The Growing Influence of Provinces in Canada’s Trade Negotiations

Introduction

The involvement of Canadian provinces in the process of negotiating international trade agreements has increased to such an extent that some observers have suggested this has become a “de facto shared jurisdiction” (Skogstad, 2012, p. 204). Two factors account for this trend.

Firstly, from a legal standpoint, while the federal government can negotiate international agreements in areas of provincial jurisdiction, it cannot legislate in those areas to implement the agreements it has made. Since international treaties are not automatically enforced under Canada’s legal system, their application requires legislative action by the relevant level of government, making provincial involvement imperative.

Secondly, so-called “new generation” agreements increasingly deal with issues that are sensitive for the provinces, such as provincial and municipal procurement, services, diversity of cultural expression voices and discoverability of cultural products on major digital platforms such as Spotify and Netflix, business subsidies, language policies, agriculture and supply management, labour mobility, the environment and climate change. In this context, the provinces are aware that their ability to exercise their constitutional powers, and therefore to legislate in certain areas, increasingly depends on the outcomes of trade negotiations. As a result, some provinces are seeking to be included in the multilevel dynamics of trade talks.

This article examines the foundations, modalities and channels of influence exercised by the provinces in Canada’s trade negotiations. Provinces have two main channels through which they can influence trade talks: international and intergovernmental mechanisms. Intergovernmental channels have lent Canada’s provinces growing influence in trade negotiations, to the point where their involvement has become essential.

I will begin by discussing the provinces’ international strategies and then look at Canada’s intergovernmental mechanisms in greater detail, focusing on five emblematic cases: the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement (FTA), the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with the United States and Mexico, the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) with the European Union, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the renegotiation of NAFTA, now known as the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA), under the first Trump administration. This comparison will examine a number of factors falling into two general categories: 1) the provinces’ involvement in defining the negotiating mandate, their presence at the negotiating table, their access to the draft texts, and federal-provincial consultation mechanisms; and 2) the provinces’ role in the final decisions and the treaties’ effects on their constitutional jurisdictions.

This analysis is based on nearly 20 years of research into trade negotiations involving Canadian provinces. It is a detailed synthesis of my previous work, including empirical research published in 2017, 2020 and 2022. During this time, I conducted a hundred interviews with political figures and civil servants who were directly involved in the negotiation processes, from the federal government and from several provinces, including Quebec and Ontario. The interviews reported here are drawn from these previous publications.

International channels

Canada’s provinces have a long history of involvement in international trade issues. While their first forays into external trade relations date back more than 150 years, it was in the 1960s and 1970s that they began to significantly increase their institutional capacity with respect to international relations.

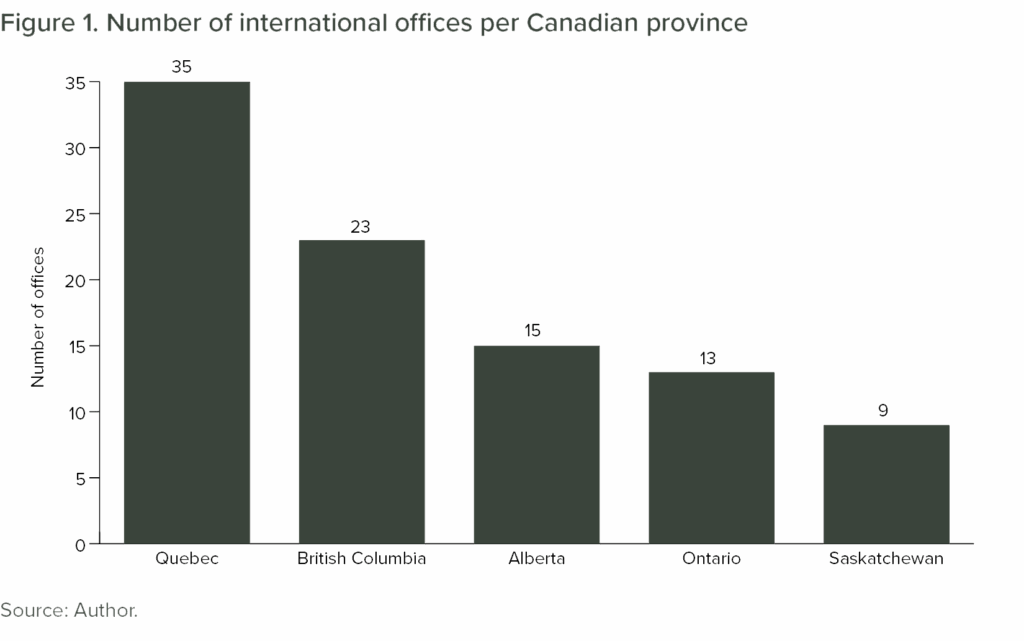

By the end of the 1970s, seven provinces had established more than 35 foreign delegations across three continents. Today, five Canadian provinces maintain 95 international offices (see Figure 1). The 170 per cent increase reflects an organized strategy of “trade paradiplomacy,” which is now the most developed component of the international relations efforts of Canadian provinces. Their offices perform a variety of functions, ranging from supporting businesses in seeking strategic partnerships to providing institutional representation (Paquin, forthcoming).

