Coming into Its Own? Canada’s Council of the Federation, 2003-16

- Depuis sa création en 2003, le Conseil de la fédération est devenu une institution intergouvernementale engagée, qui privilégie de plus en plus les moyens d’améliorer la collaboration entre provinces et territoires.

- Dans certains domaines, comme l’établissement des prix des produits pharmaceutiques, le Conseil a élaboré d’intéressantes politiques alternatives.

- Le Conseil a été moins efficace dans des domaines où les provinces et territoires ont des intérêts divergents, par exemple en matière de lutte contre les changements climatiques.

Interprovincial relations in Canada have a long history, starting with the first meeting of the premiers in 1887, convened by Quebec Premier Honoré -Mercier.1 At the instigation of another Quebec premier, Jean Lesage, meetings of premiers became more formalized in 1960 with the creation of the Annual Premiers’ Conference (APC). For 40 years, the APC was a low-key but regular venue for interprovincial relations. In 2003, the APC became the Council of the Federation (COF), which now largely coordinates provincial-territorial (P/T) relations.

Initially, a number of authors offered lukewarm predictions for the COF.2 However, Christopher Dunn’s recent assessment is that the council “came into its own” during Stephen Harper’s term as prime minister and offered “useful policy alternatives.”3 Scarce attention has been paid to the COF since its creation,4 so it is worth assessing in some detail its role and how it has affected intergovernmental relations. Which topics have attracted premiers’ attention in the past 13 years, and what have been the results? In short, what impact has the COF had on Canadian federalism?

Based on a review of COF documents from 2003 to 2016 and a recent in-depth study of P/T relations,5 this paper provides an overview of COF activity since the council’s founding. It also examines two specific areas of P/T action, the Health Care Innovation Working Group (HCIWG) and climate change, in order to get a better sense of the COF’s role and potential in developing policy alternatives. On some issues, the premiers have led, but on others coordinating action has been a challenge. Nevertheless, the council has become an active intergovernmental body with a wide scope of action, a well-developed network of intergovernmental officials, and an increased focus on how the P/T governments can work together effectively.

Establishment of the Council of the Federation

A group of Swiss federalism experts has described intergovernmental relations as “‘the drop of oil’ that smooths the operation of the federal system.”6 Intergovernmental institutions and processes are often categorized as vertical (where the federal government is involved) or horizontal (with no federal government participation). A recent in-depth study of intergovernmental relations in federal systems identified increased horizontal interaction as an emerging trend and gave as examples the COF and the Council for the Australian Federation.7

The COF’s predecessor, the APC, was a well-established horizontal body. Its summer conferences offered premiers a chance to get to know each other, often over a game of golf. Gradually, provincial and (after 1982) territorial premiers came to see the APC as a mechanism for coordinating responses to the federal government. The organization became more structured and more focused on the provinces’ relationships with Ottawa.8 Commenting on these changes in 1991, former Ontario premier Bob Rae observed that the “institution had evolved. Fam-ilies [of the premiers] still came, but there was a formal agenda, and part of the meeting was televised. Extensive discussions were held among staff long before the meeting about the wording of the post-conference communiqué.”9

In 1994, Quebec Premier Daniel Johnson suggested formalizing the APC. The presence of a Parti Québécois government from 1994 to 2003 halted such discussions, but the idea was not abandoned by the Quebec Liberal Party, which -released a report — the Pelletier report — in 2001.10 The report recommended the creation of a quasiconstitutional council of the federation that would include the federal government, would vote using a system of vetoes (for the federal government, British Columbia, the prairie provinces, Ontario, Quebec and the Atlantic provinces) and would complement the Senate. The Pelletier report even suggested that “[w]e could at a later date try to give [the council] a constitutional character if it proved opportune.”11

After taking office, in 2003, Quebec Premier Jean Charest immediately set about creating the COF. The result was less ambitious than what the Pelletier report proposed. For example, there are no regional vetoes. The COF is nevertheless the most formal venue for top-level intergovernmental relations in Canada. It is a modestly institutionalized, consensus-based P/T body with the following objectives:

- strengthening interprovincial-territorial cooperation, forging closer ties between the members and contributing to the evolution of the Canadian federation

- exercising leadership on national issues of importance to provinces and territories and in improving federal-provincial-territorial relations

- promoting relations between governments based on respect for the Constitution and recognition of the diversity within the federation

- working with the greatest respect for transparency and better communication with Canadians12

Rather than creating something radically different, the COF borrowed from the APC. However, contrary to the recommendations of the Pelletier report, the fed-eral government did not become a member of the COF. The council’s founding agreement notes that part of the COF’s mandate is to “analyse actions or measures of the federal government that in the opinion of the members have a major impact on provinces and territories.”13 It specifies that decisions are to be made by consensus, which mirrors the practice of most intergovernmental bodies in Canada (there are a few exceptions, such as the rule for changes to the Canada Pension Plan).14

The contrast between the language of the founding agreement and the relatively modest changes that ensued is telling. The preamble states, “It is important to participate in the evolution of the federation and to demonstrate [the premiers’] commitment to leadership through institutional innovation,”15 but the hesitation to agree to fundamental changes to the existing P/T framework suggests the premiers are not keen on a major transformation. Scholars have noted this hesitancy. Ian Peach, for example, titled his 2004 backgrounder “Half-Full at Best.”16 But, as nearly 15 years have passed since its founding, it is worth reassessing the COF, its activities and its impact on the federation.

Overview of the Council of the Federation’s Activities since 2004

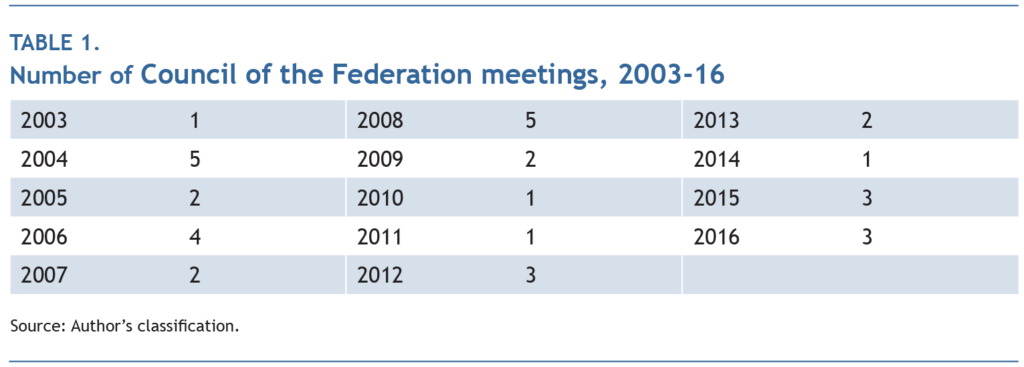

Rather than meeting once a year like the APC, the COF meets at least twice annually. Since 2004, it has met at least twice in all but three years (see table 1). In two years, there were five meetings. The greater number of meetings in 2004 can be explained by the premiers’ initial enthusiasm; the greater number in 2008 reflects heightened intergovernmental activity during the financial crisis that began that year.

