Reimagining Canada as Inter-National Understanding First Nations-Provincial Relationships

Les relations entre les peuples autochtones et les allochtones sont souvent considérées comme des interactions entre deux groupes distincts : le Canada et les peuples autochtones, ce qui simplifie les relations entre les deux groupes et occulte leur complexité. En outre, l’accent est souvent mis sur les relations avec le gouvernement fédéral. Pourtant, la plupart des interactions entre les gouvernements et les Autochtones se font au niveau provincial. Cette étude se penche sur ces interactions en rejetant l’idée qu’elles relèvent de la politique intérieure et d’une conciliation entre de simples parties prenantes. Il faut plutôt les considérer sous un angle diplomatique, comme des relations internationales où chaque acteur apporte son propre système de gouvernance et sa souveraineté. Comparer l’état actuel des relations entre les Premières Nations et les gouvernements provinciaux du Nouveau-Brunswick et de la Colombie-Britannique souligne comment les différentes conceptions de ces relations aboutissent à des pratiques gouvernementales différentes.

Introduction

In public policy analysis and commentary, Indigenous-settler relations are often considered as interactions between two singular groups: “Canada” and “Indigenous peoples.” This thinking flattens the relationships between them and obscures the complexity of both. The Indigenous peoples and nations upon which Canada is constructed are numerous, diverse, and culturally and politically distinct from one another. Prior to and since colonization, they have maintained complex relationships with one another, ranging from forms of coexistence to different modes of diplomacy. Settler Canada itself is also made up a diverse group of peoples from around the world governed by 10 provinces, three territories and a federal government, with the provinces and the federal government each maintaining distinct authority through their respective Crown. Each Crown exercises primacy over its domain and is bound to the others by complex relations of jurisdiction, law and diplomacy. The result is a country made up of overlapping structures of sovereignty and authority that, from a settler-colonial perspective, are organized into a unity through Confederation. However, appeals to this unity can mask the distinctiveness of political and treaty relationships, laws and applications of authority between different nations, ultimately homogenizing sovereignty in the hands of settlers. As such, we want to advance an inter-national reading of Canada as made up of governing relationships that are many, varied, connected and, crucially, occurring between and across multiple sovereign nations. For these relationships to work, settler governments must act in accordance with the sovereignty of Indigenous nations and reposition governance as a collective, rather than top-down, project.

Importantly, when it comes to relationships with Indigenous nations in Canada, it is the provincial governments (rather than the federal government) that are the actors implicated in many day-to-day aspects of governance and colonial policy. Indeed, featuring them in policy analysis is especially important because of the way they exercise authority on issues such as land and resource management. So, while federal-Indigenous relations draw much of the media’s attention, the number of governance interactions between provinces, First Nations, Inuit, and Métis governments may easily number in the hundreds to thousands. While they can make for a dizzying collection of issues and relationships, we aim to unravel and demystify the relationships between Indigenous nations and provinces, analyzing them and offering insights into current colonial systems and ways to think beyond them. We do so as settlers who believe these insights can be an effective pathway for improving relations. Understanding them is one step toward taking meaningful steps toward Indigenous self-determination, as outlined in the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP) report and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

Our analysis focuses on provincial policy, but also provincial authority and jurisdiction and, importantly, their relationship specifically to First Nations’[1] sovereignty. How should we understand these relationships? Are there existing models that we can use to illustrate how we see these relationships unfolding? To undertake our analysis, we use the understanding of the Crown itself as a land claim (Wood & Rossiter, 2020). That is, rather than a given fact, settler sovereignty needs to be continually remade and claimed against existing Indigenous sovereignty.[2] Canada’s own interpretations of treaty do not resolve this tension (Starblanket, 2019), especially in areas that are not covered by treaty — like much of British Columbia — and even in some that are — like New Brunswick. In jurisdictional terms, then, each province exercises authority only in relation to Indigenous sovereignty, even though settler power (financial and otherwise) often defines the terms of the relationship. Our goal is to provide an understanding of these tensions, and offer a vision of a collaborative, inter-national relationship not premised on settler authority and sovereignty.

To do this, we draw on international relations and diplomacy to think of Indigenous-provincial relations as a new form of paradiplomacy. Specifically, we approach paradiplomacy as a form of diplomatic engagement between polities not considered states under the Westphalian system.[3] Rather than suggesting a “lesser” form of authority, turning to a diplomatic lens and grounding it in existing theory allows us to (a) assess existing relationships between provinces and Indigenous nations; and (b) discuss mechanics of governance that can improve relationships. As we discuss, paradiplomatic relationships better capture Indigenous authority, and will produce better social, economic and political outcomes. Employing the frameworks of paradiplomacy and inter-nationalism allows us to analyze without prescribing a particular form of government or state structure onto Indigenous nations. While some nations have used — and continue to use — to use techniques and tools of state governance,[4] many have also been clear that they do not wish to operate exactly like states. Heeding this, paradiplomacy and inter-nationalism allow for longstanding governance mechanisms and models to remain in place and offer a vision of diplomatic practice outside of the Westphalian imaginary. Rather than suggesting that Indigenous nations are domestic (Canadian) entities, a paradiplomatic lens allows us to see Indigenous-provincial relations as encompassing two self-determining polities. Each nation maintains its own governance traditions and practices, but co-operation and efforts toward developing collaborative engagement offer opportunities for a shared future beyond colonial dynamics.

