. The province pivoted by adding more personnel to the Ministry of Health and other core ministries, adapting existing supply-chain work to focus on the procurement of PPE and increasing the Ministry of Health’s spending authority (Angus, 2023). Outside the health realm, the Ministry of the Attorney General pivoted by establishing a virtual court system to ensure continued proceedings (Adach, 2020).

The independent review of British Columbia’s operational response describes how the provincial government modified its approach to public service delivery. Employee resources were reallocated to support response programs, while ministries adapted to deliver some services online and rapidly made adjustments to maintain essential in-person service delivery. According to the authors, the task of configuring service delivery and providing necessary new services was “undertaken very rapidly, in days or weeks making changes that normally would take months or years to design and implement” (de Faye et al., 2022, p. 91).

The first volume of the New Brunswick auditor general’s performance audit on the pandemic illustrates how the government reconfigured typical executive council, cabinet and committee processes to get information more quickly to decision-makers and to facilitate rapid decision-making. The audit says: “The time required to bring information to decision makers was expedited from weeks, to at times, just hours” (Auditor General of New Brunswick, 2023, p. 33). This was achieved, among other measures, by assigning briefing responsibilities (which normally involved multiple steps and could take weeks) to the COVID core committee, a group of senior government officials, including the clerk of the executive council, the minister of justice and public safety, and the deputy minister of health (Auditor General of New Brunswick, 2023).

Manitoba experienced a relatively mild first wave of COVID-19, compared both to other jurisdictions and to what was to come. Pandemic responses were led by public health with an ad hoc committee of deputy ministers supporting it. Once the second wave of the virus became likely, a whole-of-government pandemic co-ordination response was deemed necessary. A COVID co-ordination committee (CCC) of all relevant departmental deputy ministers was established and chaired by the clerk of the executive council, including the chief medical officer of health, the chief nursing officer and other Manitoba Health representatives. This became the principal pandemic advisory and decision-making organ of the government. To facilitate ongoing cabinet engagement, several ministers were either invited or participated regularly to stay abreast of developments and to ask questions of officials. Daily CCC meetings were held, led off with a CMOH report on the state of the virus and health system impacts. Stand-alone task forces were established on testing, contact tracing, vaccination and enforcement to quickly ramp up the province’s capacity to respond to pandemic trends and developments. Information dashboards and COVID-19 modelling were regularly provided to the CCC. Health system representatives and Indigenous health services representatives attended, as required, to update participants on developments in their areas and to assist in co-ordinating responses.

What is clear in each of these examples is that existing governance structures and processes were inadequate to address the scale and scope of an effective pandemic response. New ones had to be created and old ones adapted to manage through this new reality.

Public servant adaptations

Public servants themselves faced new demands and demonstrated incredible dedication to tirelessly deliver services for Canadians (Wernick, 2023). These efforts took place in an entirely new working reality. On March 13, 2020, a work-from-home order for most federal public servants came into effect. The federal government rapidly modified its 1999 telework policy, then issued several new policies and directives in the two years that followed, including an easing of restrictions that led to the adoption of hybrid work models (Champagne et al., 2023). Prior to the pandemic, work-from-home had been limited, so the federal government needed to dramatically and rapidly enhance its remote work capabilities, such as increasing bandwidth, creating platforms for communication and enabling remote access, including for sensitive information (Shared Services Canada, 2021). Similar approaches were taken at different levels of government.

The unprecedented working reality undoubtedly took a toll on the public servants themselves. Burnout in the federal public service had previously been noted as a challenge and some studies pointed to a rise in burnout corresponding to the pandemic period (May, 2022). A 2021 study of the psychological health of a sample of Statistics Canada employees by creating a typology of psychological health and work engagement profiles found that 15 per cent of employees were “thriving,” 34 per cent were “doing well,” 38 per cent were “moving along” and 13 per cent were “struggling” (Blaiset al., 2023).

Long-standing challenges

Public services across Canada entered the pandemic facing a host of pre-existing institutional challenges. Public administration expert Amanda Clarke points to long-standing issues in the federal public service, including over-engineered processes, risk aversion, limited collaboration and outdated corporate policies related especially to IT and HR (Clarke, 2023). These factors would prove to be additional barriers that civil services needed to overcome when faced with the COVID crisis. They loom large in influencing how governments could, and did, respond to the pandemic.