From 2006 to 2015, the COF’s focus on coordinating P/T action toward Ottawa was complicated by Stephen Harper’s preference for bilateral (rather than multilateral) relations with the premiers. As one official commented in 2011: “[Harper’s approach] does make some of the work that was originally envisaged by COF a little bit more difficult. Consequently, COF has adapted to the present operating environment.”17

The central COF event is a multiday summer meeting. However, whereas the APC was more a social forum at which premiers could get to know each other, COF meetings are more focused on work. Indeed, it is common at a winter meeting to announce work to be reported on at the summer meeting or to present updates on issues discussed at the previous summer meeting. A number of provincial officials refer to a cycle in the period leading up to COF meetings.18 At any given moment, the COF’s work extends to more than a dozen ad hoc working groups created to cover specific issues.

Activities by Sector

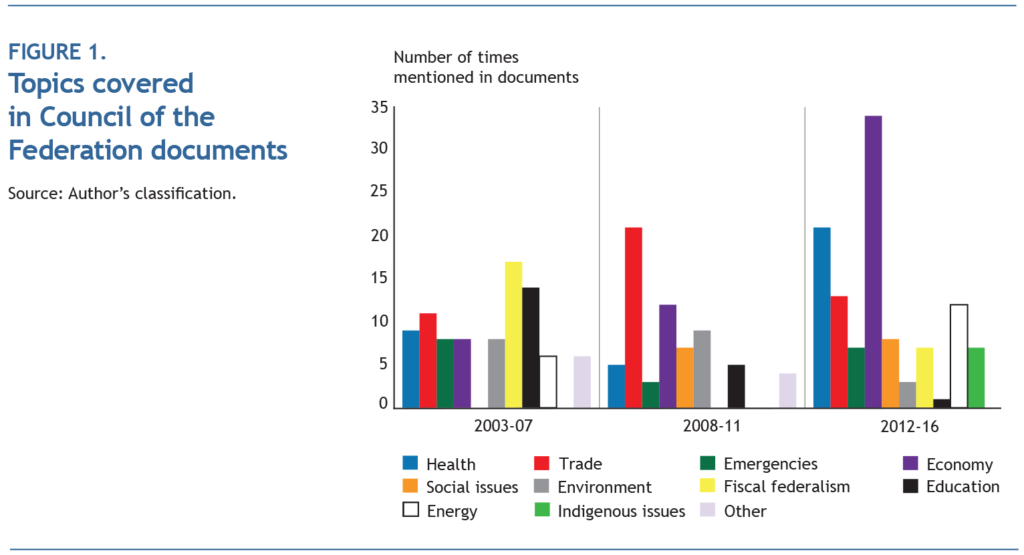

In my analysis of COF documents from 2003 through to the December 2016 meeting, I identified 11 major topics: health, trade, emergencies, the economy, social issues, the environment, fiscal federalism, education, energy, Indigenous issues and other. If a topic was mentioned in a communiqué, it was scored 1; if it was the subject of its own dedicated communiqué, it was scored 2; if it was the subject of a dedicated report, it was scored 3. The results are reported in figure 1.

Health

Because health care is primarily a provincial jurisdiction, it has been a frequent topic of discussion. Two major issues stand out. In the period following its creation, the COF primarily focused on negotiations over the 2004 health accord, a set of 10-year intergovernmental health-funding agreements signed between P/T governments and the federal Liberal government of Paul Martin. The accord increased federal health transfers by 6 percent a year and was considered to be an early victory for the COF, demonstrating how a united front could pressure the prime minister.19 From 2007 to 2010, health was not mentioned in COF documents. Since 2010, the issue has again been discussed, and it was the second most frequently addressed topic in the 2012-16 period, in large part due to the creation of the Health Care Innovation Working Group (discussed later).

Discussions on health from 2010 to 2015 mostly centred on coordinating P/T action in the face of the federal government’s unwillingness to engage in multilateral discussions. The tone of intergovernmental relations changed following the election of the Justin Trudeau government in October 2015, and a call for renewed federal-provincial agreements was on the agenda of the 2016 summer meeting. However, federal health minister Jane Philpott’s vow to maintain the 3 percent a year increase in health funding angered the premiers. An October 2016 meeting of the federal-provincial-territorial (F/P/T) health ministers ended with the premiers unanimously rejecting the federal position.20 This unanimity did not last, and shortly after the December 2016 F/P/T meeting of health and finance ministers, New Brunswick accepted a side agreement with the federal government, which provides for additional funding for targeted areas. Over the months since the F/P/T meeting, all of the P/T governments except Manitoba have accepted similar side agreements.21

Trade

No year has passed without mention of internal and international trade. Between 2008 and 2011, there was a sharp increase in discussions on trade for two main reasons. The first was the involvement of the provinces in the negotiations on the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) with the European Union.22 The second and larger component was the movement to strengthen the Agreement on Internal Trade (AIT). Signed in 1994, the AIT is the main means by which interprovincial trade in Canada has been harmonized. One of the first topics discussed in 2004 was renewing the AIT.23 As Loleen Berdahl argues, in the past decade, work on the file has largely been driven by provincial governments, though not always through the COF.24