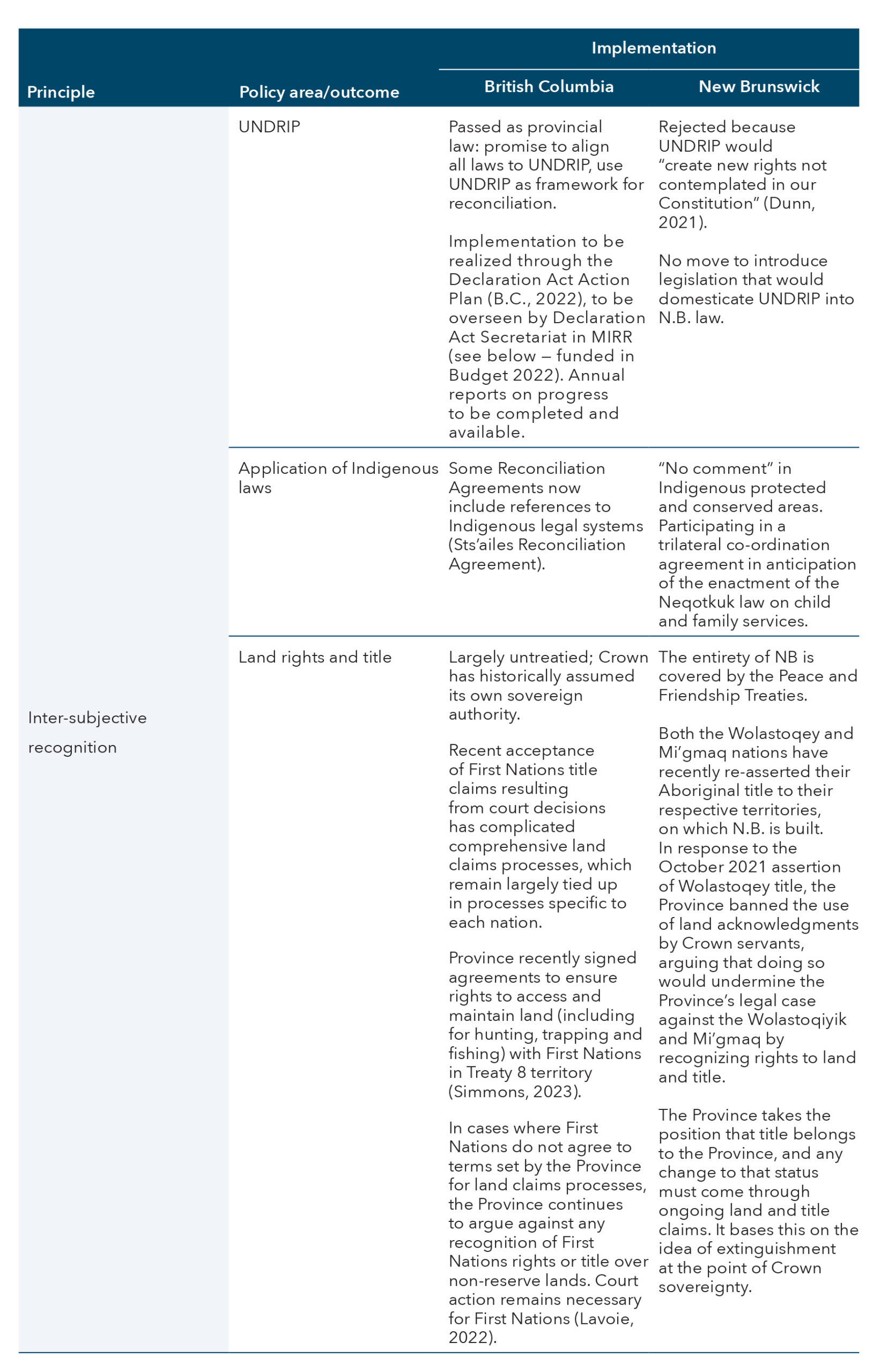

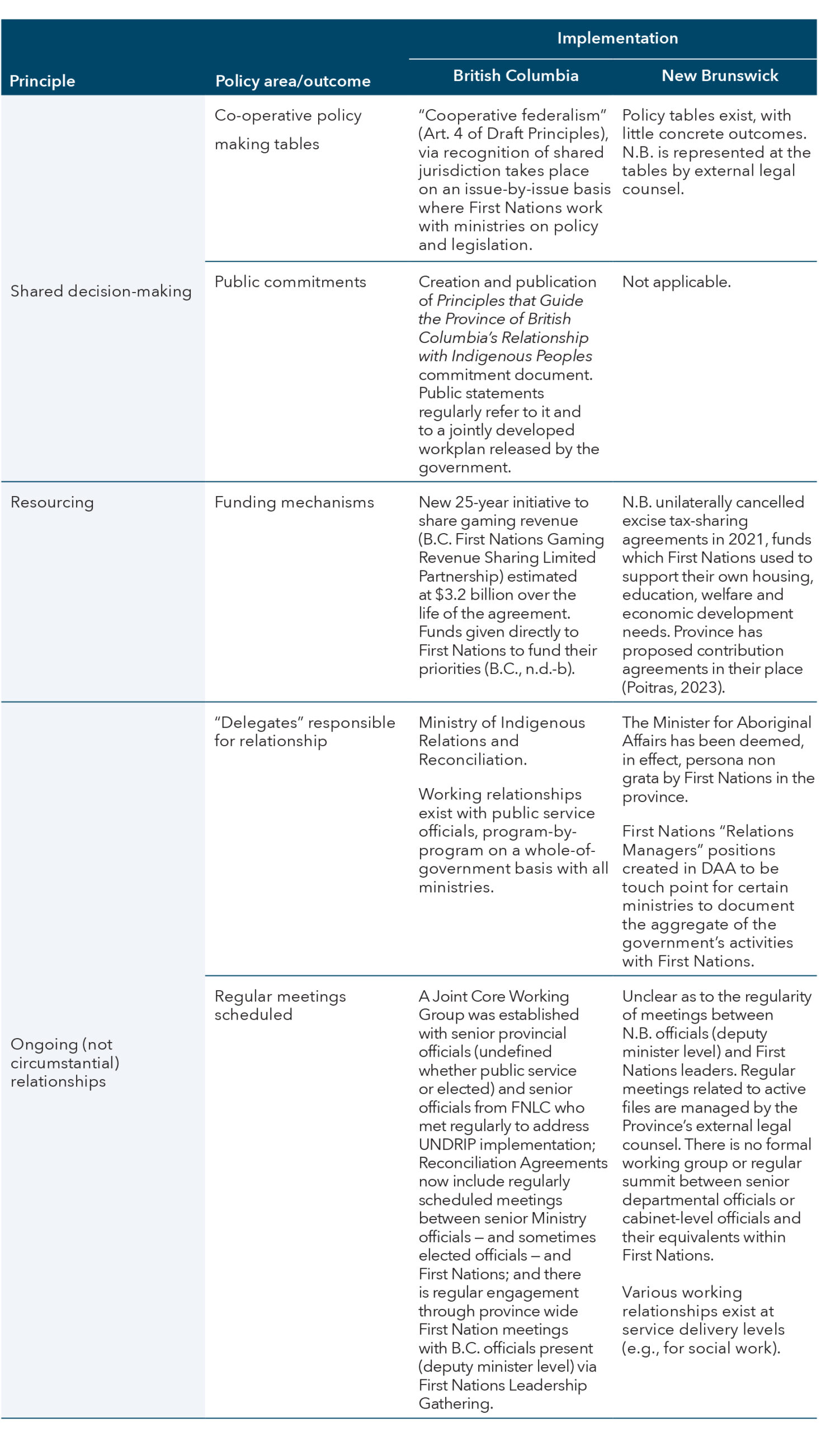

We make these assessments using two illustrative examples of provincial relationships with First Nations on the subject of UNDRIP and “reconciliation”: British Columbia (B.C.) and New Brunswick (N.B.). These cases represent two distinctive approaches to governance as it relates to First Nations-provincial relations. On one coast, B.C. has passed the UNDRIP and has declared its approach as one of including of Indigenous peoples in decision-making. On the other, N.B. has been open about its unwillingness to do the same, restricting co-operation to limited issues and actively antagonizing the major First Nations in the province. Our analysis highlights the inter-national aspects of both provinces, their tactics of colonization, and their understanding of the legal and constitutional frameworks within which they are enmeshed. We then discuss the possibility for different diplomatic encounters in provincial policy and suggest how these policy mechanisms could play out, as existing relationships operating through provincial jurisdiction reveal the ways that bureaucracies are fundamentally unprepared for engaging in diplomatic relationships with First Nations.

These cases illustrate that, although the provinces may practise reconciliation differently, the divergence is most striking in how they practise the symbolic politics of Indigenous-settler relations, and their colonial conceptions remain aligned across jurisdictions and Crowns. Ultimately, neither B.C. nor N.B. is willing to surrender authority. This creates major roadblocks to realizing a meaningful reconciliation, in which settler governments and Indigenous nations cohabit a shared space through shared, or at least mutually respectful, governance models.

Clashing Sovereignties?

The questions motivating us come down to the issue of authority: Who has it? How is it exercised? As such, we need to work with the concept of sovereignty. In a Eurocentric sense, it has come to mean the authority, or the decision-making power, over a specific population in a defined territory (Agnew, 1994). This is how the Canadian constitutional order understands sovereignty: each level of government and each provincial government has specific powers over particular policy areas, populations and lands that correspond with its attendant authorities stemming from their respective Crowns and that are not held by others. Sovereignty within Canada is therefore largely understood as being “exclusive” (Wildcat, 2020). For example, the provincial government in N.B. does not govern for the residents of B.C. Here, we focus on how provincial power is exercised. It is not sufficient to say a government is “sovereign,” because sovereignty is not simply a status — it must be enacted. Investigating questions of sovereignty does not conclude by answering who is sovereign, but also requires understanding if and how power is being used and applied. This is part of the reason why much of the attention raised about Canadian sovereignty is concerned with whether we have adequate support for our claims to Arctic sovereignty.

Conventional understandings of sovereignty within Canada are based on a partial understanding of how state authority developed in Europe. In Canada, we typically think of sovereignty as practised through our constitutional structure — that is, the exercise of power occurs through federalism. Thinking of reconciliation as a diplomatic or inter-national effort challenges this exclusive view of sovereignty as held by settlers. It requires settler institutions to understand how Indigenous nations have developed governance systems and that their interpretation of sovereignty does not reflect European history. A starting point involves examples of political confederacies, such as the Wabanaki or the Haudenosaunee, or wampum agreements, such as the Dish with One Spoon or Two Row Wampum. In these cases, nations come together and form shared spaces — either territorial or political — while still maintaining their own sovereignty. This, for instance, is how the Mi’gmaq and Wolastoqey nations navigate overlapping title claims to the same territory in N.B.

To take meaningful strides toward reconciliation, we need to move away from an exclusive vision of sovereignty. The final reports of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls National Inquiry (MMIWG), the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) and the RCAP offer a different vision of Indigenous-settler relations. First, the TRC understands reconciliation as the creation of possibility for a shared future by “establishing and maintaining a mutually respectful relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples” with the ultimate aim of “coming to terms with events of the past in a manner that overcomes conflict and establishes a respectful and healthy relationship among people, going forward” (TRC, 2015, p. 6). Crucial to this process is the expectation of ongoing relationships between self-determining peoples — an understanding that builds on the RCAP’s 1996 Final Report. These relationships will necessarily be spread across Canada, with multiple and overlapping jurisdictions between peoples. These documents outline reconciliation as a relationship of deciding on shared futures together, not one of a single party dictating to the other.