Democracy

The pandemic had a profound impact on Canada’s democratic institutions, social discourse and trust in public institutions. The early days of the crisis were characterized by cross-party collaboration, public solidarity and a collective commitment to “flattening the curve.” Politicians worked across party lines to pass relief measures for Canadians while fear of the virus contributed to a period of high trust in elected officials (Turnbull, 2023). None of this lasted, however, as tensions arose around vaccination procurement and dispersal, mask mandates, lockdowns and the resultant disruptions to life and work. The political peace and collegiality that saw Canada through the first stage of the pandemic deteriorated as fatigue with pandemic measures set in and people became increasingly frustrated with what they saw as unnecessary government intrusion. Shifting information on both the virus and what to do about it contributed to this rising frustration.

Tensions culminated in the convoys and blockades in Ottawa and elsewhere during which public health measures were decried for their impact on individual freedoms. Although the number of actual participants in these activities constituted a very small percentage of the population, an Ekos Research poll found that 25 per cent of Canadians supported the convoy’s stated goals. However, it also found a positive correlation between support for the convoy and high levels of disinformation and mistrust (Ekos Politics, 2022).

The COVID-19 pandemic period both created and exacerbated social divisions. For example, higher earners were more likely to hold “pandemic-resilient” jobs that could be done remotely as compared with lower-paying jobs that experienced high volatility during the pandemic (Statistics Canada, 2022b). People’s trust in one another also varied along socio-economic lines. A study by Wu et al. found that peoples’ social trust, or trust in others, increased between 2019 and 2021 for those in higher socio-economic brackets and decreased for those in lower socio-economic positions (Wu et al., 2022).