According to officials involved,25 frustration over a lack of progress in the COF led Alberta and British Columbia to create their own agreement, the 2006 Trade, Investment and Labour Mobility Agreement (TILMA), renamed the New West Partnership following the inclusion of Saskatchewan, in 2010. Manitoba also joined, in early 2017. Discussions of the AIT took on greater prominence only after the creation of the TILMA, which is reflected in figure 1. Significantly, the 2016 COF summer meeting saw the premiers unveil an agreement in principle on a new canadian free trade agreement (CFTA).26 Unlike the AIT, the CFTA will be comprehensive and based on a “negative listing” approach, in which government measures are subject to free trade provisions unless specifically excluded. Although the list of exclusions has yet to be released, the premiers have vowed to work with the federal government on implementing the agreement and specifically on tackling barriers to interprovincial alcohol sales, a perennial trade irritant.27

Economy

Economic issues have been an ongoing topic, and they predominate in COF documents between 2012 and 2016. This category groups together several disparate issues, from temporary foreign workers to retirement income to spending on infrastructure. In general, the COF has taken two approaches on economic matters. The first is to deal with matters of pressing concern, such as unilateral federal funding decisions. The second is to demonstrate the positive role of the provinces and territories in economic development, for example by having premiers lead a COF trade mission to China (without the Prime Minister) in 2014.28

During the Harper era, provinces and territories often found themselves collectively reacting to federal initiatives through the COF. The issue of labour market training is an apt example. In 2013, the federal government announced that it was planning to reassert its role in labour market training (which it had gradually ceded in the late 1990s). Provinces and territories voiced their displeasure through the COF and succeeded in preventing the proposed changes.29 The same tactic was used less successfully by the provinces with regard to federal changes to the temporary foreign workers program.30 Although the COF has sometimes been critical of the federal government on economic issues, it did serve as a forum to coordinate F/P/T responses to the 2008 financial crisis — for instance, by fast-tracking approval of shovel-ready infrastructure projects.31 The years following the financial crisis were among the few in which the Harper government had good multilat-eral relations with the premiers.

Social issues

Social issues, including immigration, housing, support for families and support for disabilities, receive periodic mention in COF documents but less so than energy or health. Since 2008, housing has been mentioned five times in COF communiqués, but it was never the subject of its own communiqué or COF study. Interestingly, other prominent social issues such as social assistance have not been mentioned in COF documents. It should be noted that the COF is not the only (or the most important) forum for intergovernmental discussion: issues such as social assistance are routinely discussed at meetings of the ministers responsible for social services. But if COF documents indicate which issues attract attention, they also indicate which ones do not.

Environment

Environmental issues, especially climate change, have been discussed relatively often at COF meetings. Between 2003 and 2007, there were discussions about environmental assessment and the green economy. The COF also made recommendations on the issue of water stewardship and in 2010 adopted a water charter, which sets out principles for interjurisdictional coordination on water conservation. Since 2007, most discussions of the environment have centred on climate change (discussed later).

Fiscal federalism

One of the central purposes of the COF is to coordinate relations with the federal government, so fiscal relations are a natural part of the COF’s agenda. The Conservative government’s election in 2006 complicated the premiers’ initial plans: Stephen Harper avoided First Ministers’ Meetings, preferring bilateral meetings or delegation to ministerial councils. That said, it is rare for a COF summer meeting to pass without the provinces and territories calling for certain action by the federal government, and the most prominent issue is fiscal transfers. Whether in the context of infrastructure spending, health transfers, equalization or simply general discussions of fiscal arrangements, it is common for the COF to request that the federal government increase or stabilize fiscal transfers.

Extensive debate about the fiscal imbalance and equalization took place between 2004 and 2006.32 Following the success of the 2004 health accord, the premiers turned to equalization, producing a report titled Reconciling the Irreconcilable. But, unlike with health, consensus proved more difficult to achieve and agreement among the provinces foundered.

Education

Communiqués related to education, which is under exclusive provincial jurisdiction, deal mainly with two subjects: literacy (including an annual literacy award); and post-secondary education (PSE) and skills training. Discussion of education is usually linked to economic issues. For example, a 2011 report on international students focused primarily on the economic benefits of attracting such students to Canada and of making Canada a more competitive player in the international education market.33

Energy

Like equalization, energy is often a source of disagreement. In recent years, discord between Alberta and the other provinces over the oil sands has been prominent.34 In general, discussions of energy have attempted to reconcile the economic importance of fossil fuels (centred in Alberta and Saskatchewan) with the need to favour renewable, environmentally friendly types of energy.

Since 2007, premiers have produced multiple iterations of a COF energy strategy that attempted to balance economic and environmental concerns. The 2007 COF energy strategy, for instance, notes: “As the world has turned its attention to the critical issue of climate change, it is increasingly important to develop, transport, and use energy resources in an environmentally responsible manner.”35 At the instigation of Alberta Premier Alison Redford, a 2013 report reaffirmed the P/T commitment to developing Canada’s energy resources while mitigating the effects of climate change and greenhouse gases.36 The 2015 COF energy strategy notes among its principles “Addressing climate change and moving toward a lower carbon economy.”37 In spite of this agreement on broad principles, ongoing and occasionally very public disagreements over the practicalities of pipeline development demonstrate the difficulty of achieving consensus and results on energy issues.38

Indigenous issues

Although Indigenous matters are, constitutionally, the preserve of the federal government, P/T governments also have an obvious interest. As Martin Papillon notes: “The level of provincial engagement with Aboriginal peoples has grown exponentially in the past decade.”39 This provincial engagement has taken place mainly through -discussions over the crisis of Aboriginal children in care, and in recent years, there have also been commitments to implement the recommendations of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.40 It should also be noted that since 2004, premiers have held a pre-COF meeting with the leaders of the five national Aboriginal organizations.41 Despite these moves, relations between the council and national Aboriginal leaders are still relatively low-key, in part because some Aboriginal leaders are wary of too much engagement with provincial governments, fearing they will be perceived as letting the federal government “off the hook.”42

Emergencies

The council has also been used by premiers as a forum for discussing pressing public safety issues, including disease (H1N1), illegal drugs (crystal meth) or natural disasters (flooding).43 These kinds of emergencies have been a minor but consistent focus of attention since the creation of the COF, and the council has been used as a means to coordinate action, prepare for future emergencies and request additional funding from the federal government.

One of the major purposes of the COF is to coordinate P/T action toward the federal government. Even when the federal government avoided multilateral relations, premiers frequently called for more funding or more stable transfers. This approach has been evident in many areas, including health, emergencies and the economy. Despite considerable collaboration following the 2008 financial crisis, several issues have since involved clashing federal and P/T interests over funding, including pensions and infrastructure.44 On the other major purpose — allowing P/T governments to lead in their own areas of jurisdiction — the record is less evident. Premiers may come to agreements, but it is not clear whether these lead to actual change.