This, however, is not how settler governments currently practise reconciliation, despite their statements of support for the findings and recommendations of both the RCAP and the TRC reports. Instead, they expect First Nations to fit within federal structures and policies, which ultimately reinforce settler sovereignty. The “mini-municipality” model is a good example, according to which First Nations are to provide services in a similar manner to that of municipalities, with powers delegated from the federal government (Abele & Prince, 2006). Where First Nations seek economic development opportunities, they must often be undertaken in line with provincial environmental assessment processes — such as the Ring of Fire development of mineral deposits in northern Ontario — or in line with provincial returns-on-investment guidelines — such as N.B.’s renegotiation of excise-tax agreements with the Wolastoqey and Mi’gmaq nations. Affirming provincial or federal jurisdiction in cases such as these sustains colonial systems and hierarchical relationships in the present. In this context, reconciliation becomes what Midzain-Gobin and Smith refer to as “reconciliation lite”: a way of absolving Canadian governments for past harms while legitimizing ongoing colonial rule (Midzain-Gobin & Smith, 2020) and supporting Canada’s claims to an exclusive sovereignty.

When Canada uses the constitutional order to claim Indigenous lands and the authority to govern across them, it undermines the possibility of a shared future. Even if First Nations are considered partners, as treaty federalism would suggest (White, 2002), the rules of engagement are set by the settler constitutional order and affirmed by court decisions. Despite Indigenous nations’ clearly articulated expectations that treaties maintain self-determination, their political orders have been domesticated — interpreted as confined within the application of Canadian sovereignty by settler governments (Starblanket, 2019). In these cases, Indigenous-settler relations exist only within the Canadian constitutional order, rather than the Canadian polity needing to truly engage with nations existing in the same space. Instead of looking to Canada’s constitution — which Indigenous nations have not joined despite section 35 affirming their existing rights — our vision is for a relational and inter-national coexistence (Eisenberg, 2022; Wildcat, 2020). In such a system, multiple peoples and nations exercise distinct sovereignty in the same geographic space (Wildcat, 2020, pp. 177-181) and negotiate shared systems where these powers overlap. Our argument for a move toward relationships that are more diplomatic in nature, then, is premised on provincial actors in Canada moving away from current understandings of reconciliation.

Making the Provincial Inter-National

The relationship between the Crown(s) and Indigenous peoples is multifaceted, as is reflected by the differences in provincial approaches to negotiations on land, rights and sovereignty. For reconciliation to be meaningful, it is thus important for Canadian governments to move away from understandings of Indigenous nations as domestic political actors, akin to interest groups within settler states (not unlike municipalities, for example),[5] and instead acknowledge them as international, sovereign actors (Lightfoot & MacDonald, 2020). This move also acknowledges the diversity of skills, knowledges, practices and traditions that Indigenous nations use to interact with different colonial actors, as well as their own histories of diplomacy (King, 2017; Lightfoot & MacDonald, 2017). Similarly, Indigenous peoples regularly engage with international organizations such as the United Nations and other Indigenous nations worldwide (Lightfoot & MacDonald, 2020).

This is to say that Indigenous nations are international actors. Consequently, and reflecting Indigenous nations’ sovereignty, Crown-Indigenous relations should be considered inter-national and practised through the lens of diplomacy. In international relations literature, many scholars have thought of diplomacy outside of building state-to-state relationships (Bedford & Workman, 1997; Beier, 2005, 2009; King, 2017; Lightfoot, 2016; Lightfoot & MacDonald, 2017). Rather, by using different conceptions of the international and a diversity of actors, diplomacy can represent broader constellations of interactions and negotiations. This lens is useful for thinking of the inter-national in terms of the overlapping sovereignties, territories, constitutions, polities and authorities that populate what we call Canada.

A key concept is paradiplomacy, which is useful to our analysis in three ways. First, it allows us to imagine decision-making power as dispersed rather than centralized in a settler government. Second, it allows us to see how Indigenous actors enact their own sovereign power and push back against moves to “domesticate” them as subgroups of Canada. Finally, it helps us see Indigenous legal systems and sovereignty as legitimate, parallel and in relation to each of the provincial Crowns. Turning to a diplomatic lens allows us to (a) assess existing relationships between provinces and Indigenous nations; and (b) discuss government mechanics that can move toward better policy, in which equality between provinces and Indigenous nations becomes possible.

In Canada, paradiplomatic activities are often undertaken by provinces with other countries or other subnational actors. For example, the governors of the New England states and the premiers of the Atlantic Canadian provinces have been meeting regularly since 1973 (Council of Atlantic Premiers [CAP], n.d.) and British Columbia, Washington and Oregon signed the Columbia River Treaty in 1961 (B.C., n.d.-a). Most commonly in Canada, we see such activities play out in provincial engagement in the international realm (Paquin, 2020). Examples include the participation of Quebec and New Brunswick governments in the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie, or Ontario and Quebec’s overseas offices that manage trade, culture and other relations. We believe that it is possible to expand upon these types of efforts when considering Indigenous-Crown relations as inter-national; such that relationships between provinces and Indigenous nations develop based on the precedent of paradiplomacy.

Our goal is to examine how the reality of a profound power disparity and inequality between settler provincial governments and Indigenous nations in Canada, in this case First Nations, can be reduced. Two factors are worth consideration: First, although provinces are co-sovereign in their own domains with their individual capacities to exercise prerogative powers (as established in the Constitution Acts of 1867 and 1982), the federal government reserves the exclusive right to exercise the foreign policy prerogative. How then might provinces manage what are fundamentally nation-to-nation relationships? Our approach begins from the concept of paradiplomacy and is grounded in the theory of multiple Crowns — that is, there is more than one Crown in Canada. This theory reflects the constitutional reality, reaffirmed in the patriation process, in which provinces are co-sovereign and able to sue one another, establish their own honours systems or prevent the transport of alcohol across provincial borders. The assertion of provincial control over so-called Crown lands is the clearest example of this theory in practice. It is not simply a question of two different governments exercising control of lands “belonging” to the same Crown — N.B.’s so-called Crown lands are distinct from so-called Crown lands in Nova Scotia.

To have diplomatic relations that resemble paradiplomacy, the parties must understand with which sovereign entities they are engaging. Historically, Indigenous-settler relations have seen shifts between who represents settlers and Indigenous nations, and especially how that authority is constituted and organized. To take First Nations as an example, the creation of band councils through the Indian Act of 1867 imposed a settler understanding of governance structures on communities. This has resulted in parallel leaders in some places: those elected through the Indian Act system, whose authority is sourced in the Indian Act, and those who are hereditary and/or traditional leaders. As such, the federal government’s interference in First Nations governance structures creates incoherency and complications in the relationship. This is the case in B.C., where the LNG pipeline through the Wet’suwet’en nation’s territory has been approved by the Indian Act-elected band council, but met with steadfast rejection from the hereditary leaders. Despite the federal and provincial governments recognizing the authority of the hereditary chiefs by signing a tripartite Memorandum of Understanding in May 2020 — itself a further recognition of the Delgamuukw decision to grant authority over lands to the hereditary chiefs — both governments continue to act incoherently by upholding the band council’s decision as the authoritative one.

The second factor is section 91 of the Constitution Act of 1867, which places the responsibility for “Indians and lands reserved for Indians” in the jurisdiction of the federal government. The common understanding is that, at the time of Confederation, all relationships that the colonial provinces and imperial authorities had with “Indians” (then only considered to be First Nations) were transferred to the federal government in Ottawa, in effect placing Canadian obligations to treaties and other pre-Confederation responsibilities in the hands of the federal government. However, this relates only to reserve lands, not all lands covered by treaties. Provinces retained control of most other lands. In provinces like N.B., whose own “Indian Act” of 1844 created pre-Confederation reserves, the transfer of authority paved the way for unfettered exploitation and commercial profit of the lands that the province had stolen from the Mi’gmaq, Wolastoqiyik and Peskotomuhkati. The act of Confederation erased N.B.’s own role in removing and displacing Wabanaki peoples from their lands. The provincial government still denies that Wabanaki lands are unceded and unsurrendered.

This reflects how Canadian governments actively create confusion over whether the federal or provincial governments can competently represent the Crown in relations with Indigenous nations. Typically, this is broached within the context of “jurisdiction” flowing from the Canadian constitutional arrangement. Every provincial government maintains a department or executive office dedicated to Indigenous relations or Aboriginal/Indigenous Affairs, which is charged with engagement with First Nations and, in some cases, service delivery. But these governmental bodies are primarily responsible for navigating key, and complicated, intergovernmental and jurisdictional questions: Which level of settler government is responsible for financing public services to Indigenous peoples? Who is responsible for delivering those services? Provinces typically defer questions of Indigenous rights to the federal government, even though the provincial government likely exercises the greatest discretion over whether those rights are respected. For example, in the constitutional division of powers, provinces are responsible for the land, natural resources and waterways within their territorial boundaries. They are equally responsible for health, education and social development, including housing and welfare, as well as the administration of the justice system off-reserve, where most Indigenous peoples — including First Nations — live. In N.B., this amounts to almost 400 government-led or -involved initiatives, not counting ongoing negotiations and litigation, with the 15 First Nations of the Wolastoqey and Mi’gmaq, as well as the Peskotomuhkatiyik. In B.C., cataloguing such initiatives with the more than 150 First Nations in the province is much more complicated, though they likely add up to many hundreds, if not thousands, depending how province-wide agreements are counted. In other words, although provinces may act as if the Indigenous-settler relationship is not their responsibility, they are responsible for the vast majority of government interactions with First Nations, Inuit and Métis.