Several Canadian provinces have also signed a large number of international agreements with foreign partners that are directly or indirectly related to international trade (Grant, 2020). The case of Quebec is particularly revealing. Of the hundreds of international agreements signed by the Quebec government since 1965, approximately 43 per cent relate to areas such as economic development, agriculture, culture, natural resources, labour and securities (Ouellet & Beaumier, 2016, p. 71). Among the most notable are the 2001 agreement on public procurement with New York State, the 2008 Québec-France agreement on mutual recognition of professional qualifications, and the 2013 carbon market agreement with the State of California, which created the world’s second-largest carbon trading market at the time (Ouellet & Beaumier, 2016, p. 73). Although the Canadian government maintains that these agreements are not binding under public international law, some foreign partners, such as France, consider them to have legal force (Grant, 2020, p. 151).

During the CETA process from 2009 to 2016, several Canadian provinces, particularly Quebec under Jean Charest, actively sought to influence European bodies, both before and during the negotiations. Quebec’s delegate general in Brussels, Christos Sirros, played a key diplomatic role from the outset. In 2006, Sirros met with European Commissioner for Trade Peter Mandelson at a reception hosted by Jeremy Kinsman, the Canadian ambassador to the European Union (EU), to discuss the possibility of resuming trade talks between Canada and the EU. Subsequently, Quebec and Ontario stepped up joint efforts to make EU institutions and trade policymakers aware of their interest in a free trade agreement, particularly in 2007 and 2008. It was against this backdrop that Quebec Premier Jean Charest met German Chancellor Angela Merkel at the World Economic Forum in Davos in 2007. The following year, he convinced French President Nicolas Sarkozy, who held the rotating presidency of the Council of the European Union at the time, to officially support the opening of trade negotiations with Canada. Sarkozy subsequently became one of CETA’s most ardent European supporters (Paquin, 2017, 2020).

According to a senior federal source, “Jean Charest played a decisive role in restarting trade negotiations with Europe.” His efforts were met with caution in Ottawa; some senior officials perceived them as a threat to the federal government’s monopoly on international negotiations. Nevertheless, Charest increased the pressure by concluding a bilateral agreement on mutual recognition of professional qualifications with France in 2008, which foreshadowed some provisions of CETA. This move helped make provincial involvement in the negotiation process unavoidable. During the talks, the Quebec government remained actively engaged. Its chief negotiator, Pierre Marc Johnson, held numerous bilateral meetings with Mauro Petriccione, the EU’s chief negotiator (Johnson et al., 2015, p. 30). According to Paul Magnette, the Minister-President of Wallonia and the leading opponent of CETA in Europe, French President François Hollande was in favour of the agreement precisely because it was seen as the result of a joint initiative by France and Quebec (Magnette, 2017).

Canadian provinces have also leveraged other international channels to influence the outcome of international trade negotiations. This was particularly evident during the CUSMA negotiations, beginning in October 2017. The federal government under Justin Trudeau explicitly sought the active participation of provincial premiers, urging them to exert direct pressure on U.S. governors and influential American lobbies in order to build consensus in favour of maintaining North American free trade.

Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne was notable for her sustained diplomatic engagement. She met with no fewer than 37 state governors to defend Canada’s trade interests during the months following Trump’s election as president in the fall of 2016. Quebec government representatives made similar efforts. To maintain a consistent Canadian position, Ottawa established a co-ordinating mechanism with provincial and territorial governments. Among other things, the federal government shared talking points in order to harmonize the strategic communications of all Canadian stakeholders throughout the renegotiation process (Paquin & Marquis, 2022).

More recently, Canadian provinces have adopted economic retaliatory measures. With Donald Trump’s return to power, Ontario Premier Doug Ford has increased his media presence in the United States As chair of the Council of the Federation, he led a joint delegation of provincial and territorial premiers to Washington in February 2025 and secured a meeting at the White House with senior Trump administration officials. At the same time, several provinces introduced targeted trade sanctions in response to the Trump administration’s tariffs. For example, the Ontario government imposed a surcharge on electricity exports to the United States, barred U.S. companies from provincial public tenders, and urged Ontario municipalities to follow suit. It also terminated a $100-million contract with Starlink, the satellite internet service provider founded by Elon Musk. In a symbolic but significant move, state-owned corporations such as the Liquor Control Board of Ontario (LCBO) and the Société des alcools du Québec (SAQ) removed U.S. alcoholic beverages from their shelves, in direct violation of CUSMA.