To get a better sense of the work and impacts of the COF, it is useful to explore two specific examples of issues to which the COF has devoted particular attention: health care and climate change.

Health Care Innovation Working Group

On forming the government in 2006, Stephen Harper promised to honour the Martin government’s 2004 health accord.45 With the 2014 expiry approaching, in 2011, provincial governments began anticipating negotiations with the federal government on a renewed health-funding agreement. In preparation, a COF meeting on health funding was scheduled for January 2012.46 It therefore came as a surprise when, at a meeting of F/P/T finance ministers in December 2011, Conservative finance minister Jim Flaherty announced with no warning that the federal -government would maintain a 6 percent annual health-funding increase until March 31, 2017. After that, the health transfer would increase each year by the greater of nominal GDP growth or 3 percent. In reaction, Quebec Premier Jean Charest criticized the federal government for having “side-swiped” the provinces.47

Flaherty’s funding announcement drove the provinces to demonstrate that they could achieve improvements to the health care system without the federal gov-ernment’s involvement.48 This led to the creation of the HCIWG at the January 2012 meeting. Chaired by the premiers of Saskatchewan and Prince Edward Island and composed of all P/T health ministers, the HCIWG initially had a limited one-year mandate. It was asked to produce recommendations in three areas for the 2012 summer meeting: clinical practice guidelines, team-based models and human resource management. The report was released in July 2012. Satisfied that the process demonstrated the ability of the provinces and territories to work together quickly and effectively, in July 2013, the premiers extended the mandate of the HCIWG by three years and tasked it with developing recommendations in three new areas: pharmaceuticals, appropriateness of care and senior care.49

Health stakeholder groups such as the Canadian Nurses Association and the Can-adian Medical Association played an important role in the HCIWG. Particularly on the question of clinical practice guidelines, stakeholder groups were involved to a degree they considered unprecedented.50 Over time, however, disagreements over the goals of the process led to less participation by stakeholders. Although stakeholders were eager to see the working group’s recommendations implemented, after the first year, on the instruction of the premiers, intergovernmental officials moved on to new issues. As one official noted, the HCIWG process had devolved into a standard “government relations exercise.”51 Nevertheless, it was a novel demonstration that positive, fruitful working relationships between P/T officials and health stakeholder groups were possible. One stakeholder representative, who was otherwise disappointed in the results, reflected that “I can say it was a pleasure, and the people from the government, the civil servants, were delightful and very competent, very committed.”52

The most prominent work of the HCIWG related to pharmaceutical pricing, a concern that predated the working group: COF discussions about saving money through the bulk purchase of prescription drugs began in 2010 with the creation of the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (pCPA).53 Bulk pharmaceutical purchasing is an area where premiers can point to significant results. The COF has reported that the work of the pCPA (and consequently of the HCIWG) has saved governments $712 million.54 Following the 2015 federal election, the Lib-eral government announced its interest in joining the pCPA, which it did in early 2016.55 A January 2017 report found that Canadians pay the second-highest prices in the world for some prescription drugs, prompting federal health minister Jane Philpott to promise action.56 This may lead to further intergovernmental cooperation on prescription drug purchases in the future.

At the 2016 COF summer meeting, the premiers released a report on the achiev-ements of the working group.57 The report has a positive tone and presents a number of examples of how the HCIWG has improved health outcomes in diff-erent jurisdictions. On the issue of appropriate care, for example, the 2016 report points to conferences in 2014 and 2015 that allowed practitioners to share best practices with each other and with governments. Overall, the report makes clear that the HCIWG has been used successfully as a forum to share information. But on implementation, the report provides a good deal of leeway, noting that “provinces and territories intend to implement the measures and recommendations outlined in the report as they deem appropriate to their health care system.”58 This latitude is realistic and necessary, given the provinces’ and territories’ reluctance to give up their autonomy, whether they are dealing with the federal government or with each other.

The HCIWG has been a good-news story for the premiers, particularly when it comes to pharmaceutical pricing (the $712 million noted earlier is frequently touted in HCIWG documents).59 The premiers’ ability to work together to save significant taxpayer dollars is one of the best examples of offering useful policy alternatives. Although the relative lack of information on pan-Canadian adoption of HCIWG recommendations is not surprising, in a federal system that privileges jurisdictional autonomy the HCIWG demonstrates a capacity for P/T leadership and (particularly with the pCPA) results.

Climate Change

Discussions of the environment in Canada cannot avoid jurisdictional issues. Simply put, the Fathers of Confederation did not anticipate a need for environmental protection (the concept essentially did not exist) and did not include it in the Constitution. As a result, the environment is under shared jurisdiction. By virtue of their power over natural resources, local matters and municipalities, provincial governments exercise a good deal of control over environmental matters. The federal government maintains jurisdiction over navigable waters, and through its power over criminal law also has the ability to regulate environmental pollution. It can use its taxation powers for environmental purposes and its emergency powers (the “peace, order, and good government” clause) to justify environmental protection measures. Indeed, some critics suggest that the federal government has not gone far enough in protecting the environment.60

The Mulroney government began to expand the federal role in environmental protection in the late 1980s and early 1990s (for which Mulroney was recog-nized as being the “greenest” prime minister).61 Although the Chrétien Liberal government signed the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, it was not ratified by Parliament until 2002, and little action resulted. For its part, the Harper government did not consider climate change to be a priority and did little between 2006 and 2015.

The main body for coordinating environmental policy is the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME). Unlike many other intergovernmental bodies, the CCME is relatively well institutionalized, with a fairly large and well-funded secretariat.62 Nevertheless, the work of the CCME has been circumscribed by the provinces’ drive to maintain autonomy and federal reluctance to impose policy on the provinces and territories.

In the absence of strong federal leadership, provinces have tended to move slowly and disparately. Although Nancy Olewiler concludes that Canada has avoided a “race to the bottom” in terms of environmental regulation, she argues that for decades Canada has been “stuck at the status quo.”63 The federal government sets modest environmental targets, but provincial governments seldom exceed and occasionally miss them.