Distinguishing between the federal and provincial governments’ engagements with Indigenous peoples is therefore vital to understanding the future of the relationship. In questions of Land Back — such as in the Wolastoqey title claim to large parts of the territorial landmass in N.B. — so-called Crown lands are those over which the provincial Crown asserts control, not the federal. Understood through Indigenous sovereignty, the divisions can remain “incoherent” (Starblanket, 2019), with the various provinces stepping in at times when the federal government refuses to, even in jurisdictions of federal authority, and electing not to at others.[6] Showing up only sometimes and without a clear pattern as to why is not good diplomatic practice. How are Indigenous nations meant to read such behaviour, if not as a sign of disinterest as willingness to exert the colonial power to decide? While Canada is not alone in this incoherency (Bell, 2018), the practice creates an inconsistent set of relationships, in which First Nations have to guess why or when each government will engage on particular issues at specific times. As we see below, this makes ongoing and stable relations more difficult, as bi- and multilateral relations require a consistency that provincial incoherency undermines.

Paradiplomatic Relations in an Inter-National “Canada“

Paradiplomacy involves actors that are not traditionally considered states engaging in formal, diplomatic relationships with other actors that are also not traditionally considered states. In expanding it to encompass Crowns and a multiplicity of Indigenous actors, we want to underline that provinces are already paradiplomatic actors. That is, they already have the skills to develop policy that frames relationships from a diplomatic perspective. Engaging these skills in a new policy arena is valuable both for the purpose of moving away from domestication as well as for reconfiguring the nature of Crown-Indigenous relations.

Literature on paradiplomacy in Canada often focuses on Quebec, the clearest actor engaging in its own foreign policies, trade negotiations, multilateral memberships (such as in La Francophonie) and more. Stéphane Paquin also notes that Alberta was present at the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement negotiations and at the Keystone XL pipeline negotiations in Washington, D.C. (Paquin, 2020, p. 56). Other provinces also have international relationships that vary in their formality. Many are with the United States, but others extend elsewhere. Ultimately, paradiplomacy can change the nature of arrangements between provinces and other actors, allowing power to be less centralized while also enabling a consistency in the relationships. Looking to First Nations, the provinces could be more predictable and coherent in maintaining relationships if they did not have the centre (the federal government) to appeal to. This moves away from the exclusive visions of sovereignty perpetuated through strict federalism. Instead, provincial Crowns would develop their own relationships with the Indigenous nations whose lands they occupy. Such forms of diplomatic recognition could fundamentally reshape relationships if carried out in a way that supports collaborative governance and embraces Indigenous sovereignties.

How might we build on paradiplomacy? What might it look like in practice? Key to moving toward a set of diplomatic relationships is decentralizing authority and building new mechanisms through which to practise the relationship. This brings us back to the concept of sovereignty and the need for these mechanisms to operate based on Indigenous peoples’ free, prior and informed consent (FPIC). Current models, even where they are more inclusive or collaborative, maintain unequal dynamics through which provinces often act unilaterally, or use divide-and-rule tactics to pit communities against each other. What is needed if we are to implement relational ways of practising sovereignty? For provinces to not only commit to, but also follow through on, acting only in cases where they are not undermining the decisions of Indigenous nations who remain sovereign. Furthermore, Indigenous nations must be adequately resourced, and their existing protocols must be recognized and respected. If paradiplomatic relations are meant to be collaborative, policy work must be approached from the starting point of respect for unique sovereignties and a credible commitment to not violate those. These parameters (including new mechanisms that shift authority to Indigenous nations, implement FPIC, and provision of adequate resources) are how we can evaluate whether paradiplomatic relations are being established.

To take up the prior example of environmental impact assessments, if projects are to be given provincial licences, they may have to go through assessments based on a First Nation’s own processes and law — perhaps following “reclamation” processes already under way (Pasternak & King, 2019). That is, settler governments must come to the table with an open mind and creative approach to negotiation that puts the preservation and practising of Indigenous sovereignties at the centre of its policy proposals. Moreover, because settler-colonial wealth has been accumulated through Indigenous dispossession (Coulthard, 2014; Pasternak & Metallic, 2021), redistributive policies that ensure adequate resources and support to Indigenous nations (and the land required to develop the economic basis to exercise sovereignty) are a prerequisite for paradiplomatic relationships to be effective.

Building these relationships can help address the “conciliation challenge” (MacDonald, 2019) — that is, how to actually develop a shared future in the face of a colonial relationship. This is a unique way of thinking of an alternative to the flawed concept of reconciliation that often absolves the Canadian settler state of violence and asks “both sides“ to reconcile, effectively removing the inequality of power from the negotiation. This inequality in the present colonial order is of central concern, since the state has used its power to continue implementing processes aimed at dispossessing Indigenous peoples. Such an imbalance cannot be the basis upon which conciliation, as opposed to reconciliation, moves forward (Edmonds, 2016). Conciliation accounts for the power imbalance wherein the settler state has caused harm and it is not the job of Indigenous peoples to accommodate the state as such. Rather, as John Borrows and James Tully remind us, for genuine rapprochement to occur, settler governments and citizens must move past “certain types of ‘recognition’ that place the state or its imperial networks at the centre of social, political and economic affairs” (Borrows & Tully, 2018, p. 5). Alternative forms of recognition, dialogue and, importantly, sovereignty are thus simultaneously possible and necessary.

Provincial Crown-Indigenous Inter-National Relations

To look at the state of Indigenous-provincial relations we want to highlight and contrast the two distinct approaches British Columbia and New Brunswick have taken in their relationships to First Nations. When B.C. passed the UNDRIP in 2019, it opened the possibility of a more inclusive, paradiplomatic relationship with First Nations within its borders; N.B., on the other hand, has explicitly chosen to maintain its exclusive claim to decision-making and effective power over First Nations. As such, the two provinces represent very divergent approaches to building and maintaining relationships with First Nations. Our purpose in contrasting them is to highlight the differences in how such relationships can be built and practised in an era of reconciliation, rather than highlighting them as the two ends of a single continuum along which each other province might be placed.

British Columbia’s inclusive approach

The necessity of a more inclusive approach in B.C. stems in part from the incredibly different history of Indigenous-settler relations as compared to much of the rest of the country: while not unknown, historical treaties cover a relatively small amount of the land that makes up the province today. Furthermore, today’s B.C. expands across the territory of 198 First Nations who speak over 30 languages and make up a number of nations and tribal councils and have also built other political arrangements. This heterogeneity has produced a series of distinct engagements with settlers, where different expectations and relationships govern different areas of the province. It also means that the long process of creating First Nations reserves in the province resulted in hundreds of small reserves, many of which were established directly adjacent to lands claimed by settlers, and now exist both alongside and within municipalities. Rather than a historical curiosity, this points to a distinctly different type of historical relationship between the Crown and First Nations across much of B.C. Further, unlike in N.B. (or indeed much of the rest of Canada), B.C. was largely formed with an explicit intention to assimilate First Nations into the settler body politic. Whereas the imperative to “civilize” remains the same, First Nations intentionally remained present in and around major cities (Edmonds, 2010) rather than being pushed to more remote areas. As a result, First Nations in B.C. were explicitly to be incorporated into settler economies in a more far-reaching way than those elsewhere.

This is important background information that helps explain the structure of relations between First Nations and the provincial government. Indeed, First Nations are involved not only in land management across the province, but also in nearly every industrial and economic development initiative. In many cases, any sort of action or initiative undertaken by the Province[7] impacts the rights and/or title claims of multiple First Nations. As a result, engagement is constant, on nearly every issue, and takes place with many nations’ interests being represented in multiple venues. To co-ordinate action across the province, First Nations have worked continuously — historically and today — to establish what historian Sarah Nickel describes as a form of “unity” (Nickel, 2019). This critical work has often involved building organizations, such as the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs. It, along with the First Nations Summit and the British Columbia Assembly of First Nations, come together under the banner of the First Nations Leadership Council (FNLC), using that body to work with the Province on matters affecting all. As such, while it remains the case that the Province maintains multiple, and sometimes overlapping, relationships with First Nations in any given issue area, there is a co-ordinated effort among First Nations to work together in dealings with it.