Provincial participation is negotiated on a case-by-case basis

Since the end of the Second World War, Canadian trade policy has been developed mainly within the framework of multilateral negotiations under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Until the early 1970s, these talks were essentially about issues under federal jurisdiction, particularly lowering tariffs. It was therefore unnecessary to involve the provinces. A marked change began, however, with the Tokyo Round, which stretched from 1973 to 1979, when the multilateral trade negotiations turned to non-tariff barriers, touching on areas under provincial jurisdiction.

Consequently, the federal government gradually introduced various consultation mechanisms to inform the provinces of Canada’s international trade initiatives. The objective was to ensure the implementation of Canada’s commitments in areas under provincial jurisdiction.

However, since that time, Ottawa has been reluctant to formally include provincial representatives in the Canadian delegation. In the absence of a federal-provincial agreement in this area, provincial participation in negotiations remains variable and is negotiated on a case-by-case basis (Paquin, 2017). Figure 2 shows the main trade agreements discussed in this essay as well as the time allocated for preliminary negotiations.

Defining the negotiating mandate, the presence of the provinces at the table and consultation mechanisms

Theoretically, the federal government is responsible for leading Canada’s international trade negotiations, even when they relate to areas of provincial jurisdiction under the Constitution. These negotiations are often preceded or accompanied by intergovernmental discussions involving senior officials, and sometimes ministers and provincial premiers, to achieve a degree of co-ordination. That said, the process is entirely controlled by the federal administration, under the political direction of the Cabinet and the minister responsible for international trade. Provincial and territorial governments do not formally participate in this process, unless they are invited to do so by the federal government, as was the case with CETA.

The Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement and the North American Free Trade Agreement

Under the Brian Mulroney government, Canada adopted a more co-operative approach to federalism than had Pierre Elliott Trudeau, opening the door to greater provincial involvement in international affairs. Nevertheless, during the FTA negotiations with the United States, control of the formal negotiation process remained in Ottawa’s hands. The federal government appointed the chief negotiator, Simon Reisman, and defined Canada’s priorities. The provinces were not consulted on the mandate or invited to the negotiating table.

A standing committee on trade negotiations including representatives from the 10 provinces was established to oversee the negotiations. Prime Minister Mulroney also held 14 bilateral meetings with his provincial counterparts during the talks (Doern & Tomlin, 1991). Some provinces, such as Ontario and Quebec, recruited their own experts in order to increase their influence — Bob Latimer, a former senior federal official, for Ontario, and Jake Warren, a former Canadian negotiator in the Tokyo Round, for Quebec (Hart et al., 1994).

Although they were officially excluded from the process, the provinces were able to defend their interests through side channels. Sectoral working groups were created to consult them on certain issues. These mechanisms enabled more detailed technical co-ordination without undermining the federal government’s monopoly on international negotiations.

The dynamic seen during the FTA negotiations was repeated with NAFTA. The federal-provincial Committee for North American Free Trade Negotiations (CNAFTN) provided the provinces with partial access to working documents and a regular forum for voicing their concerns. These consultative structures were then institutionalized in the form of quarterly meetings of the Committee on Trade (C-Trade), where federal, provincial and now territorial representatives discuss Canadian trade policy. While C-Trade is still an advisory body, it has become one of the main channels for intergovernmental dialogue on trade (Paquin, 2017).

The Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement

The Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) was an unprecedented case in Canadian trade history. For the first time, the provinces were formally and regularly included in a trade negotiation delegation — not at the initiative of the federal government but in response to an explicit request from the EU. Having learned from past failures, the EU made provincial involvement a condition for entering into negotiations, given the provinces’ jurisdiction over key areas such as services and public procurement (Paquin, 2020).