By 2010, scientific consensus on human-caused climate change had solidified, and in 2015, every major party platform included at least a cursory discussion of the issue.64 But if there is a consensus on the existence of climate change, the provinces have not yet agreed on what should be done about it.

Since the first reference to climate change, in 2007, the issue has been mentioned eight times in COF documents. In 2007, the premiers released a report chronicling the efforts of the provinces and territories, which was followed up in 2008 by an update on implementation.65 Although other environmental issues, such as water stewardship, were addressed, climate change as a stand-alone issue was not mentioned again until 2014. Since 2014, the COF has increasingly focused on carbon pricing as a way of addressing climate change, although such discussions have frequently occurred in the context of negotiations over energy transmission, as seen earlier.

Snoddon and VanNinjatten note wide discrepancies among the provinces on addressing climate change, and observe that “[e]xisting interprovincial coordination mechanisms have so far failed to reconcile provincial differences.”66 The 2016 Conference Board of Canada report gives Canada a D grade on the envir-onment and notes that the highest-performing Canadian jurisdiction (Ontario) is still ranked 11th of 26 comparator regions.67 Conference Board vice-president Louis Thériault argues that “[i]n addition to having a long way to go, Canada does not have a map to get there.”68

The election of the Trudeau government in October 2015 brought a major change to the intergovernmental dynamic.69 One of the new government’s first actions was to attend the twenty-first annual Conference of the Parties in Paris, along with most of the premiers (all were invited). A First Ministers’ Meeting in March 2016 led to a broad agreement to put a price on carbon emissions, but with few specifics. Working groups were directed to report by October 2016 on specific ways of implementing a pan-Canadian framework for clean growth and addressing climate change.70 To the surprise of many, that month, Trudeau announced the federal government would give the provinces until 2018 to implement either a cap-and-trade system or a carbon tax, in line with federal minimum standards; if a province did not, the federal government would levy a carbon tax on it.71 This move was in marked contrast to previously limited federal action, and it engendered strong opposition, most notably from Saskatchewan Premier Brad Wall, who promised to challenge the move in court.72

The difficulty in coordinating P/T positions on climate change is predictable. A major challenge is that the jurisdictions have different economic interests. Sask-atchewan and Alberta have historically been wary of any move that might neg-atively impact their fossil-fuel-based resource sector. Quebec and Manitoba are keen to have their hydro developments recognized. Still others, notably in Atlantic Canada, are hesitant to close existing coal facilities. (Nova Scotia has recently reopened some coal mines.) 73 Discussions on climate change cannot be separated from those on energy, which quickly leads to regional disagreement over pipelines — one of the most contentious intergovernmental issues.

In sum, coordinating intergovernmental policy to combat climate change in Can-ada is difficult. Constitutionally, jurisdiction is divided, and although the federal government may be able to force certain action, it has historically been reluctant to do so. Only in the past year has the federal government begun making serious moves. Individual provincial governments are also constrained by their economic and political situations. Based as it is on consensus, the COF has proven unable to overcome these challenges. It will be interesting to see what role it plays as implementation of the federal initiative proceeds.

In the key policy areas of health and environment, we see two different approaches and two different outcomes. The agreements on bulk purchasing of pharmaceuticals provide one of the most substantial results of P/T collaboration in recent memory. This success in a field where all P/T governments face huge budgetary pressures contrasts with the low level of P/T coordination on climate change. In the latter case, differing economic interests based on the uneven regional distribution of oil and natural gas, among other factors, have made it difficult for governments to agree on anything beyond vague commitments to enhanced environmental protection.

Assessing the Council of the Federation

How should we assess the contribution of the Council of the Federation? Early commentaries were skeptical, wondering if it was simply “old wine in a new bottle.”74 A textbook on Canadian federalism claimed that the COF was simply the Annual Premiers’ Conference by another name.75 Dunn’s recent assessment (quoted at the outset) is more positive. How one evaluates the COF, however, depends on the measure one used.

The most obvious way of assessing the COF is to ask whether it has accomplished what the founding agreement intended: coordinating P/T action toward the federal government and identifying areas where premiers can exercise leadership in their own areas of jurisdiction. On the first criterion, certain examples demonstrate the usefulness of P/T unity. The 2004 health accord is the most obvious, but the successful effort to stop unilateral federal changes to labour market training also dem-onstrates that the council can force a reconsideration of federal policy. However, recent tense negotiations on health funding illustrate the enduring difficulties involved in coordinating P/T action toward Ottawa.

On the COF’s ability to coordinate leadership in areas of P/T jurisdiction, the record is somewhat more positive, if uneven. On certain issues (climate change and energy, in particular), disagreement among the P/T governments has meant the premiers have not advanced a cohesive position. The COF works by consensus, which poses significant challenges for collective action. This feature of federalism is also present in F/P/T relations, but the federal government can sometimes use fiscal levers to entice provincial governments to shift their positions (as the recent example of health-funding bilateral agreements demonstrates). On their own, provincial governments often have neither the interest nor the power to force each other to take certain actions or implement particular solutions.

On other issues the COF’s record is better. The pCPA, the HCIWG and the water charter show that joint action is possible when provinces and territories cooperate. The progress on internal trade is also instructive: in spite of the persistence of certain barriers, the COF has been an impetus for a more robust Agreement on Internal Trade.

The COF can also be assessed at an operational level. Even if the COF is not a radical departure from the APC, the presence of a steering committee, a secretariat and funding has made it more substantial than the APC, and the secretariat has been useful in providing ongoing administrative support and corporate memory.76 More importantly, the COF has helped create closer links among provincial and territorial governments. As one provincial official observed: “It has helped precipitate increased communications between provinces and territories…which is an incredibly significant thing, given the broad range of jurisdiction, sectors and items that are within provincial jurisdiction.”77 This increased communication is important, as well-developed informal relations are a key component of intergovernmental relations in Canada.78

Conclusion

The COF’s record is mixed: some issues have seen major accomplishments, while there has been little progress on others. In large part this can be attributed to the inherent limits of P/T relations. The unanimity rule is central to Canadian federalism, in part because the provincial governments zealously guard their autonomy. The dynamics of the COF thus tend to favour consensus, and few communiqués have been issued without all the premiers being on board.79

Nor should we expect the COF’s relationship with the federal government to change greatly. Although Prime Minister Trudeau has revived multilateral meetings with the premiers, fiscal realities (as well as profound disagreements over matters such as a carbon tax and health care transfers) mean that F/P/T relations in certain key areas are likely to remain tense. In consequence, the COF will probably continue to play the role it did during the Harper era: presenting a united front against federal funding decisions while moving forward with P/T coordination where possible.