This co-ordinated emphasis on First Nations jurisdiction produces quite a bit of friction with the Province, exacerbated by its historical commitment to affirm sole settler authority. Contemporary treaty and land-claims processes have not been as effective as promised at reducing tensions, especially where the government’s inaction and its insistence on the legitimacy of Crown assertions of exclusive sovereignty have forced First Nations to file numerous legal actions in order to have their claims confirmed. Recently, decisions such as Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia at the Supreme Court of Canada, Yahey v. British Columbia at the B.C. Supreme Court and others have found that First Nations have legitimate claims to much of the territory and authority currently claimed by the provincial Crown, putting pressure on the provincial government to change its approach.

In this context, we have seen potentially important shifts in that approach, which we argue constitute an attempt at more inclusive governance — or at least a stated intention toward it. Primary among these changes was the B.C. Legislature’s passage, on November 28, 2019, of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (DRIPA). With this, B.C. became the first jurisdiction in Canada to pass the Declaration into law. Rather than a government-only initiative, DRIPA was developed in collaboration with First Nations leaders in the province, especially the FNLC. This strengthened the Act because the legislation goes much further than simply reading the Declaration into provincial law: DRIPA requires the government to align provincial law, policy and practices with the Declaration; to develop an action plan outlining how this will be achieved; and to produce annual reports on progress, all done “in consultation and cooperation” with Indigenous peoples as outlined in the Act and associated documents. While we do not want to suggest this is a panacea, it does offer a national (and perhaps, international) standard, and federal legislation like the 2021 Bill C-15 includes similar language. DRIPA’s success was always seen as being based on implementation (Lightfoot, 2019), and the years since its passage have been anything but smooth. However, there have been substantive shifts in the Province’s approach to policy-making and orientation toward First Nations self-determination. As we explore below in a comparison with N.B., the implementation holds the promise of a revised vision of confederation in B.C., one inclusive of First Nations self-determination. That is the promise of the DRIPA, but much work remains to be done if that promise is to be realized.

New Brunswick’s exclusive approach

In contrast to B.C., New Brunswick, like the rest of the Maritime region, has obligations under a series of pre-Confederation Peace and Friendship Treaties that were signed from 1725 to 1799 between the Crown and the nations of the Wabanaki Confederacy, notably the Mi’gmaq, Wolastoqey and Peskotomuhkati. The two largest nations in N.B. are the Wolastoqey and Mi’gmaw, which include 15 First Nations spread across the province. Peskotomuhkati communities are also present in the territory along the United States border, in the southwestern part of the province. The Wolastoqiyik and Mi’gmaq have steadily asserted their own rights to the territory: today, 100 per cent of the provincial landmass is subject to active title claims (Urquhart, 2023) and the nations are collaborating over shared governance across areas of overlapping claims (Bamaniya, 2022).

In this context, the question of how to build relations between First Nations and the Province has been unresolved and has lurched between crises since the 1980s.[8] These crises have been met with liberal multicultural policies that treat First Nations as stakeholders and marginalized minorities, instead of as sovereign nations and treaty partners. The salience of this approach’s continuation today was evident when, in November 2021, the provincial government appointed a Commissioner on Systemic Racism to examine all forms of systemic racism, instead of launching a public inquiry into systemic racism against Indigenous peoples in the provincial justice system, as First Nations leaders had demanded. In her final report, the Commissioner refused to recommend a public inquiry and offered no substantive discussion on the racism and violence specific to Wabanaki peoples that highlighted their unique relationship with land and colonial land dispossession in N.B. (Donkin, 2022).

Using commissions and commissioners is a consistent feature of N.B.’s approach to engaging with First Nations peoples and issues. In the aftermath of the federal

Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, the Province commissioned the Task Force on Aboriginal Issues to examine a number of problems (N.B., 1999). Many persist today, and have evolved and, at times, intensified over the more than 20 intervening years. Instances include the Elsipogtog resistance to government efforts to initiate fracking in Mi’gma’gi (Mi’gmaq homelands) and the aftermath of the brutal 2020 murders of Chantel Moore and Rodney Levi by police. Instead of building processes and institutions to be able to work alongside First Nations in the province, the Province has sought to use external commissions. Where this has been impossible, the Province has instead sought to implement issue-specific, service-based partnerships. A prime example is the Premier’s 2021 decision to cancel the tax-sharing agreements with the Wolastoqey and Mi’gmaq nations, which had given them broad licence to invest those funds in their communities as needed, in favour of government-funded initiatives linked to performance metrics.

In addition to the Premier’s involvement in Indigenous relations, there is a Minister for Aboriginal Affairs who is responsible for the Department of Aboriginal Affairs (DAA), a bureaucratic secretariat that has, for most of its history, been housed in different government departments. Importantly, with respect to inter-national relationship building, the DAA does not operate in the spaces where contact between First Nations communities and the Province is most prominent. Instead, those relationships are typically institutionalized through contribution agreements that keep authority and resources in the hands of the Province. Here, the leading actors are the Departments of Health and Social Development (for health care and social services); Education and Early Childhood Development (for education); Natural Resources and Agriculture, Aquaculture and Fisheries (for forestry, farming and fisheries); Justice and Public Safety (for justice and policing); and Finance and Treasury Board (for taxation and other financial matters). As a result, line departments developed their own in-house capacities to manage the relationship with First Nations communities and negotiate any potential implications for inherent and treaty rights. Historically, this left the DAA with little to do. In the words of N.B.’s Task Force on Aboriginal Issues (1999), “In this regard, New Brunswick has nothing to devolve from one central agency to the other departments — the cupboard is bare” (La Forest & Nicholas, 1999).

In 2018, DAA became its own quasi-stand alone department responsible for representing the province’s interests with respect to Wabanaki peoples, nations and files. The department also provides internal government co-ordination services to support consultations and engagement with Indigenous communities. Interestingly, it does not have any mandate to maintain, foster or develop relations with any of the 15 recognized Wolastoqey or Mi’gmaq First Nations in N.B. It appears to function as a clearing house on stakeholder engagement, purportedly specializing in Indigenous issues. In July 2021, Premier Higgs instructed the department to centralize all initiative management between the Province and First Nations (N.B., 2022). Though the DAA is not actively involved in all these engagements, it requires other departments and agencies to report the almost 400 individual activities between the N.B. government and First Nations. Negotiations and litigation are outsourced to external legal counsel.

Given this structure, there is little coherency to the provincial government’s part in Indigenous relations. Rather than a shared future, or enabling the practice of Wakanaki sovereignty, the N.B. government seeks to maintain exclusive forms of power. As such, a formal relationship more readily understood in diplomatic terms — or even those best described through the Peace and Friendship Treaties that govern the interactions between the Crowns in Maritime Canada and First Nations in the region — does not exist. First Nations leaders refuse to work with the existing Minister of DAA (Brown, 2020). This extends today to UNDRIP implementation; Premier Higgs has noted that the Declaration, and its having been passed by the federal government, has no impact at the provincial level (Amador, 2021).

Comparing inclusive and exclusive approaches

Digging into the specific ways that each province has approached policy implementation offers contrasting approaches:

Looking at the two cases side by side, there are clear divergences: while N.B. has largely sought to maintain the status quo from the pre-UNDRIP era, B.C. has not only passed UNDRIP into provincial law, but has been developing further relationship-building processes that include public reporting through reports and documents. Furthermore, the B.C. government has involved the Deputy Minister in the work, all signs that it does not intend to bury the Declaration. In contrast, N.B. does not appear to have made any public progress on understanding the provincial implications of either the Declaration or the federal legislation enshrining the Declaration into Canadian law. Government rhetoric and action can remain distinct, though, and ultimately, we see two key ways in which B.C.’s more inclusive approach to governance still fails to meaningfully shift the underlying relations.

First, there is a lot of talk of engagement, and engagement on absolutely everything. This may, to an extent, represent a positive development. Counterintuitively, however, potential concerns arise. First, there is the potential for engagement fatigue. There are only so many things that specific individuals and organizations can meaningfully engage on before reaching their capacity. Without additional resources — either provided or procured internally — to further develop existing organizations, and create new ones, this is a real concern. In this respect, leaning so heavily on the FNLC might prove to be a problem, though it is good to see that the FNLC is pushing for other organizations to be involved as well. Second, and related to engagement fatigue, meaningful action in the form of shifts in decision-making — both final decisions and, in many cases, the process itself — seems to be taking too long. For First Nations, this can raise the question: Are governments moving forward on decisions by themselves in an exclusive manner?