While some senior Canadian officials claimed the federal government had made this decision on its own initiative, correspondence between Stockwell Day, Minister of International Trade in the Harper government, and Quebec Premier Jean Charest clearly indicates that the EU had explicitly demanded the inclusion of the provinces. Day wrote:

[translation] As you know, the European Commission and Member States have sought assurances that Canada wishes to negotiate an ambitious agreement and that the provinces and territories will remain fully engaged in the process …. The EU’s concerns about the level of provincial and territorial involvement stem from the fact that many European interests fall (in whole or in part) within provincial or territorial jurisdiction, including services and public procurement …. [W]e will work with the provincial and territorial governments to develop Canada’s negotiating mandate so that the interests of the provinces and territories are taken into account in Canada’s position. This will require communication with provincial and territorial representatives before and after each meeting with the EU. Finally, provincial and territorial representatives will participate, as full members of the Canadian delegation, in negotiation sessions dealing in whole or in part with matters within their areas of jurisdiction, and we expect [them to have] the authority to make binding commitments in those areas. (Letter from Stockwell Day to Jean Charest, February 18, 2009)

The provinces played a significant role in the CETA negotiations: they were involved in developing the negotiating mandate and the joint report, had access to the draft texts, could submit strategic memoranda, and attended more than 275 meetings. Quebec was particularly active, submitting more than 150 position papers (Paquin, 2022).

In practical terms, provincial representatives could not intervene directly in the formal negotiations, but they were in the room and could pass notes, request that a session be suspended and indirectly influence the federal position. They therefore played an advisory and strategic role. Their influence was strengthened by the informal relationships they formed with European negotiators.

However, while provincial participation has increased, international treaty negotiations remain an exclusively federal jurisdiction. In retrospect, the CETA experience appears more an exception than a structural turning point. The provinces have not been invited to the table for the negotiation of subsequent agreements, such as the CPTPP and CUSMA.

The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership

Provincial participation in the negotiations on the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership was much more limited than in the case of CETA. The CPTPP evolved from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, an agreement initially negotiated by 12 countries, including the United States, which was revamped after the Trump administration pulled the U.S. out in January 2017. The remaining 11 countries, including Canada, signed the new agreement on March 8, 2018, in Santiago, Chile. Canada joined the talks only in 2012, nearly four years after they began, in a defensive posture, with the main objective of not being excluded from the deal. This stance influenced the scoping process and the drafting of the negotiating mandate; little thought was given to including the provinces.

In contrast to the CETA process, provincial participation was never raised as a condition or expectation by other countries. The model of active provincial involvement established during the CETA negotiations was not replicated. The provinces were not consulted on their offensive or defensive interests before Canada entered the talks and weren’t in the room for the negotiations. According to a Quebec government representative, no province appointed an external “chief negotiator.”

Canadian intergovernmental mechanisms were confined to C-Trade meetings and post-round briefing sessions. According to Quebec and Ontario government representatives, these meetings consisted mainly of one-way transmission of information, often voluminous and delivered at the last minute, leaving little time for the provinces to analyze it. An Ontario official described the process as a “data dump,” suggesting that the objective was more to satisfy a consultation requirement than to allow for meaningful provincial input (Paquin, 2022).

Despite their limited formal inclusion, the provinces were able to draw on some aspects of the CETA experience. According to a Quebec representative, provincial participation consisted of two components: the provinces were on-site to attend briefing sessions and maintain a strategic watch, and they regularly sent memos stating their positions. Unlike with CETA, however, the draft texts were received too late to allow for in-depth analysis or an informed response.

The absence of strong political leadership, such as that provided by Jean Charest during the CETA negotiations from 2008 until his election defeat in September 2012, also contributed to Quebec’s more modest involvement. None of Charest’s successors showed the same interest in securing a greater role for the provinces. Informal co-ordination did continue, however, as evidenced by letters sent by Quebec ministers to their federal counterparts prior to some negotiating sessions, particularly on agricultural issues.

Overall, the CPTPP represents a return to the default setting for federal-provincial relations with respect to trade, far removed from the structured, co-operative model of CETA. This episode underscores the lack of an institutionalized framework guaranteeing provincial participation; each new round of negotiations requires an implicit renegotiation of the role of the provinces.

The Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement

The renegotiation of NAFTA that produced the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement was of keen interest to Canada’s provinces. Unlike the previous FTA and NAFTA negotiations, no province opposed the renegotiation. All recognized the strategic importance of preserving access to the U.S. market, the main trading partner of every province.

In this context, the federal government adopted a “progressive” or “inclusive” approach aimed at strengthening the clauses on labour standards and environmental protections, and adding new chapters on gender equality and Indigenous peoples. The United States made a number of demands relating to areas entirely or partially under provincial jurisdiction, such as agriculture, government procurement, the sale of wine and spirits, services, investment, e-commerce and certain key industries such as automotive, chemicals, steel and aluminum.

Several provinces appointed chief negotiators and recruited special advisers. Ontario appointed a senior civil servant as chief negotiator and enlisted the help of John Gero, former Canadian ambassador to the World Trade Organization, as a special adviser. Quebec continued the strategy initiated under Jean Charest by appointing an external chief negotiator, former Finance Minister Raymond Bachand (Paquin, 2022).