Assessing the 40-year history of the Annual Premiers’ Conference, Peter Meekison wrote, in 2002, that it was founded as a “meeting to address common interprovincial concerns. Over time it became evident that common concerns had less to do with interprovincial issues and more to do with federal-provincial issues.”80 Today’s Council of the Federation is a quite different institution. It addresses a wider range of issues, is more formal and has forged stronger ties among P/T governments. More importantly, its focus extends beyond relations with the federal government. For these reasons, it is indeed fair to say that the COF has “come into its own.”

I am grateful for the support of Leslie Seidle and the editorial team at the IRPP in preparing this article, as well as that of the civil servants and health stakeholders who participated in my research on the Health Care Innovation Working Group and the Council of the Federation. I also wish to acknowledge the financial support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and the Government of Ontario.

- A. Roy, The Québec City Conferences from 1864 to 1989 (Quebec: Commission de la capitale nationale du Québec, 1999).

- D. Brown, ed., Constructive and Co-operative Federalism? A Series of Commentaries on the Council of the Federation (Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy; Kingston, ON: Institute of Intergovernmental Relations, Queen’s University, 2003); see also J. Leclair, “Jane Austen and the Council of the Federation,” Constitutional Forum/Forum constitutionnel 15, no. 2 (2006): 51-61; and I. Peach, “Half-Full at Best: Challenges to the Council of the Federation,” C.D. Howe Institute Backgrounder 84 (Toronto: C.D. Howe Institute, 2004).

- C. Dunn, Harper without Jeers, Trudeau without Cheers: Assessing 10 Years of Intergovernmental Relations, IRPP Insight 8 (September 2016), (Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy, 2016), 18.

- But see E. Collins, “Alternative Routes: Intergovernmental Relations in Canada and Australia,” Canadian Public Administration 58, no. 4 (2015): 591-604; and N. Bolleyer, Intergovernmental Cooperation: Rational Choice in Federal Systems and Beyond (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

- Collins, “Alternative Routes”; E. Collins, “Why Can’t We Be Friends? Informal Relations, Public Policy, and Federalism in Canada” (PhD diss., Carleton University, 2016).

- A. Koller, D. Thürer, B. Dafflon, B. Ehrenzeller, T. Pfisterer, and B. Waldmann, Principles of Federalism: Guidelines for Good Federal Practices — A Swiss Contribution (Zurich and St. Gallen: Dilke Verlag, 2012), 55.

- J. Poirier and C. Saunders, “Conclusion: The Comparative Experiences of Intergovernmental Relations in Federal Systems,” in Intergovernmental Relations in Federal Systems: Comparative Structures and Dynamics, ed. J. Poirier and C. Saunders (Don Mills, ON: Oxford University Press, 2015).

- J.P. Meekison, “The Annual Premiers’ Conference: Forging a Common Front,” in Canada: The State of the Federation 2002 — Reconsidering the Institutions of Canadian Federalism, ed. J.P. Meekison, H. Telford, and H. Lazar (Kingston, ON: Institute of Intergovernmental Relations, Queen’s University, 2002), 141-82.

- B. Rae, “Some Personal Reflections on the Council of the Federation,” in Constructive and Co-operative Federalism? A Series of Commentaries on the Council of the Federation, ed. D. Brown (Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy; Kingston, ON: Institute of Intergovernmental Relations, Queen’s University, 2003), 2.

- B. Pelletier, Un projet pour le Québec: Affirmation, autonomie et leadership (Québec: Parti Libéral du Québec, October 2001).

- Pelletier, Un projet, 105 (translated by the author).

- Council of the Federation (COF), “Founding Agreement” (Ottawa: COF, 2003), 2.

- COF, “Founding Agreement,” 3.

- K. Banting, “The Three Federalisms: Social Policy and Intergovernmental -Decision-Making,” in Canadian Federalism: Performance, Effectiveness, and Legitimacy, ed. H. Bakvis and G. Skogstad (Don Mills, ON: Oxford University Press, 2009).

- COF, “Founding Agreement,” 1.

- Peach, “Half-Full at Best.”

- Collins, “Alternative Routes,” 598.

- Collins, “Why Can’t We Be Friends?”

- H. Bakvis, G. Baier, and D. Brown, Contested Federalism: Certainty and Ambiguity in the Canadian Federation (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 2009).

- K. Harris and P. Zimonjic, “Health Ministers Wrap Tense Talks with No Agreement on Federal Health Funding,” CBC News, October 18, 2016, https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/canada-health-funding-philpott-provincial-ministers-1.3810576.

- Canadian Press, “Ottawa, Quebec Reach Deal on Health Funding,” CTV News, March 10, 2017, https://montreal.ctvnews.ca/ottawa-quebec-reach-deal-on-health-funding-1.3319605.

- See C.J. Kukucha, Provincial/Territorial Governments and the Negotiation of International Trade Agreements, IRPP Insight 10 (October 2016), (Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy).

- Council of the Federation, “The Council of the Federation Takes Action to Improve Trade in Canada” (Vancouver: COF, February 24, 2004).

- L. Berdahl, “(Sub)national Economic Union: Institutions, Ideas, and Internal Trade Policy in Canada,” Publius 43, no. 2 (2013): 275-96.

- Berdahl, “(Sub)national Economic Union,” 284.

- Council of the Federation, “Premiers Strike an Agreement in Principle on Internal Trade” (Whitehorse, YT: COF, July 22, 2016).

- COF, “Premiers Strike an Agreement.”

- R. Benzie, “Premiers to Promote Trade in China — without Harper,” Toronto Star, September 2, 2014, https://www.thestar.com/news/queenspark/2014/09/02/premiers_to_promote_trade_in_china_without_harper.html.

- M. Mendelson and N. Zon, The Training Wheels Are Off: A Closer Look at the Canada Job Grant (Ottawa: Caledon Institute of Social Policy; Toronto: Mowat Centre, School of Public Policy and Governance, University of Toronto, June 2013); Council of the Federation, “Premiers Are Committed to Effective Skills Training and Labour Market Programs” (Toronto: COF, June 18, 2013); Dunn, Harper without Jeers.