The stress tests of COVID-19 can offer insights on this front, and forestry, fishing and environmental assessment might offer some illustrations of First Nations communities’ frustration with government moving ahead on its own schedule instead of giving adequate time for consensus development. In N.B., the Province’s refusal to appoint First Nations representatives to environmental impact assessment panels — despite its willingness to name federal government departments and, in some cases, local governments and municipal administrations — is indicative of its unilateral approach. Ultimately there remains a structural problem: governments are at times not willing to do the work that meaningful engagement requires. They retain significantly more capacity to enact policy, itself a form of power insofar as provinces can overwhelm First Nations or simply wait them out. This government inaction is a key barrier to building the shared future, or even nation-to-nation relationship, that governments claim to be seeking. Overcoming such inaction is crucial to successfully implement the Declaration, and in N.B. an unwillingness to act is evident.

B.C. has taken some steps forward: regular meetings occur, and new provincial legislation on child and family services puts authority in the hands of First Nations rather than the Province (CBC News, 2022). However, overshadowing this is the drawing of lines around which issues follow new processes aimed at shared decision-making, and which follow existing processes that centre the Province’s authority. Pipeline development in Wet’suwet’en territory is one example: despite the May 2020 tripartite agreement between the Wet’suwet’en nation and the federal and B.C. governments, the latter is trying to grandfather in the pipeline, arguing that it came before the agreement and so Wet’suwet’en cannot backtrack on development. The B.C. government is also giving more resources to the RCMP, enabling the multiple violent raids that have occurred since DRIPA was passed into law. Related are the ways the B.C. government argues against First Nations rights to land in court, despite public statements to the contrary, and how it only follows through on recognizing rights and titles after courts have found in favour of First Nations.[9] Rather than being “whataboutism,“ these examples highlight questions of power and decision-making: Will the government side with corporate power and the certainty of Provincial jurisdiction, or with the First Nations’ self-determination? Instead of shifting the relationship, the B.C. government appears to continue relying on colonial divisions of power that favour its existing power and settler development in general.

In N.B., the active Wolastoqey title claim appears to present a similar stalemate with respect to reconciliation. The provincial government is adamant that it will do nothing to jeopardize its own case — going so far as to farcically ban civil servants from performing land acknowledgments that recognize the unceded and unsurrendered territories of the Wabanaki peoples. It is hard to envision a scenario in which good relations can be fostered, and self-determination encouraged and supported, when the province adopts such an aggressively litigious posture. Similar to B.C., it does not appear clear that the N.B. government would be willing to entertain the notion of Wabanaki self-determination, at least not until the courts determine the ongoing question of Aboriginal title. In February 2022, the Mi’gmaq nation presented an updated assertion of its title claim, which, though not established through the Canadian legal process, covers similar themes to the Wolastoqey claim: it challenges N.B.’s sovereignty and the provincial Crown’s capacity to exercise control over so-called Crown lands and lands sold to major industrial lumber actors.

Current forms of recognition politics produce a situation in which the settler state retains the power to recognize Indigenous claims to authority or not (Coulthard, 2014; Eisenberg et al., 2014). That is, settler sovereignty remains at the centre of decision-making. Decentring the state, by emphasizing shared decision-making, offers the opportunity to move past hierarchical relationships toward ones reflective of paradiplomacy and rooted in Indigenous governance orders and practices. In our two cases, provincial governments already engage with First Nations, especially on issues involving the Crown’s exercise of control over lands claimed as Crown land. But these negotiations proceed from the basis of exclusive Crown sovereignty, whereas we are proposing that First Nations’ sovereignties be the basis for shared decision-making. Given settler constitutional frameworks, provinces will inevitably remain engaged in the use and management of territory within their jurisdiction. However, by understanding the Crown as a land claim and thus the need for the Crown to engage in paradiplomacy, we can evaluate governance relations according to how effectively they centre Indigenous nations in decision-making and we can formalize “proper and good ways to conduct […] relationships” (Wildcat, 2020, p. 177). This would see decision-making take place not through unilateral choices by provinces, but rather through engagement that proceeds from a base recognition of Indigenous authority. In this case, all parties hold relationships to each other, but also the responsibility to maintain them through “proper and good ways” of engagement. Paradiplomatic processes offer the opportunity to do so. Moreover, they reframe the question, moving away from who has the final say toward how to make decisions together.

Conclusion

Understanding Canada as an inter-national space requires us to shift how we imagine relationships between Indigenous nations and provincial governments. In turn, it requires new ways of practising those relationships. Of course, our ideas are not entirely novel; rather we apply existing concepts to the relationships between Canadian provinces and Indigenous nations. The latter have rich histories of diplomatic relationships between nations prior to and during colonization. One key example comes from the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, which resulted from the bringing together of first five, then six, distinct nations, even while each continues to maintain its own authority and governance traditions (Bedford & Workman, 1997; Belanger, 2007; Monture, 2014). Other examples across the country reflect the interconnections that exist between nations while each remains distinct, such as the trading relationships that led to the construction of Grease Trails across what is today B.C. and into the prairies, and the relationships between the nations of the Wabanaki Confederacy across what are today the Maritime provinces. In some respects, reframing the discussion of our federation in diplomatic terms represents a return to these relationships — and calls on a rich history of Indigenous self-determination.

Further, some treaty relationships between Indigenous nations and the Crown were seen as diplomatic arrangements at the time they were signed (rather than an exchange of land for rights). Some treaties were signed under duress and settler violence, and others were shaped by colonial conditions or violated by settler governments. The Two Row Wampum Belt between the Haudenosaunee and the Dutch Crown — and later agreements with the British Crown, notably the Silver Chain Covenant and the mid-nineteenth-century Peace and Friendship Treaties with the Wabanaki Confederacy — offers a strong case of how two parties can coexist while remaining distinct. Of course, these cases also underline how treaties in Canada vary in form, function and even whether they exist at all. Framing these relationships as diplomatic gives us better insights into their complexity as they were established and practised. It also highlights provincial Crown obligations toward re-building this coexistence in such different corners of Canada — even in a context where both historic and present-day relations differ markedly.

Central to this process is the expectation of ongoing relationships into the future between self-determining peoples — an understanding that builds from the RCAP’s 1996 Final Report. These relationships are to be spread across Canada, with multiple and overlapping jurisdictions between peoples that will not be easily untangled. We do not expect these relationships to always be positive; there will be disagreements, naturally. However, reconciliation in the way that we have described it in this study offers a pathway to building a future together. Instead of relying on a colonial politics of recognition to enable Indigenous self-determination, as current governance models do, reconciliation is rooted in the practices that accompany self-determination. As we have seen above, neither the inclusionary approach taken by B.C. nor the exclusionary one taken by N.B. meaningfully changes the underlying relations. Both affirm what Moreton-Robinson (2015) refers to as “white possession” and what Mackey (2016) refers to as the “fantasy of entitlement” — the assumption of sole and unitary sovereignty of the Canadian Crown.

How might we move past this into an inter-national future? One useful proposal stems from RCAP, and it involves the issuing of a new Royal Proclamation (or new Royal Proclamations in affected provinces). While the original from 1763 was intended to recognize the rights and title of Indigenous nations — what we would understand as sovereignty — settler governments have conveniently ignored its meaning. Instead, they have assumed their right to act unilaterally on behalf of the Crown and, in doing so, have not upheld the principle of the honour of the Crown. Issuing a new Royal Proclamation, one that recognizes Indigenous sovereignty and directs governments to work from that understanding, can be a first step to bring back that honour. As the RCAP noted in Volume 5, renewing relationships after violence has been typical historical practice both among Indigenous nations and settlers. A renewed Royal Proclamation would allow us to achieve that.

This would also have the benefit of aligning with our obligations under UNDRIP. Regardless of the N.B. government’s stance on the Declaration, it is international law and, as a result, Canadian courts can draw on it. Indeed, they are beginning to. More than just issuing a new Proclamation, we as settlers must develop governance processes that treat Indigenous nations as equals and that operate in accordance with Indigenous law. Achieving this will require developing political and economic capacity, and political and legal orders among Indigenous nations, which requires both human and financial resources. Initiatives such as B.C.’s recent revenue-sharing agreement with First Nations, which takes a proportion of funds from gaming revenues across the province and gives it to First Nations for their own projects, are a good start. More stable funding that is used at the discretion of Indigenous communities for self-determined projects is needed.

Ultimately, this comes down to political will. Courts have been making clear for decades that settler fantasies of entitlement, when implemented unilaterally by governments, create unlawful intrusions on Indigenous sovereignty and jurisdiction. While the RCAP Final Report and its attendant recommendations may not be top of mind in Victoria or Fredericton — or Edmonton, Toronto or even Ottawa for that matter — it offered a concrete blueprint to achieving some measure of a shared future. That governments have deliberately continued with unilateral action illustrates an allegiance to the white possessiveness that denies the possibility of such a future. This will have to change if inter-national relations are to be affirmed and practised. Not only are such relations a step forward themselves, insofar as they better reflect the sovereignty of Indigenous peoples, but by enabling their decision-making power, they will also benefit everyone, settler and Indigenous communities alike.