Public trust

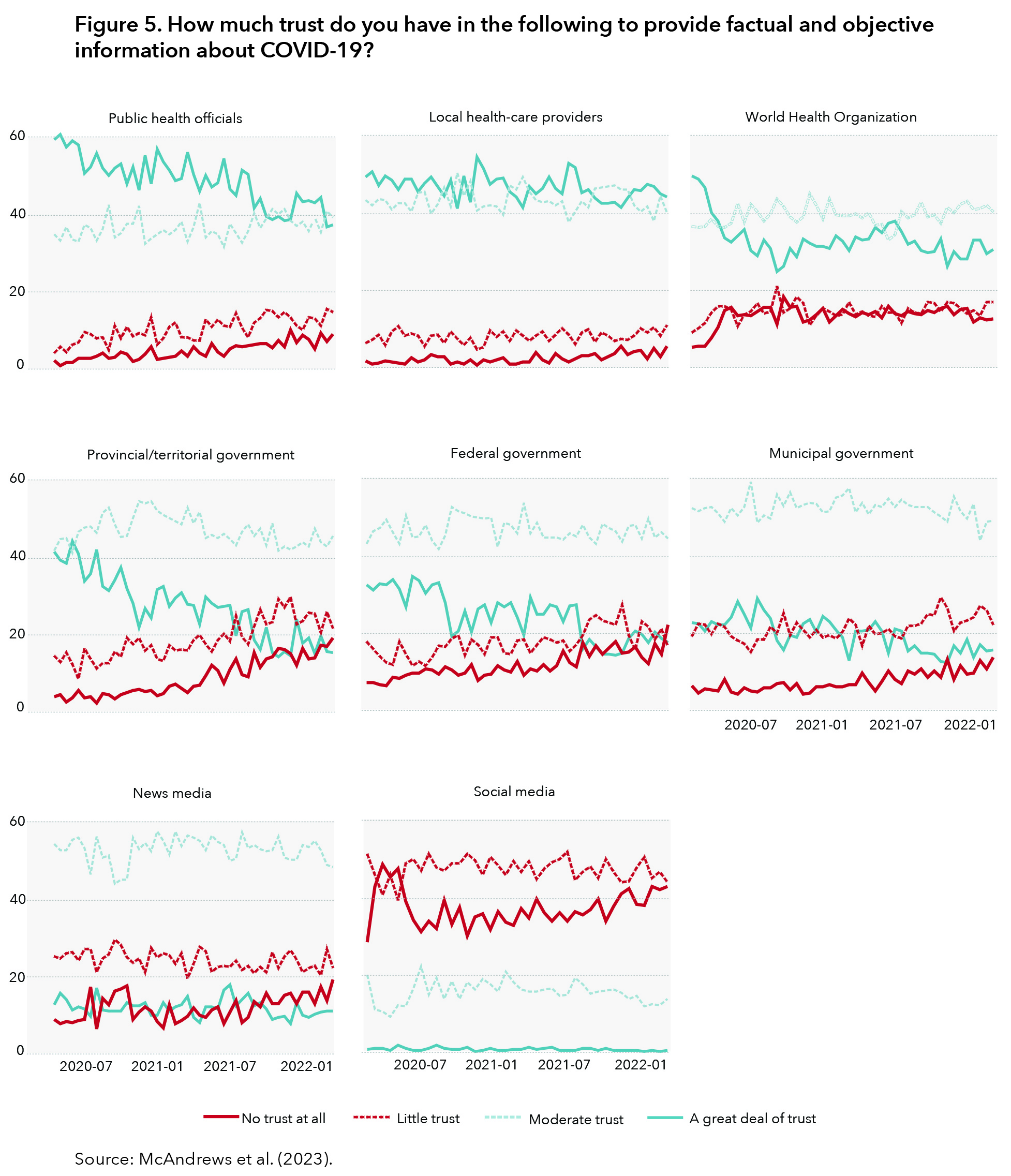

Public trust was a key factor in ensuring adherence to public health measures, but levels of trust were by no means stable throughout the crisis. In their Policy Options article commissioned for the conference, McAndrews et al. trace the evolution of public trust in institutions, specifically examining whom Canadians trusted to provide them with reliable information about the pandemic (McAndrews et al., 2023). Canadians generally put the most trust in health experts, including public health officials, local health-care providers, and the World Health Organization. Social media was the least trusted. There was a decline in trust in all eight institutional actors observed in the study by 2022. See figure 5.

Public institutions gain and lose trust for various reasons. An OECD model sets out five indicators that are thought to influence levels of trust in government: reliability, responsiveness, integrity, openness and fairness. A study by the Institute on Governance examined Canadians’ trust in government using a unique AI model that tracked Twitter data between December 2020 and December 2022. The study found relatively stable average trust in government over the two years but found high variability to specific events. A key finding was that government responsiveness (meaning the extent to which they effectively delivered services and programs) and openness were the most salient of the five components (Institute on Governance, 2023).

Public trust does not exist in isolation. It is formed and informed by multitudes of information sources grafted onto pre-existing biases, perceptions and experiences, both personal and collective. Vaccine hesitancy, for example, was rooted in deeply personal views about science and bodily choice. Opposition to masking and public health restrictions stemmed from world views about personal liberty, community values, religious convictions and government coercion. While the vast majority of Canadians got vaccinated to protect themselves and to help end the pandemic, a sizable minority refused. Paradoxically, it was only when the Omicron variant took hold — infecting even some of those who had been vaccinated — that the divide appeared to lessen. Overall then, the pandemic has had a profound effect on our democratic and public institutions, highlighting enduring challenges concerning trust that persist to the present day.

[1] Primary series means one dose for a one-dose vaccine or two doses completed for a two-dose vaccine.

What We Heard

At the Resilient Institutions conference, academics, public servants, health-care practitioners, politicians and community organizations shared first-person accounts of working on the institutional front lines during the pandemic. The conversations took place under the Chatham House rule, meaning that information about the discussions can be shared but cannot be attributed to any speaker.

The following summarizes what we heard during the event. Each of the eight 90-minute roundtables included four to five speakers. (See Appendix B for the full program.)

The Roundtables

Public Health Decision-making During the Pandemic

This roundtable brought together individuals who played key public health roles. It examined how decisions were made, whether existing governance structures and processes were sufficient and how new ones were adopted. It also discussed what information is required for decision-making in a time of intense uncertainty and how the public should be engaged in these decisions.