- COF, “Skilled Workforce” (Charlottetown: COF, August 29, 2014).

- COF, “Council of the Federation Reiterates Its Confidence in the Economy and the Financial System of Canada” (Montreal: COF, October 20, 2008); Dunn, Harper without Jeers.

- D. Béland and A. Lecours, Canada’s Equalization Policy in Comparative Perspective, IRPP Insight 9 (September 2016), (Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy).

- COF, Bringing Education in Canada to the World, Bringing the World to Canada (Ottawa: COF, June 2011).

- K. Howlett, D. Walton, and S. McCarthy, “McGuinty–Redford War of Words Keeps Simmering,” Globe and Mail, February 29, 2012.

- COF, A Shared Vision for Energy in Canada (Ottawa: COF, August 2007), 2.

- COF, Canadian Energy Strategy: Progress Report to the Council of the Federation (Ottawa: COF, July 2013).

- COF, Canadian Energy Strategy (Ottawa: COF, July 2015), 12.

- C. Hall, “Premiers Conference Could See Clash over Pipelines and Emissions,” CBC News, July 16, 2015, https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/premiers-conference-could-see-clash-over-pipelines-and-emissions-1.3154166.

- M. Papillon, “Introduction: The Promises and Pitfalls of Aboriginal Multilevel Governance,” in Canada: State of the Federation 2013 — Aboriginal Multilevel Governance, ed. M. Papillon and A. Juneau (Kingston: Institute of Intergovernmental Relations, Queen’s University, 2016), 21.

- Council of the Federation, Aboriginal Children in Care (Ottawa: COF, July 2015); Council of the Federation, “Canada’s Premiers Affirm Commitment to Action in Response to Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report” (St. John’s: COF, July 16, 2015).

- The Assembly of First Nations, Métis National Council, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, Native Women’s Association of Canada and Congress of Aboriginal Peoples.

- Papillon, “Introduction: The Promises and Pitfalls.”

- Council of the Federation, “Provinces and Territories Make H1N1 Preparations a Priority” (Regina: COF, August 6, 2009); Council of the Federation, “Communiqué” (Banff, AB: COF, August 12, 2005); Council of the Federation, “Premiers Support National Disaster Mitigation Funding Program” (Vancouver: COF, July 22, 2011).

- Council of the Federation, “Premiers Discuss Issues of Importance to Canadians” (St. John’s: COF, July 17, 2015); Council of the Federation, “Supporting Infrastructure for Job Creation and Economic Growth” (Charlottetown: COF, August 28, 2014).

- Conservative Party of Canada (CPC), Stand Up for Canada (Ottawa: CPC, 2006).

- Council of the Federation, “Council of the Federation Tackles Health Sustainability in Preparation for Discussions with the Federal Government” (Vancouver: COF, July 22, 2011).

- M. Fitzpatrick, “Premiers Join Forces on Health Innovation Group,” CBC News, January 17, 2012, https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/premiers-join-forces-on-health-innovation-group-1.1134517.

- Collins, “Why Can’t We Be Friends?”

- Council of the Federation, “Canada’s Provinces and Territories Realize Real Savings in Healthcare through Collaboration,” (Niagara-on-the-Lake, ON: COF, July 26, 2013).

- Collins, “Why Can’t We Be Friends?”

- Collins, “Why Can’t We Be Friends?”

- Collins, “Why Can’t We Be Friends?”

- Council of the Federation, “Premiers Protecting Canada’s Health Care Systems” (Winnipeg: COF, August 6, 2010).

- Council of the Federation, Leadership in Health Care: Report to Canada’s Premiers on the Achievements of the Health Care Innovation Working Group (Ottawa: COF, July 2016).

- E. Church, “Ottawa Seeks to Join Provinces to Cut Cost of Prescription Drugs,” Globe and Mail (January 17, 2016), https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/ottawa-seeks-to-join-provinces-to-cut-cost-of-drug-purchases/article28235296/; Council of the Federation, “The pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance” (Ottawa: COF, February 2016), https://www.pmprovincesterritoires.ca/en/initiatives/358-pan-canadian-pharmaceutical-alliance.

- T. Sawa and L. Ellenwood, “Health Minister Vows to Save Canadians ‘Billions’ on Drug Prices,” CBC News, January 13, 2017, https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/health-minister-jane-philpott-drug-prices-1.3932254.

- COF, Leadership in Health Care.

- Council of the Federation, From Innovation to Action: The First Report of the Health Care Innovation Working Group (Ottawa: COF, July 2012), 6.

- But see R.F. Beall, J.W. Nickerson, and A. Attaran, “Pan-Canadian Overpricing of Medicines: A 6-Country Study of Cost Control for Generic Medicines,” Open Medicine 8, no. 4 (2014): e130-5.

- K. Harrison, Passing the Buck: Federalism and Canadian Environmental Policy (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1996). See also N.J. Chalifour, “Climate Federalism: Parliament’s Ample Constitutional Authority to Regulate GHG Emissions,” Working Paper 2016-18 (Ottawa: University of Ottawa, Faculty of Law, 2016), https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2775370; and I. Weibust, Green Leviathan: The Case for a Federal Role in Environmental Policy (Surrey, UK: Ashgate, 2009).

- “Mulroney Honoured for Environmental Record,” CBC News, April 20, 2006, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/mulroney-honoured-for-environmental-record-1.616580.

- Bolleyer, Intergovernmental Cooperation.

- N. Olewiler, “Environmental Policy in Canada: Harmonized at the Bottom?” in Racing to the Bottom? Provincial Interdependence in the Canadian Federation, ed. K. Harrison (Vancouver: UBC Press), 114.

- J. Cook, D. Nuccitelli, S.A. Green, M. Richardson, B. Winkler, R. Painting, R. Way, P. Jacobs, and A. Skuce, “Quantifying the Consensus on Anthropogenic Global Warming in the Scientific Literature,” Environmental Research Letters 8, no. 2 (2013): 1-7; K. Grandia, “Canada Election 2015: Where Do the Parties Stand on Climate Change?” (Victoria, BC: DeSmog Canada, October 6, 2015), https://www.desmog.ca/2015/10/06/canada-election-2015-where-do-parties-stand-climate-change.