[1] We are being intentional with our references to First Nations here given the relations in our two cases (British Columbia and New Brunswick). The principles may be useful in some cases for thinking about Métis or Inuit relations with provinces; however, the particularities of these cases (i.e., Inuit land claims and the historic non-recognition of the Métis) complicate questions and require their own analyses.

[2] It is useful here to think of the Canadian government claiming an authority to act over and above already existing Indigenous nations who have their own governance traditions and histories. In such cases, prior occupancy would see primacy rest with Indigenous nations (Coburn & Moore, 2022).

[3] We use Westphalian system here to reference the international system of sovereign states, which has traditionally been said to begin with the 1648 Peace of Westphalia. Not all polities neatly map on to existing state borders. Indeed, as evidenced by Indigenous nations, there exist many more communities that maintain their own political identity, and governance systems, than the individual sovereign states. In the Canadian context, provinces such as Québec may also maintain their own claims to such a status.

[4] Sheryl Lightfoot has written about how the Haudenosaunee developed and continue to use their own passports, with the Republic of Ireland in 2022 accepting Haudenosaunee passports for their national lacrosse team’s entry for matches (Lightfoot, 2021).

[5] This political move has a long history within settler colonial states. Jeff Corntassel writes of how the Canadian state (and British imperial government) asserted that Chief Deskaheh’s representations to the League of Nations in 1923-24 were inappropriate, as Haudenosaunee concerns were a domestic matter, not an international one (Corntassel, 2008). Likewise, Sheryl R. Lightfoot notes how leaders in Australia, Canada and New Zealand have all claimed that Indigenous communities are a domestic concern in the face of organizing around international Indigenous rights (Lightfoot, 2016).

[6] Here we are working from Starblanket’s (2019) theorization of a “politics of incoherency” vis-à-vis settler colonization in Canada. Writing about Canada’s interpretation of the numbered treaties across the Prairies, Starblanket works from King and Pasternak’s (2018, p. 18) analysis of treaties as “international land-sharing agreements.” However, as Starblanket argues, Canada has reinterpreted these treaties as land-cessation devices, orienting them toward racial and cultural meanings and uprooting their application from the context of Indigenous legal order. This move allows for various interpretations by the government, each useful to maintaining settler-colonial authority.

[7] In the analysis that follows, we are capitalizing Province when referring to the provincial government acting on behalf, and exercising the powers, of the provincial Crown. This is to clarify the distinctions between the province as a territorial area, and the administrative entity responsible for certain powers of the Crown.

[8] Especially notable in this time are the Crisis in the Forest over wood harvesting rights and the Burnt Church Crisis over fisheries following the Marshall decision in 1999 (N.B., 1999; Obomsawin, 2022).

[9] The most recent example is the decision won by Blueberry River First Nation (Yahey v. British Columbia), which then led to the provincial government signing agreements with First Nations from Treaty 8. By contrast, the Nuchatlaht have had to take the province to court to assert their title, even after DRIPA was passed.

Abele, F., & Prince, M. J. (2006). Four pathways to Aboriginal self-government in Canada. American Review of Canadian Studies, 36(4), 568-595. https://doi.org/10.1080/02722010609481408.

Agnew, J. (1994). The territorial trap: The geographical assumptions of international relations theory. Review of International Political Economy, 1(1), 53-80.

Amador, M. (2021, June 28). UNDRIP bill reaches end of its journey. The Eastern Door. https://easterndoor.com/2021/06/28/undrip-bill-reaches-end-of-its-journey/.

Bamaniya, P. (2022, August 22). Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqiyik sign declaration to protect Big Salmon River. CBC News New Brunswick. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswick/indigenous-led-protection-big-salmon-river-watershed-1.6558264.

Bedford, D., & Workman, T. (1997). The Great Law of Peace: Alternative inter-nation(al) practices and the Iroquoian Confederacy. Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, 22(1), 87-111.

Beier, J. M. (2005). International relations in uncommon places: Indigeneity, cosmology, and the limits of international theory. Palgrave Macmillan.

Beier, J. M. (2009). Indigenous diplomacies. Palgrave Macmillan.

Belanger, Y. D. (2007). The six nations of grand river territory’s: Attempts at renewing international political relationships, 1921–1924. Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, 13(3), 29–43.

Bell, A. (2018). A flawed treaty partner: The New Zealand state, local government and the politics of recognition. In D. Howard-Wagner, M. Bargh, & I. Altamirano-Jiménez (Eds.), The neoliberal state, recognition and indigenous rights: New paternalism to new imaginings, vol. 40 (pp. 77-92). Australian National University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv5cgbkm.

Borrows, J., & Tully, J. (2018). Introduction. In M. Asch, J. Borrows, & J. Tully (Eds.), Resurgence and reconciliation: Indigenous-settler relations and earth teachings (pp. 3-25). University of Toronto Press.

British Columbia, Government of (B.C.). (n.d.-a). Columbia River Treaty. https://engage.gov.bc.ca/columbiarivertreaty/.

British Columbia, Government of (B.C.). (n.d.-b). BC First Nations Gaming Revenue Sharing Limited Partnership. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/governments/indigenous-people/first-nation-gaming-revenue-sharing.

British Columbia, Government of (B.C.). (2022, March 30). Declaration Act action plan. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/governments/indigenous-people/new-relationship/united-nations-declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples/implementation.

Brown, S. (2020, December 23). Working group’s success depends on N.B. mending relationship with Indigenous leaders: Opposition. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/7539189/success-working-group-n-b-government-relationship-indigenous-leaders-opposition/.

CBC News. (2022, November 25). New legislation gives B.C. Indigenous communities control of their own child welfare system. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/b-c-indigenous-communites-granted-power-over-child-welfare-1.6664683.

Coburn, V., & Moore, M. (2022). Occupancy, land rights and the Algonquin Anishinaabeg. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 55(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423921000810.

Corntassel, J. (2008). Toward sustainable self-determination: Rethinking the contemporary Indigenous-rights discourse. Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, 33(1), 105-132. https://doi.org/10.1177/030437540803300106.

Council of Atlantic Premiers (CAP). (n.d.). New England Governors and Eastern Canadian Premiers (NEG-ECP). https://cap-cpma.ca/negecp/.

Coulthard, G. S. (2014). Red skin, white masks: Rejecting the colonial politics of recognition. University of Minnesota Press.

Donkin, K. (2022, December 16). Systemic racism report calls for N.B. task force, not the inquiry sought by First Nations. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswick/systemic-racism-commissioner-final-report-1.6688382.

Dunn, A., Hon. (2021, May 28). The Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples: Evidence. https://sencanada.ca/en/Content/Sen/Committee/432/APPA/06ev-55242-e.

Edmonds, P. (2010). Urbanizing frontiers: Indigenous peoples and settlers in 19th-century Pacific Rim cities. University of British Columbia Press.

Edmonds, P. (2016). Settler colonialism and (re)conciliation: Frontier violence, affective performances, and imaginative refoundings. Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series. Palgrave Macmillan.

Eisenberg, A. (2022). Decolonizing authority: The conflict on Wet’suwet’en territory. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 55(1), 40-58. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423921000858.

Eisenberg, A., Webber, J. H. A., Coulthard, G., & Boisselle, A. (Eds.). (2015). Recognition versus self-determination: Dilemmas of emancipatory politics. University of British Columbia Press.

King, H. (2017, July 31). The erasure of Indigenous thought in foreign policy. OpenCanada. https://www.opencanada.org/features/erasure-indigenous-thought-foreign-policy/.

King, H., & Pasternak, S. (2018). Canada’s emerging indigenous rights framework: A critical analysis. Yellowhead Institute. https://yellowheadinstitute.org/rightsframework/

La Forest, G., & Nicholas, G. (1999). Assessment and recommendations — The role of the provincial government. In Report on the Task Force on Aboriginal Issues. https://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/aboriginal_affairs/publications/content/task_force.html#anchor65625.

Lavoie, J. (2022, March 16). Nuchatlaht take fight for heavily logged territory to B.C. Supreme Court. Here’s what you need to know. The Narwhal. https://thenarwhal.ca/nuchatlaht-indigenous-title-undrip/.

Lightfoot, S. R. (2016). Global Indigenous politics: A subtle revolution. Routledge.

Lightfoot, S. R. (2019, November 13). B.C. takes historic steps towards the rights of Indigenous peoples, but the hard work is yet to come. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/b-c-takes-historic-steps-towards-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples-but-the-hard-work-is-yet-to-come-126311.