However, co-operation between federal and provincial negotiators did not follow the same path as during the CETA negotiations. In the NAFTA renegotiation, the federal government explicitly rejected the Quebec government’s request for access to the negotiating table.

The federal team frequently consulted the provincial teams in special meetings devoted to the renegotiation, which dealt with much more specific topics than those addressed at the regular C-Trade meetings. The provinces attended daily information meetings on the day’s progress throughout the negotiations. Because of the volume of information required for the renegotiation of NAFTA, C-Trade meetings were replaced by separate meetings specifically devoted to the talks. The provinces were not only consulted but invited to express their views — which were taken into account, according to the Ontario and Quebec representatives. They also attended several strategic meetings prior to the negotiation rounds, as well as monthly briefing sessions. Provinces with specific interests had good access to the officials responsible for negotiating the relevant chapters.

While the provinces were not represented on the Canadian delegation during the renegotiation of NAFTA, they exercised considerable influence. According to Frédéric Legendre and Laurie Durel, two Quebec government officials who worked on trade issues, more than 300 Quebec civil servants were directly involved in preparing analyses and positions on the issues raised by the negotiations. Legendre and Durel described Quebec’s input into the negotiations as follows:

[translation] Quebec’s comments to the Canadian federal government regarding the texts under negotiation led to changes to the text of several chapters of the agreement, including on topics that one might not naturally associate with Quebec, such as the side letter on energy and the chapter on digital trade. (Legendre & Durel, 2022, p. 54)

At the end of each round, the federal government provided provincial representatives with updated versions of the negotiated texts. Ontario and Quebec could see the points on which the parties had agreed and the parties’ proposals on outstanding issues. The representatives of the Ontario and Quebec governments analyzed each new version of the texts in depth. They had the opportunity to discuss the progress of the negotiations with the chief negotiators and their teams and to provide comments and analyses.

Participating in the NAFTA renegotiation rounds provided representatives from Quebec, Ontario and several other Canadian provinces with important opportunities to meet with: 1) the federal negotiators to discuss provincial interests; 2) stakeholders from various sectors (e.g., agriculture, automotive and pharmaceuticals); and 3) representatives from other provinces with whom they could work on specific issues. Although no formal negotiation rounds took place after March 2018, Quebec and Ontario representatives remained in regular contact with the federal government, at both the administrative and political levels. Throughout the renegotiation process, each province also had a representative in Washington.

The provinces also met to discuss specific issues and prepare for the negotiation rounds. These meetings were fairly organic and informal; most often, they were held in conjunction with the negotiation rounds or at the initiative of the province chairing the Council of the Federation. For instance, discussions on modernizing NAFTA took place at the last Council of the Federation meeting in Alberta in July 2018 and on the sidelines of the NAFTA renegotiation round in Montreal in June 2018. Most provinces and territories were well represented by experienced teams. Table 1 shows provincial participation in the various stages of the negotiations.

Analysis of provincial participation in trade negotiations

The participation of Canadian provinces in international trade negotiations is evolving. While provincial involvement was long marginal, it has gradually increased as trade talks have come to touch on areas of provincial jurisdiction. As noted in the introduction, the constitutional powers of the provinces are increasingly affected by international trade negotiations. In a federation such as Canada, respect for the division of powers and democratic principles makes greater provincial participation in these processes entirely legitimate. If the federal government were to negotiate a trade agreement independently and then impose its implementation on the provinces by indirect means, it would be circumventing the limits on its powers — in other words, doing indirectly what it does not have the power to do directly. Therefore, provincial involvement at a certain stage of trade negotiations is not only desirable but inevitable to preserve the federation’s balance. The most notable example of provincial participation remains the inclusion of the provinces in the Canadian delegation during the CETA negotiations, a development that has often been cited as a milestone in the history of Canadian federalism.

The implementation of the major free trade agreements is a particularly revealing aspect of provincial participation in trade negotiations. Of the five major trade agreements signed by Canada, only CETA required significant legislative changes in areas of provincial jurisdiction to align the provinces’ legal frameworks with the treaty commitments. These changes included adjustments to public procurement rules, professional regulation and technical standards, all of which are constitutionally provincial responsibilities.

This is significant for two reasons. First, it shows that, the more ambitious a trade agreement is, the more likely it is to encroach on provincial jurisdiction. Secondly, it highlights the importance, if not the necessity, of involving provincial governments before the negotiation process begins, not just at the implementation stage. Their inclusion not only avoids subsequent legal and political friction but also enhances the democratic legitimacy of the agreement by ensuring that it takes into account the economic, social and regulatory realities of each province.