- Council of the Federation, Climate Change: Leading Practices by Provincial and Territorial Governments in Canada (Ottawa: COF, August 2007); Council of the Federation, Climate Change: Fulfilling Council of the Federation Commitments (Quebec City: COF, July 18, 2008).

- T. Snoddon and D. VanNijnatten,Carbon Pricing and Intergovernmental Relations in Canada, IRPP Insight 12 (November 2016), (Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy).

- Conference Board of Canada, “‘D’ Grade for Canada on New Environment Report Card,” news release (Ottawa: Conference Board of Canada, April 21, 2016), https://www.conferenceboard.ca/press/newsrelease/16-04-21/%E2%80%9Cd%E2%80%9D_grade_for_canada_on_new_environment_report_card.aspx.

- L. Thériault, “Canada’s Climate Change Goals Need a Roadmap for Action” (Ottawa: Conference Board of Canada, July 14, 2016), https://www.conferenceboard.ca/commentaries/energy-enviro/16-07-14/canada_s_climate_change_goals_need_a_roadmap_for_action.aspx.

- Dunn, Harper without Jeers.

- Prime Minister’s Office (PMO), “Communiqué of Canada’s First Ministers” (Ottawa: PMO, March 3, 2016), pm.gc.ca/eng/news/2016/03/03/communique-canadas-first-ministers

- Snoddon and VanNijnatten, Carbon Pricing.

- A. Minsky, “Saskatchewan Premier Brad Wall Willing to Take Carbon Fight to Supreme Court,” Global News (October 9, 2016), https://globalnews.ca/news/2990532/premier-wall-willing-to-take-carbon-fight-to-supreme-court.

- “Donkin Coal Mine in Cape Breton Begins Hiring,” CBC News (June 5, 2015),

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/donkin-coal-mine-in-cape-breton-begins-hiring-1.3102064. - H. Lazar, “Managing Interdependencies in the Canadian Federation: Lessons from the Social Union Framework Agreement,” in Brown, Constructive and Co-operative Federalism?, 1.

- Bakvis, Baier, and Brown, Contested Federalism, 108.

- Collins, “Alternative Routes,” 591.

- E. Collins, “Alternate Routes: The Dynamic of Intergovernmental Relations in Canada and Australia,” (master’s thesis, University of Manitoba, 2011), 88-9.

- Collins, “Why Can’t We Be Friends”; see also G. Inwood, C. Johns, and P. O’Reilly, “Formal and Informal Dimensions of Intergovernmental Administrative Relations in Canada,” Canadian Public Administration 50, no. 1 (2007): 21-41; and S. Dupré, “Reflections on the Workability of Executive Federalism in Canada,” in Collected Research of the Royal Commission on the Economic Union and Development Prospects for Canada, vol. 63, Intergovernmental Relations, ed. R. Simeon (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1985).

- Council of the Federation, “Strengthening International Trade and Relationships” (Winnipeg: COF, August 6, 2010); Council of the Federation, “Premiers Guide Development of Canada’s Energy Resources” (Halifax: COF, July 27, 2012).

- Meekison, “Annual Premiers’ Conference,” 171.

Emmet Collins is an adjunct professor of political studies at the University of Manitoba. A recent graduate of Carleton University’s PhD program in political science, in his research he focuses on federalism and intergovernmental relations.

IRPP Insight is an occasional publication consisting of concise policy analyses or critiques on timely topics by experts in the field. This publication is part of the Canada’s Changing Federal Community research program under the direction of F. Leslie Seidle. All publications are available on our website at irpp.org. If you have questions about our publications, please contact irpp@irpp.org.

To cite this study: Emmet Collins, Coming into Its Own? Canada’s Council of the Federation, 2003-16. IRPP Insight 15 (March 2017). Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy.

The opinions expressed in this study are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the IRPP or its Board of Directors.

For media inquiries, please contact Shirley Cardenas (514) 787-0737 or scardenas@irpp.org.

Copyright belongs to the IRPP.

To order or request permission to reprint, contact the IRPP at irpp@irpp.org

Date of publication: March 2017

ISSN 2291-7748 (Online)

ISBN 978-0-88645-365-7 (Online)

Le Conseil de la fédération a favorisé le rapprochement des gouvernements provinciaux et territoriaux

Montréal – Depuis sa création en 2003, le Conseil de la fédération (CDF) est devenu une institution intergouvernementale engagée qui favorise la collaboration entre provinces et territoires, selon une nouvelle publication de l’Institut de recherche en politiques publiques.

Le CDF est aujourd’hui une institution fort différente de celle qu’il a remplacée, à savoir la Conférence annuelle des premiers ministres, qui avait présidé pendant 40 ans aux relations interprovinciales avec une discrète régularité, observe Emmet Collins, professeur auxiliaire d’études politiques à l’Université du Manitoba. Bénéficiant d’un secrétariat, d’un comité directeur et d’un financement soutenu, il joue un rôle plus important et a effectivement contribué au rapprochement des gouvernements provinciaux et territoriaux.

À l’examen de documents du CDF produits entre 2003 et 2016, Collins retrace ses principales activités dans un ensemble de secteurs. Il dresse un bilan mitigé de sa capacité de coordination dans les domaines de compétence provinciale et territoriale : il y a eu beaucoup de progrès par rapport à certaines questions, nettement moins à l’égard d’autres. « Dans quelques domaines comme l’établissement des prix des produits pharmaceutiques, le CDF a élaboré d’intéressantes politiques alternatives. Il a été moins efficace dans des domaines où les provinces et territoires ont des intérêts divergents, par exemple en matière de lutte contre les changements climatiques. »

Même si le CDF maintiendra vraisemblablement un front uni face aux décisions d’Ottawa en matière de paiements de transfert, son action déborde largement le cadre des relations avec le gouvernement fédéral pour englober un vaste éventail de questions, conclut l’auteur. Pour lui, « le Conseil de la fédération a désormais acquis sa pleine légitimité ».

On peut télécharger la publication Coming into Its Own? Canada’s Council of the Federation, 2003-16, d’Emmet Collins, sur le site de l’Institut (irpp.org/fr).

-30-

L’Institut de recherche en politiques publiques est un organisme canadien indépendant, bilingue et sans but lucratif, basé à Montréal. Pour être tenu au courant de ses activités, veuillez-vous abonner à son infolettre.

Renseignements : Shirley Cardenas tél. : 514 594-6877 scardenas@irpp.org