Lightfoot, S. R. (2021). Decolonizing self-determination: Haudenosaunee passports and negotiated sovereignty. European Journal of International Relations, 27(4), 971-994. https://doi.org/10.1177/13540661211024713.

Lightfoot, S. R., & MacDonald, D. B. (2017). Treaty relations between Indigenous peoples: Advancing global understandings of self-determination. New Diversities, 19(2), 25-39.

Lightfoot, S. R., & MacDonald, D. B. (2020, March 12). The UN as Both Foe and Friend to Indigenous Peoples and Self-Determination. E-International Relations (blog). https://www.e-ir.info/2020/03/12/the-un-as-both-foe-and-friend-to-indigenous-peoples-and-self-determination/.

MacDonald, D. B. (2019). The sleeping giant awakens: Genocide, Indian residential schools, and the challenge of conciliation. University of Toronto Press.

Mackey, E. (2016). Unsettled expectations: Uncertainty, land and settler decolonization. Fernwood Publishing.

Midzain-Gobin, L., & Smith, H. A. (2020). Debunking the myth of Canada as a non-colonial power. American Review of Canadian Studies, 50(4), 479-497. https://doi.org/10.1080/02722011.2020.1849329.

Monture, R. (2014). We share our matters (Teionkwakhashion tsi niionkwariho:ten): two centuries of writing and resistance at Six Nations of the Grand River. University of Manitoba Press.

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2015). The white possessive: Property, power, and indigenous sovereignty. University of Minnesota Press.

New Brunswick, Government of (N.B.). (1999). Report of the Task Force on Aboriginal Issues. https://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/aboriginal_affairs/publications/content/task_force.html.

New Brunswick, Government of (N.B.). (2022). Aboriginal Affairs Annual Report 2021-2022. Province of New Brunswick. https://www2.gnb.ca/content/dam/gnb/Departments/aas-saa/pdf/AnnualReport-RapportAnnuel/annual-report-2021-2022.pdf.

Nickel, S. A. (2019). Assembling unity: Indigenous politics, gender, and the Union of BC Indian Chiefs. University of British Columbia Press.

Obomsawin, A. (Director). (2002). Is the Crown at war with us? [Film]. National Film Board of Canada. https://www.nfb.ca/film/is_the_crown_at_war_with_us/.

Paquin, S. (2020). Paradiplomacy. In T. Balzacq, F. Charillon, & F. Ramel (Eds.), Global diplomacy: An introduction to theory and practice (pp. 49-61). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28786-3_4.

Pasternak, S., & King, H. (2019, March). Land back: A Yellowhead Institute red paper. Yellowhead Institute. https://redpaper.yellowheadinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/red-paper-report-final.pdf.

Pasternak, S., & Metallic, N. W. (2021, May). Cash back: A Yellowhead Institute red paper. Yellowhead Institute. https://cashback.yellowheadinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Cash-Back-A-Yellowhead-Institute-Red-Paper.pdf.

Poitras, J. (2023, January 9). Wolastoqey chief predicts “chaotic” expiry to tax agreements. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswick/wolastoqey-chief-predicts-chaotic-expiry-tax-agreements-1.6707987.

Simmons, M. (2023, January 25). Blueberry River First Nations beat B.C. in court. Now everything’s changing. The Narwhal. https://thenarwhal.ca/blueberry-river-treaty-8-agreements/.

Starblanket, G. (2019). The numbered treaties and the politics of incoherency. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 52(3), 443-459. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423919000027.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC). (2015). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada.

Urquhart, M. (2023, February 15). Mi’kmaw First Nations expand Aboriginal title claim to include almost all of N.B. CBC News New Brunswick. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/new-brunswick/mi-kmaq-aboriginal-title-land-claim-1.6749561.

White, G. (2002). Treaty federalism in Northern Canada: Aboriginal-government land claims boards. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 32(3), 89-114. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubjof.a004961.

Wildcat, M. (2020). Replacing exclusive sovereignty with a relational sovereignty. Borderlands, 19(2), 172-184. https://doi.org/10.21307/borderlands-2020-014.

Wood, P. B., & Rossiter, D. A. (2020). The geography of the Crown: Reflections on Mikisew Cree and Williams Lake. The Supreme Court Law Review, 94(2d), 187-205.

ABOUT THIS PAPER

Liam Midzain-Gobin is a settler scholar whose work focuses on settler colonialism, Indigenous governance and decolonization. He is an assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at Brock University.

Caroline Dunton is a Research Associate at the Centre for International Policy Studies at the University of Ottawa. She holds a PhD from the University of Ottawa.

Robert Tay-Burroughs is the former senior adviser to New Brunswick’s commissioner on systemic racism. His PhD research at the University of New Brunswick (Saint John) focuses on placemaking, settler colonialism, and the role of the Crown’s representatives in reconciliation.

To cite this document:

Midzain-Gobin, L., Dunton, C., & Tay-Burroughs, R. (2023). Reimagining Canada as Inter-National: Understanding First Nations-Provincial Relationships. IRPP Insight 47. Institute for Research on Public Policy.

The opinions expressed in this paper are those of these authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IRPP or its Board of Directors.

IRPP Insight is a refereed series that is published irregularly throughout the year. It provides commentary on timely topics in public policy by experts in the field. Each publication is subject to rigorous internal and external peer review for academic soundness and policy relevance.

If you have questions about our publications, please contact irpp@irpp.org. If you would like to subscribe to our newsletter, IRPP News, please go to our website, at irpp.org.

Cover photo: Shutterstock.com

ISSN 2291-7748 (Online)

Une nouvelle étude de l’IRPP trace une voie vers la réconciliation par le recadrage des relations entre les Autochtones et les provinces

Montréal – Les relations entre les peuples autochtones et les allochtones sont souvent réduites aux interactions entre deux groupes : le Canada et les peuples autochtones. Qui plus est, les interactions entre le gouvernement fédéral et les Autochtones sont généralement les plus médiatisées, alors que celles avec les provinces sont pourtant beaucoup plus fréquentes et d’une plus grande ampleur. Afin de résoudre ces problèmes et d’améliorer la voie vers la réconciliation, une nouvelle étude du Centre d’excellence sur la fédération canadienne de l’Institut de recherche en politiques publiques (IRPP) met en lumière l’importance des interactions entre les provinces et les peuples autochtones et appelle à une nouvelle perspective fondée sur la diplomatie.

Dans cette étude, les coauteurs Liam Midzain-Gobin, Caroline Dunton et Robert Tay-Burroughs réimaginent les échanges entre les nations autochtones et les gouvernements provinciaux comme des relations internationales qui devraient être considérées comme diplomatiques en soi. Ce changement de perspective permet de reconnaître que chaque acteur apporte son propre système de gouvernance et sa souveraineté à la table des négociations, en plus de rappeler que la collaboration et l’inclusion sont indispensables à l’obtention de résultats positifs pour les communautés autochtones.

« Notre objectif est d’examiner la profonde disparité de pouvoir entre les gouvernements provinciaux et les nations autochtones au Canada afin d’arriver à la réduire. Pour aller plus loin dans la réconciliation, nous devons reconnaître la riche complexité et la diversité historique des nombreuses nations et des provinces, chacune ayant ses propres systèmes de gouvernance et traditions » explique Liam Midzain-Gobin, auteur principal de l’étude.

Pour démontrer le potentiel de cette approche diplomatique, l’étude se penche sur le Nouveau-Brunswick et la Colombie-Britannique, en mettant en contraste des stratégies de gouvernance qui aboutissent à des résultats très différents dans les relations autochtones-provinciales. Alors que la Colombie-Britannique a fait preuve d’une approche inclusive et a déclaré son désir d’impliquer les peuples autochtones dans la prise de décision, le Nouveau-Brunswick s’est montré réticent à suivre une voie similaire, ce qui a limité la coopération et tendu les relations avec les Premières Nations de la province.

En fin de compte, l’étude appelle toutes les parties concernées à collaborer à l’élaboration de processus de gouvernance qui traitent les nations autochtones comme des partenaires égaux. Des investissements soutenus, une volonté politique et la valorisation de l’autodétermination autochtone sont essentiels pour continuer à progresser.

« En adoptant un point de vue international et des pratiques plus proches de la diplomatie, plutôt que de traiter les Premières Nations comme de simples parties prenantes ou des acteurs internes au sein du Canada, nous pouvons jeter les bases d’un avenir commun ancré dans une gouvernance collaborative qui respecte la souveraineté autochtone. Un investissement soutenu, une volonté politique et le renforcement de l’autodétermination autochtone sont essentiels pour progresser vers la réconciliation », conclut Charles Breton, directeur du Centre d’excellence sur la fédération canadienne de l’IRPP.