A clear view was that the main institutions around public health decision-making within government generally worked as designed, although they were strained. Cabinets — federal and provincial — and supportive governance structures also worked as advertised, being able to make decisions within our system of responsible government. In all instances, however, governance had to adapt and be reconfigured to meet the volume, pace and scope of decision-making that was demanded. This also extended to the intergovernmental infrastructure around health care, such as health ministers’ and deputy ministers’ tables. All of these had to be supported by intense, daily engagement by public servants and ministers.

A key adjustment that governments had to make was to configure their decision-making processes to bring a “whole-of-government” approach in recognition that the pandemic was much more than just a public health issue. It touched the economy, schools and many other areas. There was a clear need for officials to work collaboratively across departments. This type of governance structure had to be put in place in many instances because it did not necessarily exist beforehand. At the federal level, a dedicated COVID-19 cabinet committee was created to co-ordinate the government’s response. Existing federal-provincial-territorial structures (such as the Conference of Deputy Ministers of Health) provided avenues for collaboration while governments at all levels set up various task tables and task forces to support rapid, focused decision-making.

However, institutions by themselves were no guarantee of success. It was necessary to adapt, reconfigure or set aside the usual rules and procedures to get things done quickly and effectively. Fostering strong interpersonal relationships within and across governments was incredibly helpful — a type of collaborative governance. Our permanent institutional structures did not anticipate the magnitude of the pandemic. The country was not prepared with adequate stockpiles (e.g., PPE, medical equipment and supplies, pharmaceuticals). On the other hand, through imagination and commitment, programs were developed and rolled out at an extraordinarily rapid pace.

We heard mixed reviews about the success of Canada’s health-care sector and institutions. Participants noted that Canada’s low mortality rates relative to other countries were likely due to its strict public health measures. That said, Canadian hospitals were already facing a capacity crisis prior to the pandemic and needed to respond in unprecedented ways when faced with a significant increase in new, critically ill patients. Measures such as hospital transfers were implemented to overcome capacity challenges. We also heard about pre-existing cracks in the long-term care systems, which contributed to the devastating outcomes that were experienced. On the scientific and research capacity side, we heard about the extraordinary conversations and information sharing that occurred between scientists and researchers globally. We also heard that the capacity of Canadian scientists to conduct clinical trials, which evaluate the effectiveness of health interventions, was limited by a poor information infrastructure with inadequate real-time access to insights and information.

First Nations communities faced low public health capacity and inadequate disaggregated data, as well as systemic biases that privileged Western conceptions of health and medicine. Some of these factors were overcome by developing culturally sensitive communications and interventions. However, it was noted that work should be done to ensure that governments and officials trust Indigenous communities more to understand and deliver for their membership, as well as have the necessary training and tools. One participant said:

“That capacity has to exist at several levels. . . . The providers who work in the community need more public health training. Education is huge. The middle band of decision-makers, policy analysts, health-care providers and others [need] to really understand because they’re blind [about] . . . how health care works in the First Nations community. It’s not something that people are trained to understand.”

We heard that future pandemic preparedness should determine how best to minimize public health impacts (e.g., morbidity and mortality) while also minimizing social and economic disruption. To achieve this, advisory structures must support integrated and co-ordinated thinking. Public health evidence was a central input for decision-makers during COVID. They also should have considered the broader scientific context as well as societal, economic and community impacts. However, advisory structures did not always enable this type of integrated thinking. It was recommended that models be gleaned from other jurisdictions. One participant reflected:

“I remember more than one cabinet minister saying: ‘Where does the integrated thinking, the integrated advice that brings together all of the considerations [take place]?’”

An additional consideration is the extent to which the advisory function inside governments should retain independence from the decision-making and implementation functions when establishing public health advisory relationships and structures. We heard that the role of independent advisers — who may feed evidence and speak independently about the impact of a policy — is different from the role of government policy implementers. Both need to work together symbiotically, but there also needs to be clarity about the distinction between them.

Participants discussed how challenging it was to share messages about public health decisions and build public trust. Canadians heard from so many different voices and received a huge volume of often complex information. Decision-makers were also dealing with anxiety within certain communities, as well as growing misinformation and disinformation. Embedding a communication specialist within scientific or public health teams was suggested as one means of improving communication with the public.