In the case of CETA, the active participation of the provinces at the negotiating table was seen as an important step forward for co-operative federalism in Canada. It made it possible to anticipate the necessary legislative adjustments, secure the political support of provincial governments and reduce the risk of challenges or blockages during implementation of the agreement.

This precedent suggests that the scope of future Canadian trade agreements (and any other kind of agreement) could be limited if the provinces are not included in the process from the outset. Conversely, their structured involvement from the early stages of negotiations supports the development of more comprehensive and coherent agreements that are better integrated into the fabric of Canadian federalism.

In other words, the inclusion of the provinces should be regarded not as an obstacle but rather as a condition for the success of agreements that affect shared or exclusively provincial areas of jurisdiction. It not only strengthens the internal consistency of Canada’s commitments but also its international credibility as a federal state capable of marshalling its various levels of government behind shared trade objectives.

However, the CETA experience remains unique. The participatory model used during the CETA negotiations was not institutionalized or systematically replicated in subsequent negotiations (even if we include other negotiations not discussed in this article). In the federal government’s view, existing structures such as C-Trade have become more effective over time, allowing for better circulation of information and closer co-ordination. This improvement in processes means that a major overhaul of the institutional framework is not necessary to sustain intergovernmental relations. Many federal officials argue that this forum ensures adequate consultation with the provinces.

However, this view is far from unanimous. Provincial governments, particularly Quebec and Ontario, are critical of C-Trade. They often consider the time allowed for feedback too short to allow for serious internal consultations among provincial government departments.

The provinces are not blameless. Many lack the resources to analyze trade negotiations. In addition, provincial premiers often take little interest in them. To address this structural problem and ensure better consideration of provincial perspectives in negotiations, the Council of the Federation could play a more significant role. This body could bring together and share the expertise of different provincial civil services and even provide analysis of ongoing trade negotiations. The Council could also establish links with provincial delegations abroad, which enable the provinces to identify barriers to market access elsewhere in the world, to develop a better understanding of international trade issues and to support concerted action in defending the country’s economic interests. Exchanges of civil servants between the federal and provincial governments could also be contemplated to promote the creation of a shared public space on these issues.

What would happen if the provinces didn’t agree on some elements of an agreement? Concluding a trade agreement is a delicate political process. Typically, negotiators swiftly reach agreement on non-controversial points while more contentious issues are reserved for the final stages of the negotiations, exacerbating tensions at the critical juncture. In all the cases discussed above, the conclusion of the agreement, denoted by Canada’s signature, and its subsequent ratification are the exclusive responsibility of the federal government. The final decisions in every case studied were made without the provinces being present.

In the case of CETA, despite the unprecedented inclusion of the provinces, only the federal negotiators remained at the table at the end of the discussions. The federal executive made all the final decisions, even when they directly affected the provinces. A federal negotiator explained it in these terms:

It’s true that the provinces were not at the table in the later stages of the CETA process. But I believe that for the most part, there were no outstanding issues of provincial jurisdiction. Market access for beef, pork and cheese, intellectual property and the investor-state mechanism are all under federal jurisdiction.

[…] It is also normal in a negotiation to have limited participation in the final stage of conclusion. Having a province at the table would give it a virtual veto, which would be unmanageable and could jeopardize an agreement “for the greater good of Canada.” (Paquin, 2022)

The situation was the same at the end of the CUSMA negotiations: the federal government was responsible for all the final decisions. All decisions on sensitive issues were therefore made at the federal departmental level or higher, without direct input from the provinces. During the final weeks of the NAFTA renegotiation, there were fewer opportunities for federal, provincial and territorial officials to meet. After the seventh round in April 2018, the negotiations were conducted mainly by ministers and chief negotiators from the three NAFTA countries.

On August 27, 2018, the United States and Mexico reached a bilateral agreement. The U.S. government then exerted maximum pressure on Canada to join the agreement. In August and September 2018, all the meetings were held in Washington, mainly between political decision-makers. With the September 30 deadline for submitting the text to Congress and ensuring its approval in time for signing by the outgoing Mexican president looming, the pace of discussions between Canada and the United States picked up. As a result, the provinces were allowed scant space; they were able to make few comments or even receive updates.

It should be noted that Canada was forced to renegotiate NAFTA under intense diplomatic pressure and the tight schedule for the talks — only 13 months compared with 8 years for CETA — made it impossible to replicate the participatory model adopted for CETA. Furthermore, Canada’s temporary exclusion from the bilateral talks between the United States and Mexico in the summer of 2018 produced an asymmetrical situation that has been described as “take it or leave it,” significantly reducing the federal government’s room to manoeuvre.