Data Production and Data Sharing in the Canadian Health-care System

The pandemic highlighted the crucial role that data play in informing health-care decisions and how imperative it is that we improve the sharing and use of data across Canada. This roundtable brought together experts to identify how we can better collaborate on this issue across levels of government. It included policy leaders with insights into Canada’s current challenges surrounding data sharing.

A key message was that Canada’s data collection processes and mechanisms are not equipped for real-time data flow. We heard that improving data flow should be a priority during the development phase of data systems so that structures can be built with this priority in mind, recognizing that it did not happen when these systems were built in the past. One participant characterized the current data structure in Canada as “towns or cities with no highways or infrastructure to connect them.”

This was especially problematic during the pandemic because of issues such as where to distribute vaccines, PPE and health-care human resources. These issues required quick decisions, but leaders did not have access to data to determine where resources were best utilized and to determine the results of diverting resources to certain communities. Panellists noted that Canada’s existing data systems are designed to track long-term changes or review results after a crisis has ended. Additionally, because of the lack of interoperability, spotting patterns in the existing data and forming a real picture of the situation in Canada is challenging. As one participant pointed out, you cannot take proactive actions to address emerging issues if you cannot see that those issues are emerging. The panellists stressed that the cost of not having these real-time data flows must be made clear to Canadians. There is also a lack of capacity to understand data and translate them into useful information, as well as challenging issues with recruiting people to build this capacity.

The panellists proposed several reasons why Canada’s failures in data sharing at all levels of government have endured since SARS, including technological complexities surrounding the infrastructure that exists to share data and the regulatory disentangling that needs to be done. For example, there are no standards surrounding data governance that have been universally accepted. Panellists identified one of the main issues in data sharing as confusion around data privacy legislation or a reluctance to share data that are hidden under the guise of adhering to privacy legislation. Several panellists argued that privacy concerns are largely a red herring and that there are many avenues to ensure there are checks and balances. One noted:

“We cannot have institutions, organizations, levels of government that are using the notion of a data steward to essentially hold data from actually getting to where it needs to [go] so that we can get at the insights in a real-time, consumable fashion.”

Panellists ultimately argued that these constraints would be largely solvable if not for the culture of information guarding and risk aversion that prevents information from getting where it needs to go. For example, there’s a nervousness among provincial governments about possible misuse of the data. One panellist said:

“It’s a real double-edged sword for them. Data can be weaponized [against] them. They’re nervous about this because often it’s used in a politicized way.”

However, the flow of these data is crucial to the flow of benefits. Panellists argued that Canada must ensure those benefits are distributed among different levels of government and stakeholders. The culture of hoarding such information must be changed. One participant suggested an independent body, such as the Canadian Institute for Health Information, could keep track of data gaps in the system, improving transparency around which provinces and territories are sharing data and which are not.

Another aspect of data sharing that panellists noted was disaggregated data. Decision-makers need to understand which socio-economic characteristics impact a successful outcome and identify patterns to adjust policies accordingly. Panellists challenged the idea that the current system of data serves everyone equitably or fairly. They noted that holding onto this notion can contribute to gaps in our system. The expertise necessary to challenge enduring inequities does not exist internally. Questions arise in communities that have been harmed by governments in the past about how to build trust. Trust is needed to obtain data from individuals on elements such as race, occupation, postal code, education, etc. Disaggregated data are essential because they can reveal how crises have impacted their health and socio-economic outcomes.

One panellist mentioned that the push for disaggregated data came from Black and Indigenous communities that understand the importance of being able to measure outcomes. Good data governance can be a mechanism to build trusting relationships with people who have been systematically disenfranchised, thus ensuring their participation, as well as transparency and accountability. An example of trust-oriented data collection could be the recognition of the unique constitutional status of First Nations, Métis and Inuit people, and the acknowledgment of Indigenous data sovereignty rights and principles through bilateral information-sharing agreements at both local and national levels.

Intergovernmental Relations During the Pandemic

The pandemic marked one of the most intense periods of intergovernmental relations in Canada’s history. This roundtable sought to provide a deeper understanding of the challenges and opportunities in this area in times of crisis. In addition, the panel considered how Canadian governments can implement those aspects of intergovernmental relations that worked well during COVID to improve our response to future crises. This roundtable included policy leaders with insights into the evolution and state of intergovernmental relationships during the pandemic.

There were diverse views on whether intergovernmental relations facilitated or inhibited the pandemic response. Most panellists agreed that the degree of communication between the different levels of government was high when the coronavirus first emerged. However, a key insight we heard was that, after the initial period of togetherness, there was significant variance in the amount of communication, and consequently the degree of co-ordination, between different levels of government.

We heard that relationships between some municipal governments and their provincial counterparts were frustrating, with municipalities expected to implement many provincial programs with little direction or notice from the province. Municipalities also faced significant revenue reductions and consequently had to lay off public servants despite having an elevated workload. Because information exchanges did not happen consistently between municipalities and the provinces, many municipalities turned to each other, both domestically and internationally, using established forums to facilitate information exchange that shaped their policy response. One participant gave a surprising insight into how minimal the dialogue really was by noting that one premier communicated with that province’s big city mayor only once throughout the entire pandemic. Another viewpoint raised by panellists was that a certain level of friction was to be expected, given that all levels of government were in crisis mode. Therefore, the exclusion of some governments from certain conversations may not have been intentional, but rather done out of a desire to get policy out the door quickly. One participant noted:

“When I was talking to some colleagues, it really felt that we were cut out even though we were delivering all the services on the ground.”

Similarly, Indigenous leaders trying to secure PPE and vaccines for their communities were frustrated by poor information sharing from other levels of government. However, once the dialogue began, Indigenous leaders were able to relay their policy solutions and logistical plans. They just needed a partner at the decision-making table to facilitate the implementation of those plans. This experience communicated a key lesson: that the exclusion of Indigenous leaders from the decision-making process during COVID was a product of a relationship allowed to erode over centuries. It is paramount to build that relationship on an ongoing basis. Panellists heard that in future emergency management planning, Canada must be more inclusive from the start on the role of Indigenous leadership and governments.

The experience of both municipal governments and Indigenous governments was indicative of tensions surrounding the question of jurisdiction, such as: Who does what? Who pays for what? One panellist mentioned the stark difference between cities that were “bleeding money” and provincial governments announcing surplus budgets, as well as the resentment that was thus created. Provinces and territories faced similar tension with the federal government because many costly services such as health care and infrastructure are largely the responsibility of the provinces, which have less ability to generate revenue than the federal government.

There were some triumphs. The federal government was very proactive at reaching out to large municipal governments and fought to bring provinces to the table when necessary. It was also more willing than usual to leave rules, practices, jurisdictions and procedures at the door and orient itself into a configuration best equipped to address the issue at hand. A shared goal across actors was a powerful avenue for breaking down institutional hurdles to collaboration. One participant noted that there were weekly first ministers’ meetings throughout a significant part of the pandemic, which was unprecedented.

At first, provincial and territorial governments reached out to each other for information sharing and exchanging best practices, but this communication diminished after the initial crisis phase had passed. There was little incentive on everyone’s part to maintain these relationships. One participant noted that the return to pre-pandemic levels of communication was not cause for concern because maintaining these crisis-phase relationships is resource-intensive and those resources can be better delegated elsewhere when not in an emergency. The challenge is figuring out what COVID-era processes should become permanent and what can be retired. There may be an instinct to retreat into pre-COVID practices, but governments need to review systems and see what should be preserved. A good start would be to look back at decision-making processes and see how agility can be improved in the long term. One participant said:

“There are improvements that can be made. I think the instinct is to kind of retreat back post-crisis into regular operations. Frankly, when people are exhausted, they kind of feel: ‘Ok, now I can sort of get back to my regular thing.’ [Instead] we’ve got to actually think about a systems review . . . to be able to take those lessons learned.”

A final point of discussion was whether we need new institutions or to keep existing institutions working as they should. One panellist proposed the revival of a federal minister of state for urban affairs to rectify some of the isolation that municipalities felt during the pandemic. Other panellists felt that it would be better to focus efforts on bringing municipalities and Indigenous governments to the intergovernmental forums that already exist. They argued the system would be better served by improvements to its existing structure, rather than the creation of something different.

Imagining a Federal Community That Works