It is unlikely that more sustained consultation or greater inclusion of the provinces could have substantially altered the final outcome of the CUSMA negotiations. However, greater participation would have allowed the provinces to raise their concerns and given them better visibility on the compromises under consideration, which would have facilitated political acceptance of the deal. In Quebec, for example, the announcement of the agreement came on the eve of provincial elections in which supply management had been an issue. The lack of transparency and visibility therefore caused keen dissatisfaction in Ontario and Quebec.

Despite these tensions, the provinces ultimately supported ratification of CUSMA, which they saw as preferable to withdrawing from the trade agreement altogether. Rather than contesting it or demanding renegotiation, they quickly turned their attention to discussion of economic compensation from the federal government. Nevertheless, it seems clear that, if the provinces had been given a formal veto, the negotiations would have been considerably more difficult, if not impossible. It would, however, have forced the federal government to negotiate compensation in advance, even before the agreement was officially announced.

Conclusion

The coming months and years will be decisive for an assessment of the degree of co-operation between the federal government and the provinces in international trade negotiations. The current environment, dominated by the Trump administration’s deep hostility toward trade agreements in general and CUSMA in particular, is increasing the pressure on all Canadian stakeholders involved in defending the country’s economic interests.

In the summer of 2025, Mark Carney’s new government expressed its desire to conclude a trade and strategic agreement with the U.S. administration in order to lower the tariffs imposed by the Trump administration. According to available information, the provinces were consulted. Among other things, high-level meetings were held between Carney and the provincial premiers. This process is reminiscent of the dynamics seen during the negotiation of the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement in the 1980s.

The contacts at the top can be explained by the circumstances. The transition between the Trudeau and Carney governments, which began in early 2025, coincided with an intensification of the provinces’ diplomatic and trade efforts with U.S. authorities. Several provincial delegations were particularly active in Washington and U.S. state capitals on issues directly affecting their interests. Against this backdrop, marginalizing the provinces in the negotiation process became politically and institutionally difficult to justify.

Meanwhile, another important deadline is approaching: under Article 34.7 of CUSMA, a review of the agreement must be initiated by July 1, 2026. The three parties — Canada, the United States and Mexico — have already expressed their intention to conduct this renegotiation. This new round of negotiations therefore appears inevitable and brings the issue of provincial participation in trade discussions back to the forefront.

The management of Canadian federalism with respect to trade issues will be tested by this process. It can no longer be a matter of ad hoc or symbolic consultation of the provinces; the question now is determining to what extent their participation can be structured, institutionalized and incorporated into the development of negotiating mandates and positions. Unless this is recognized, there is a high risk of a widening gap between Canada’s constitutional reality and its trade diplomacy practices, which could undermine the implementation of future agreements and stir intergovernmental tensions.

The U.S. government’s known demands have the potential to divide the provinces. The 2025 report of the U.S. Trade Representative confirms their priorities: supply management in Ontario and Quebec (particularly for milk), cheese standards, tariff quotas and even provincial policies governing the sale of alcohol are described as barriers to trade. Other sensitive issues for relations with the provinces include the regulations in Bill 14 concerning French-language labeling in Quebec, supports for local culture, taxation of the digital giants, the Online Streaming Act (whose unilateral suspension by the Carney government is already drawing criticism), the rules of origin for Ontario’s automotive industry, and Alberta’s energy policy.

These negotiations will take place at a politically sensitive time, with Quebec elections scheduled for fall 2026 and a possible referendum on Alberta’s constitutional status. In an environment where international trade agreements are increasingly encroaching on provincial jurisdiction, a number of voices are calling for greater provincial autonomy in foreign affairs.

In Quebec, the 2024 report of the advisory committee on constitutional issues (Comité consultatif, 2024), which was praised by the Premier of Alberta and others, took this view. It recommended enshrining the Gérin-Lajoie doctrine in a formally codified Quebec constitution and unilaterally amending the Constitution Act, 1867 to explicitly recognize Quebec’s power to act on the international stage in its areas of jurisdiction.

It also suggested that Quebec’s accession to any international treaty should be conditional on its active participation in the negotiations as part of the Canadian delegation. Finally, the report recommended establishing a standing committee of the National Assembly on Quebec’s international relations. These are proposals that cannot be ignored by the federal government.

References

Comité consultatif sur les enjeux constitutionnels du Québec au sein de la fédération canadienne (Comité consultatif). (2024). Ambition. Affirmation. Action. Gouvernement du Québec.

https://cdn-contenu.quebec.ca/cdn-contenu/adm/min/justice/publications-adm/comites-consultatifs/ccecqfc/BOM_Rapport_Comite_consultatif_2024_vf.pdf

Doern, G. B., & Tomlin, B. W. (1991). Faith and fear: The free trade story. Stoddart.

Grant, T. (2020). Who can make treaties? Other subjects of international law. In D. B. Hollis (Ed.), The Oxford guide to treaties (pp. 150-172). Oxford University Press.

Hart, M., Dymond, B., & Robertson, C. (1994). Decision at midnight: Inside the Canada-US free-trade negotiations. UBC Press.

Johnson, P. M., Muzzi, P., & Bastien, V. (2015). Le Québec et l’AECG. In C. Deblock, J. Lebullenger, & S. Paquin (Eds.), Un nouveau pont sur l’Atlantique : l’Accord économique et commercial global entre l’Union européenne et le Canada (pp. 27-40). Presses de l’Université du Québec.

Legendre, F., & Durel, L. (2022). Le rôle du gouvernement du Québec dans les négociations d’accords de libre-échange : le cas de l’ACÉUM. Revue québécoise de droit international, special issue, March, 41-58.

Magnette, P. (2017). CETA, quand l’Europe déraille. Éditions Luc Pire.

Ouellet, R., & Beaumier, G. (2016). L’activité du Québec en matière de commerce international : de l’énonciation de la doctrine Gérin-Lajoie à la négociation de l’AECG. Revue québécoise de droit international, special issue, June, 67-79.

Paquin, S. (2017). Fédéralisme et négociations commerciales au Canada : l’ALE, l’AECG et le PTP comparés. Études internationales, 48(3-4), 347-369.

Paquin, S. (2020). L’affirmation des États fédérés dans les négociations commerciales internationales : le cas de l’Accord entre le Canada et l’Union européenne. Revue internationale de politique comparée, 27(1), 141-166.

Paquin, S. (2022). Means of influence, the joint-decision trap and multilevel trade negotiations: Ontario and Quebec and the renegotiation of NAFTA compared. Journal of World Trade, 56(5), 853-878.

Paquin, S. (forthcoming). Provincial state building in Canada and paradiplomacy: A comparative perspective. In L. Bernier & D. Latouche (Eds.), The notion of province-building: New perspectives on an old debate. University of Toronto Press.

Paquin, S., & Marquis, L. (2022). Gouvernance multiniveau et négociations commerciales : le rôle du Québec et de l’Ontario dans la renégociation de l’ALÉNA. Revue québécoise de droit international, special issue, March, 21-40.

Skogstad, G. (2012). International trade policy and Canadian federalism: A constructive tension? In H. Bakvis & G. Skogstad (Eds.), Canadian federalism (3rd ed., pp. 159-177). Oxford University Press.

The essay by Stéphane Paquin (PhD, Sciences Po Paris) looks at Canadian international trade from the perspective of the provinces, particularly their influence and leadership in the signing of international agreements. The author analyzes five international agreements to illustrate an inherent feature of the federation and its modes of governance: the complexity of the consultation mechanisms between Ottawa and the provinces. This essay explores in detail the provinces’ participation in various negotiations, their role in defining mandates and influencing the texts under negotiation, the effects of international treaties on the constitutional powers of the provinces and the federal government, and the work carried out by the provinces during final arbitration. As the United States loses its status as a privileged country for international trade, this essay offers an essential analysis of the risk now posed by the practice of trade democracy and the constitutional obligations of the provinces within the federation.

This essay was published as part of the series Barriers and Bridges: Rethinking Trade Within the Federation published under the direction of Valérie Lapointe by the Centre of Excellence on the Canadian Federation. Editorial co-ordination was done by Étienne Tremblay, proofreading by Zofia Laubitz and production and layout by Chantal Létourneau and Anne Tremblay.

This essay was translated from French by John Detre. It is also available in French under its original title L’influence grandissante des provinces dans les négociations commerciales du Canada. The original version was copy-edited by Étienne Tremblay.

Stéphane Paquin is a full professor at the École nationale d’administration publique (ENAP). He also holds the Jarislowsky Chair in Trust and Political Leadership at UQTR-ENAP. He was admitted to the Cercle d’excellence de l’Université du Québec in 2024 and has received several distinctions, including a Canada Research Chair in International and Comparative Political Economy and a Fulbright Chair at the State University of New York. His publications appear in academic journals such as the Journal of World Trade, New Political Economy, Politics and Governance, International Journal, The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, Canadian Journal of Political Science, Canadian Public Administration Journal and Études internationales.

To cite this document:

Paquin, S. (2025). The Growing Influence of Provinces in Canada’s Trade Negociations. Institute for Research on Public Policy.

The opinions expressed in this essay are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IRPP or its Board of Directors.

If you have questions about our publications, please contact irpp@irpp.org. If you would like to subscribe to our newsletter, IRPP News, please go to our website at irpp.org.

Cover: Luc Melanson